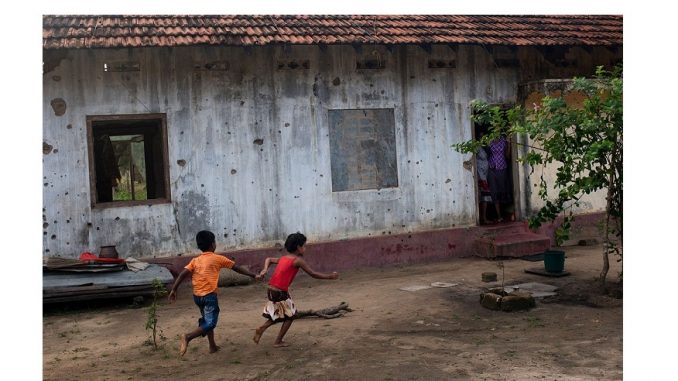

Children outside their bullet-riddled home in Mullivaikal scene of the final battle of Sri Lanka’s civil war.Miguel Candela/Al Jazeera

Preface

“Every translation implies a reading, a choice, of both subject and interpretation, a refusal or suppression of other texts, a redefinition under the terms imposed by the translator, who, for the occasion, usurps the role of the author.” Alberto Manguel

“It is the politics of everyday people who go without any mention in books of history. I wanted to be a historian of their spilt blood.” Ahilan

There’s no gainsaying how translators come by their work. The quotidian route to a project of translation is for a publisher to contact a translator and ask her to do the needful to a classic work of fiction or poetry with a foreknowledge, a business sense of the translated work’s receptivity; changing tastes in a globalising world of reading, an expanding market for specific genres of writing which publishers assume they have a handle on. Language changes; every generation has its ways of reading and publishers often sense that a classic like Flaubert’s Madame Bovary would do well, rise from the ashes as it were to adorn post-modern bookshelves were it subjected to a fresh translation. So Lydia Davis’ arguably tasteful translation; so also re-translations of the Russian classics. Sometimes authors blessed with bilingual felicity work their own translations with, once again arguably readable results. Qurratulain Hyder trans created Aag ki Darya as River of Fire, S.R. Faruqi did a masterful translation of his own Urdu novel into Mirror Of Beauty. It seems so prosaic, this origin of the translator’s efforts to re-create a world from a language alien for many and make it accessible to a wider readership.

Something’s lost, something’s gained in the endeavour. Alberto Manguel may feel Borges’ Spanish loses in the English translation but who can deny The idiot comes to life with Constance Garnett’s rendition of Dostoevsky’s classic? Yet who can also not want to savour newer translations of his works. Mohammed Umar Memon’s translations of Manto resurrects him with such a refreshingly keen yet sensitive rendition into English that a reader may be forgiven for believing she is reading the subcontinent’s greatest short story writer for the first time. Sometimes you never cross the same river twice.

There are moments in a translator’s life when the craft, if you wish, can emerge as a mysterious flame in a mind perhaps ready for its warm glow. Such seems to have been the case with Geetha Sukumaran who was inspired to translate the Sri Lankan Tamil poet P. Ahilan:

“In a crammed subway, while returning from work I opened a thin volume of poems with an unusual cover and front page. The words in that skimpy volume unlocked a multitude of images and emotions. Overwhelmed, upon exiting the train I sat on the platform, reading them over and over. At once, the poems were enmeshed in my heart, and soon I realized that the only way to get them out of me was by translating them”

This moment when that cognitive flame is lit occurs in Toronto, Canada; the poems Sukumaran reads are written in Tamil; her mother tongue. A bridge is built to far away Sri Lanka; the reader on that subway bench travels across space and time, in the blink of an eye, to the scarred terrain of Ahilan’s poems, war-torn north-east Sri Lanka in the mid 80s, to the carnage and massacre of a minority Tamil community by Sinhalese government forces in a civil war that bred its own blood-dripping aesthetics and poetic articulations of pain and anguish at loves lost and the memories they breed. A cathartic necessity permeates the reading: to render into an alien language the experiential holocausts Ahilan represents with what Sukumaran will describe as clinical detachment and a poetic aesthetic. The world of Ahilan becomes a burden and translation, we are told is the only way to rid that young reader of the spell cast over her that evening in a Toronto subway station. Her ‘escape’ from the well of Ahilan’s poetry into which she has fallen is to recreate it—in another language.

We do not know how Sukumaran journeyed to that destination where she drops off her offerings for an English-speaking world. The moment of epiphany if you will, must have passed. The work of the translator involves, as so many have told us, a paradox: travelling into the world of the original text while staying rooted in the language into which she will render it into a ‘new’ text for a reader whose world is perhaps even more alien to the original text and who will ‘read’ the translation differently than either, thus in effect forming yet another text. The trauma of pain aestheticized into a poetics by Ahilan may perhaps be rendered as a secondary pain felt by the translator; in the third round of reading trauma may turn into blood and gore but who can deny its visceral poignancy in these violent times?

