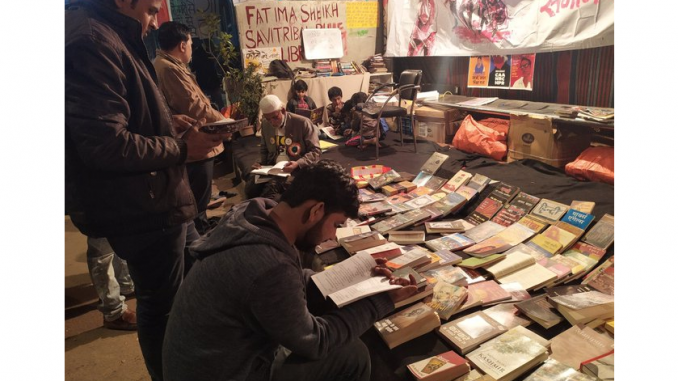

Fatima Sheikh Savitri Phule Library at Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh/Twitter

Ashoak Upadhyay

“The public is not prejudiced. People are united by a shared bond, they gather for a collective cause. These days a mob is being termed the public. A mob never assembles on its own [but is] managed and herded into vehicles.”—Vinod Kumar Shukla. Hindi writer and poet from Chattisgarh.

[Hindu ya?] “Yes I am. I am also a Muslim, a Christian, a Buddhist and a Jew,” M.K. Gandhi

“Write me down. I am an Indian” Ajmal Khan AT

I

t had to happen. It had already happened. And it will happen yet again. Mobs will gather to support the citizenship legislations, they will confront protestors, willing a clash so that the police standing on guard nearby can rush in to target the protestors on the specious plea of maintaining law and order. And officials can then point to the ‘violence’ that the anti-CAA protestors indulge in creating a narrative of ‘anti-social elements’ or, as is current nomenclature, ‘anti-national interests’ breaking the peace, violently. So on Sunday 23 a BJP-led rally in New Delhi confronted demonstrations against the CAA. According to an Indian Express report the next day Kapil Mishra, a former MLA “who had been in the news during the recent Assembly polls campaign for provocative slogans, earlier in the day called people via Twitter to gather to protest against an anti-CAA demonstration,,,”

In Aligarh, demonstrators and police clashed, six were injured, two seriously; the policy deny they fired, even though they used tear gas to disperse crowds holding out that “miscreants” had pelted stones, damaged government and public property. As is its wont, the UP administration will seek compensation; it was also averred that women students from the AMU were instigating and that their “role would be investigated.”

These accounts tell multiple stories; the huge force of the state that is called into intimidating unarmed protestors; the language of repression that employs words such as “instigation” to condemn and then hang, as it were the “miscreants.” The possibility that some demonstrators might have pelted stones; the very distinct possibility that a police force armed to the teeth with weapons and an indoctrination laced with hatred for the students and especially girls, both of them demonized as scions of privilege in need of a sound thrashing; in effect, a surging masculinity that inebriates state apparatuses with the toxic fumes of unprecedented power.

Two months into what is undeniably the most historic civil disobedience movement in India since Independence there is plenty of evidence that the violence has been heaped on demonstrators; that by and large the sit-ins and marches have been non-violent, abiding and inspired by the Constitution, aiming at the expressions, historic in their own right, of love for all humans and religions in the way that would have earned the approbation of Guru Nanak and all the sages that contributed to India’s unique experiments with the truth of human diversity.

Is it any wonder that Sikh farmers from Malwa region in Punjab set up langarsat ShaheenBagh? What better way to express solidarity than by setting up a rasoi/langar? Ways to the hearts and mind of the protestors, history forgotten, mythic traditions restored. This was an updation of SIta-ki-Rasoi; in a replay of an ancient tradition rooted in aboriginal culture of feeding as manifestation of divinity, of partaking of Mother Earth’s bounty never mind that the langar was co-run by Sikh farmers from the distressed districts of the Punjab. Sharing space with Muslim women making rotis. In the langars at ShaheebBagh we ought to read not some secular expressions of the solidarity of the vulnerable fighting for a common cause but tropes of a spirituality of giving. Of one-ness, of non-dualism that has been a unique feature of this land named after a river, a river that gains fulsomeness through other rivers till it merges into the ocean of one-ness. The langar was the fulsome river on its way to the ocean of song; a reminder that all life is one; As The Quint reported:

A Muslim protester pressing the feet of an elderly Sikh protester, a Sikh tying turbans for young Muslim boys, Muslim and Sikh men and women cooking langar together – these are some of the images from ShaheenBagh that have become symbolic of the amazing solidarity that the Sikh community has shown…”

That solidarity’s spiritual tones come across in more ways than one. The farmers carried placards with slogans in Urdu that mirrored their desire to ensure that “brothers” are never divided again as they were in 1947. Expressions of common grief bound the Sikhs through the memory of the pogroms visited upon them in 1984. Guru Nank’s cautionary that before we are adherents of any faith we have to be human first was on poignant display in ShaheenBagh.

There are other ways to read these encounters, all of them pointing to the uniqueness of this civil disobedience movement. ShaeenBagh became, with the arrival of the Sikh farmers, an expanded site of publicness, of a grounded community of dialogue and conversation, of an open-ended shared-ness of suffering. The Sikh farmers suffer huge agrarian distress. According to figures cited in The Quint, 501 farmers took their own lives in 2019 and 516 the year before. And yet at ShaheenBagh there were no resolutions passed, no manifesto for action to address specific grievances. The arena was a platform for a spiritual bonding of the marginalised sharing the grief of real and potential disenfranchisement. An ocean of song.

And it is non-violent.

![]()

With solidarity also comes a new self-awareness. In what must be a unique facet of an extraordinary civil disobedience movement, the publicness of the Political finds expression in the birth of the free library and reading spaces.These libraries offer the space and materials for for reading, contemplation and discussions. Commentators have pointed to the common feature of libraries in various sites of protests across the world; from Turkey to the US where the Occupy Movement had a flourishing library to Honkong, Egypt.

In India, the idea of the public library has multiple registers of resonance. To begin with, the library at the Jamia Milia University, “Reading for Revolution” sends a strong message of resistance to the State that had sent its police force on a rampage into the official reading rooms of the University; that message has at its core the idea that civil disobedience creates its own spaces for reading, spaces liberated, even temporarily, from the domination of the State machinery. The ‘Reading for Revolution’ library like all the other sit-in site libraries in India is not the site of solitary solipsistic contemplation for self-improvement but a platform for that and the articulation of questioning.

The sit-in library such as the Fatima Sheikh/Savitribai Phule library at Shaheen Bagh or the Park Circus library in Kolkata among a host of others are not public libraries in the traditional sense of the word; privileged sites funded by philanthropists and civic authorities like the New York Public Library or the Asiatic Library in Mumbai. These sit-in libraries are public in the sense of being sired in the public sphere of civil disobedience against unjust laws. Their episteme is radically different to start with: it is based on the profundities embedded in the act of questioning. So the sit-in library begins with and underscores the performance of that basic act of the Political: inquiry and questioning.

Inquiry and Questioning precede Reading; to question is to read; the public library inverts the relationship in an invigorating way leading to a mutually reinforcing performance: questioning to read and reading to question. To read, Joyce Carol Oates once said, is to slip into another’s soul and skin. To empathise with the characters, the subject at hand; with the writer.But in these libraries of publicness, of “spoken-ness” the participant has at the very outset slipped into other skins; empathy is already at work engendered by the solidarity of questioning that brought them here to create this Reading Room. Susan Sontag once described her library “as an archive of longings.” The sit-in protest libraries are archives of belonging.

And more. The libraries, regardless of the kind of books they have, and news reports suggest, the Constitution is a favourite especially the Preamble, become sites of an insurgent spirit. The common meaning of Insurgent is one who rises up against the government. But its etymological roots lie in the verb insurgere which can also mean to rise up, to stand tall, to gather force and of course to rise up against something, someone.

The libraries provide the site for all these meanings: insurgent because disenfranchised women, homemakers without formal education, children without learning tools and books and students driven out of their cloistered formal sites of reading by a violence-drunk state, can rise up, stand tall and claim their citizenship of a humanity united in their diversity. Like the langar, the library is an expression of solidarity in learning; in giving. Both being forms of disinterested love

Insurgent because they represent the most vivid public expression of dissent against the marketization of education that makes access to books and reading increasingly exclusive. This marketization will gather will gather speed if the Chief Economic Advisor’s recommendations for turning education into a site of‘wealth creation’ grabs this government’s listless imagination.

And insurgent because they have the potential to reassert the power of reading increasingly condemned as an unnecessary and wasteful act, a burden on time better spent in quick and instant gratification, in twittering away one’s life. In an age of Instagram communication, with the endless immersion in the Spectacle who would want to read books except to pass exams? The sit-in protest reading rooms provide its member-promoters the opportunity to recover the faculty of reading, of interpretation, of ‘writing’ their own text on the author’s text, to understand why reading was and is considered a subversive act by governments across space and time. To reaffirm the praxis of Reading.

In effect, the reading rooms are celebrations of both self-renewal and the obliteration of the dualities that divide Us and Them, ‘we’ from ‘they.’

Both the libraries and langars are touchstones by which to gauge the historic significance of the anti-CAA protests; by that we would not mean a telos of significations with which we can measure the results or goals achieved by such protests. BY historic one would mean unique to its time, a gathering and coalescing of sentiments and behavior rooted both in tradition and a modernism that Rabindrantah Tagore would have recognized.