The messages of loss through State violence so remarkably palpable even in Sukumaran’s translations could form tropes of present-day hegemonising violence against the helpless around the world. Those whose bodies and tongues are broken. Muhammad Amin’s elegy for Alan Kurdi, the refugee-boy washed ashore lifeless resonates not only because of the murder of innocence but because its voice echoes hope at the end: “Alan Kurdi’s voice reaches me/ ’Amin, Amin, listen to me/I was put into the sea/ Like Moses. Don’t you see?’ ”

In Geetha Sukumaran’s translations of Ahilan’s poems the reader gets echoes of that profound voice laced with a clinical tone even when alluding to a bloodbath that drenched parts of the island in the final phase of the armed conflict. The fact that Sukumaran places her English rendition alongside Ahilan’s Tamil original leaves the reader literally with two texts, two sensibilities; perhaps the English version appears sanitized in its evocations bereft of Tamil’s ancient lineages, its cultural forbears and signs from which Ahilan would have savoured ecstasies of influence while pondering the banality of evil: ecstasies that Sukumaran, as reader-translator would have also experienced at the crossroads of her journey to another text with its own sensibilities and representations of experiential horrors that organised power wrecks upon the vulnerable.

Sukumaran draws upon her readings of the western canon for analogies of the human; upon Marcel Proust to express the graphic of bodies being the repositories of “torpid memories” as she reminds us in her illuminating Introduction to Ahilan’s poems, “There were no Witnesses”

Lines such as these:

“Ragged garment,beneath,

another rag of pus,

with a clotted wail.

One breast gone,

on the other lay a tiny body;

inseparable.”

These “torpid memories” will reverberate endlessly in refugee detention camps, boats on the oceans of despair ferrying victims of persecution, drug-related violence, climate change and in the killing fields of neo-imperialist wars.

Sukumaran translates a poet of war and its savage effects on the helpless. And her bilingual presentations provide fertile ground for multiple readings. As she points out in her introduction, “A Tamil reader or anyone familiar with the Sri Lankan political scene might recognize the scene as reminiscent of the carnage in Mullivaikkal, a region in the northeast of Sri Lanka, where state-led forces defeated the insurgents (LTTE) in 2009. The poet’s language is striking in the way it enfolds the vulnerability of human existence, the act of witnessing and experiencing pain.”

In a protean sense, Ahilan’s poems join the ranks of what Nadine Gordimer called the essential gesture. The world and “that lifetime lodger, conscionable self-awareness” can call a poet to account; the “creative act is not pure. History evidences it. Ideology demands it. Society exacts it.” In the Garden of Eden, Sri Lanka, the Serendib isle, Ahilan must lose Eden. And he must have known that his creative act was embedded in what Gordimer terms “congenital responsibility” to which he is ‘held’ before he even begins, “by the claims of different concepts of morality — artistic, linguistic, ideological, national, political, religious — asserted upon him.”

And that essential gesture is captured in Sukumaran’s concluding passage to her Introduction:

“Ahilan’s poetic oeuvre is thus a register of history, a witness to trauma, and a counter-memory…The strength of the poems lies in their combination of cultural elements, spirituality, physical rawness, and postmodern aesthetics…his poetics…explore the precariousness of human relationships in the contemporary world of conflicts.”—Vinay Hameed

*****

![]()

Geetha Sukumaran and Ahilan Packiyanthan

Geetha Sukumaran

I

Profiles of “Torpid Memories”

P. Ahilan was born in 1970 in Jaffna, Northern Sri Lanka, a region engulfed in ethnic violence for years. He teaches Art History at the University of Jaffna in Sri Lanka. He began writing in the 1990s and has published two collections titled Pathunkukuzhi Natkal (Days of the Bunker, 2001) and Sarama kavikal(Elegies, 2011). P. Ahilan is one of the most prominent contemporary poets in Tamil. His diction, imagery, and minimalist style sets him apart from other poets of his time.

His poetic style expresses decades of violence in Northern and Eastern Sri Lanka with great nuance and subtlety, producing a unique voice. As an art historian and a poet, he blends the two-thousand-year old Tamil literary tradition, mythology, history, culture, and philosophy to create a rich body of work. The Christian notion of passion is a recurring trope through which P. Ahilan articulates the experience of pain and loss.Elegies is a collection about the final war of 2009.

The poems in this volume are voices of witnesses and victims that subvert the grand retelling of 2009. By creating fragmented narration of the scenes of war, the poems produce a jagged landscape of collective memory in a clinical language.

They intersect individual grief of ruptured relationships and the collective trauma of war while engaging with personal and political realms. The personal poems on human relations are structured in a language of excessive violence similar to the political poems on the catastrophic events of 2009. Devoid of embellishment, these poems amplify the immediate urgency and the ultimate inadequacy of words in the face of the extensive horror of violence affecting individuals and communities. While a Tamil-speaking reader can register the specific circumstances of the poems, non-Tamil readers respond to the language of violence and trauma of both the public and the personal.

A Mother’s Words

In the endless nights

the split open earth

witnesses blood.

Who are the children

waiting for in camps

muddied by sobs?

No son,

No father,

nothing ends.

The desolate

walk their life

with feetless legs.

Once,

there were houses here,

there were villages here.