Tradition because the protestors subliminally draw upon an Indic cultural trait of pluralism,of an accommodative openness and resistance at the same time. You can be a theistic or atheistic , that hardly matters to Hinduism; as Margaret Chatterjee reminds us the matter of God’s existence is no great deal. Chatterjee cites the late Professor J.L. Mehta on the Indian tradition thus:

“ ‘…it has at no time defined itself in relation to the other, nor acknowledged the other in its unassimilable otherness nor in consequence occupied itself with the problem of relationship as it arises in any concrete encounter with the other.’ “ (Chatterjee, p 40. Emphasis in original quote)

This idea of “letting-be” also hints at the absence of inter-faith or inter-cult disputations; the paths to God are recognized as many, they are all equal and you do your thing and I do mine. Sixteenth century Eknath’s celebrated poem of a dialogue between Hindu and Turki is acerbic playful but it begins with this reminder:

“The goal is one, the ways of worship are different” (Zelliot,p69)

The tradition of accommodation carries into the twentieth century with Gandhi writing in the Harijan in 1934:

“…in practice, no two persons I have known have had the same and identical conception of God. Therefore, there will, perhaps, always be different religions answering to different temperaments and climatic conditions. But I can clearly see the time coming when people belonging to different faiths will have the same regard for other faiths that they have for their own. I think that we have to find unity in diversity… We are all children of one and the same God and, therefore, absolutely equal.”

Those protestors out in the sit-ins across the country are the children of this ancient tradition of letting-be, even if many of them might be non-believers; the fact that they have built grounded communities of polyphonic faiths znd beliefs underlines the existence or should we say resurfacing of that ancient tradition of accommodation in a defiance of historical time.

And yet the protests signify a modernism in that they are grounded on a modernist conception of rights embedded in the Constitution; a modernism as distinct from a modernization that is linked to the Nation-State and capitalism. While the specificities of that modernism are yet unclear and perhaps inchoate among the protestors given the absence of any articulation about the damages that modernity has caused Indian society and the world at large, the concept of modernism, that Tagore felt aligned to as representative of the “Spirit of The West” would seem to inflect the movement in more articulate ways.

This modernism represents the top layer of the palimpsest of consciousness evident in the protests. A modernism is grounded in civic mindedness, social and legal institutions and what Tagore felt to be “love of justice.” (Bharucha,94-95).

At its most protean level then the protest against the citizenship legislations mark a decisive moment in what could be called the subaltern consciousness of a people facing multiple levels of disenfranchisement, a consciousness that heralds in non-programmatic ways an attack also on patriarchy, on caste inequalities. Precisely because these articulations are manifest in praxis primarily they have a potency that should outlive their contingent impacts. It is not so important to gauge their effectivity in terms of outcomes; that positivist approach misses out on the moral and ethical basis of the protests, their unstated yet loud articulations against the foundational props of unethical and juridical inequalities and injustices manifest in assaults on womanhood and Dalits and Muslims, and who knows, on other religious minorities that are now being wooed to align with the majoritarian side.

And let it be said that precisely because of its palimpsest consciousness, expressive of modernism’s virtues of justice, civic mindedness and respect for constitutional law and a traditional celebratory open ness and one-ness, the protests are markers of an India that provides a stark contrast to Pakistan. The protestors posit an idea of India that the rulers of Pakistan, the real powers behind the façade of electoral democracy, the clergy and the army, would find fearful. A power based on a state-mandated monotheistic faith, on unquestioned unaccountable military might and bigotry, in effect a theocratic-military complex ruled nation-state would not welcome the protests as they are constituted, as sympathetic to their own brand of religion-based nationalism. Such protests could hardly legitimize their bigotry in the eyes of the populace. In fact, te reigning powers should fear such protests as subversive inspirational tropes for their subjugated peoples.

On the other hand, a majoritarian India would help the rulers immensely for it would legitimize a state of nationalist-religious hatreds for the ‘enemy.’

So let us be clear: the anti-CAA protestors are not “traitors” or egged on in any way by our “enemies.” They serve the “national interest.”In fact we could say that they define the national interest by harkening to its admixture of traditional openness and civic minded modernism enshrined in the Constitution.

We ought to be proud of that celebrataory blend of the traditional and the modern; of the men and women, students, children and grassroots leaders, beaten,jailed, rendered homeless, bankrupted with punitive vengeful fines who give meaning to an idea of India the constitutive parts of which are essentially as important in themselves as their sum.

An idea that defines in its performativity, love for your watan, our differences, in a word, patriotism.

‘Saare Jahaan Se Achha, Hindostan Humara’

(Protestors at Jantar Mantar, New Delhi)

![]()

Reading Room at Kolkata’s Park Circus/Twitter

*****

Notes Chatterjee, Margaret: Inter-Religious Communication: A Gandhian perspective.Promilla & CO. Publishers. New Delhi 2009. Zelliot, Eleanor in Richard Eaton ed: India’s Islamic Traditions 711-1750. OUP New Delhi 2003. Bharucha, Rustom: Another Asia: Rabindranath Tagore & Okakura Tenshin. OUP New Delhi. 2006.

Also read in The Beacon:

Leave a Reply