An eon

deluged by the sea

in the silence

of history.

Him and Her

As the night snakes

the air drinks in sleep.

We savour cruelties

ripping off blood ties

in the anger

spit by an insect

sundered from

the body.

We speak

love’s phrases

eyes welled up

with venom,

in the worm infested bed,

lies swarming the genitals.

A nomad laughs

splintering time.

A stranger exits

opening endless doors

II

In Conversation

“Poetry is [a] pilgrimage undertaken by words, endlessly towards their beginnings.” Ahilan

“, i wish to make a skinned language of blood and flesh my form of expression.”Ahilan

The first collection of poems by Ahilan, who is part of the generation of poets that began writing in the 1990s, titled Padhungu-k-KuzhiNaatkal [Bunker Days] came out in 2001. His second collection, titled Saramakavikal was published in 2011. Born in Yazhpanam [Jaffna], in the northern part of Sri Lanka, he holds a Bachelor’s degree in Art History from University of Jaffna, and a Master’s degree in Art Criticism from M.S. [Maharaja Sayajirao] University, Baroda, India. Presently a Professor of Art History at the Fine Arts department (Faculty of Arts}, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, he has co-edited the second and third parts of Ilangai Chamugathaiyum Panbaattayum Vasithal: Therivu Seiyapatta Katturaigal [Reading Sri Lankan Society and Culture: Selected Essays] (2007, 2008), and Venkat Swaminathan: Vaadhangalum Vivaadhangalum [Venkat Swaminathan: Arguments and Debates] (2010). His most recent book is Kaalathin Vilimbu: Yazhpanathin Maraburimayum Avatrai Paadhukaathalum (2015). Excerpts from the conversation I had over phone and email for the 50th issue of Kaalam, with the poet.

Geetha: In his review of Padhungu-k-KuzhiNatkal, Mu. Po.identified your creations as a unique “poetics” which “does not let unneeded particles and infinitives rain down, or allows those particles that fall into place to stand as complete nouns”. How did you craft such a language, or did the backdrop of your life shape it? Did the influence of other writers have a place in your language? Your poems have forged a new, clinical, and minimalistic mode of language in Tamizh.

Ahilan: All creations have a kind of intertextual nature to them. No creation comes into being outside a long and consistent creative ethos. Each has its own genetics and ecosystem. With Padungukuzhi Natkal, i feel that Chingiz Aitmatov, Anna Akhmatova, and Sukumaran have influenced it in their own ways. At times, apart from literary texts, paintings and performances have also exerted their influence. I do not know what to say about Samarakavikal.

About the language of Saramakavikal, all i can say is, that the form was discovered by the content. It is possible that my ideas concerning poetic language are the mechanics behind what you have identified as the minimalist character of my writings. The use of language, which Mu.Po.identified, is also, i think, a product of this backdrop. Because i think that no word that is an excess to a poem must be placed in it, and those that do find a place must be forged till they are at their sharpest.

The ‘clinical language’ that you had observed with regard to Saramakavigal, i think, is a result of a use of language that is on a kind of observation and diagnosis. This acquired shape from the central themes of poems like “Vaithiyasalai Kurippugal” [Hospital Notes]. Notably, the third-person speeches in these poems–the records of losses and remains presented in the form of statements–might have led to the ‘clinical language’.

At the same time, the rawness of language attracts and pulls me in. That is, i wish to make a skinned language of blood and flesh my form of expression. I think that this raw quality is present in Saramakavigal. My expectation is, at the same time, that words becomes the bodies for what they speak of; that, when they speak of blood and pus, they acquire the liquid qualities of blood and pus themselves.

G. In your creations, you use the grotesque violence of the external world as sediments of mindscapes. For example, we may note these lines from “Midhunam01”: “Rotting tongue delights in piercing the heart with words mixed in saliva.” In many lines like these, the grotesque, and morbidity associated with it, seem to find their place. Nature, Beauty, and their tenderness, are entirely absent in the themes of these poems. How would you explain this?

A. I am not sure how to explain it. But, what you say is right. My humans are, for the most part, unpleasant. The experiences instilled in them by their times, in particular and total ways, have turned them into singers of morbidity. I did, of course, desire for them to sing of the sea and the corners of the moon. Their times, however, turned them into singers of death and fat. It turned them into people who peered intently at death. They had seen uncertainty in flesh and blood. They began wandering like foreigners behind questions concerning the meaning of their existence. Slipping from contemplations of such existential questions, born from the pain and despair of being witnesses to atrocities, they become entrapped in their sexual desires.

G. Another question arises along the same wavelength. I see two states–of ‘Ulappadu’ and ‘Tiruppadu’–as underpinnings of your poems. The English word ‘Passion’ exists as a common term denoting both the outrush of emotion, and the tiruppadu [suffering] of Christ. I feel that this conception functions as a bridge between the internal and external in your writings.

A. In its Latin root (Pati/Passio), the word ‘Passion’ also means “to suffer” and “to endure”. I think that the ‘Ulappadu’ and ‘Tiruppadu’ that you identify in my poems function at their sorrow-laden origins. The word ‘Passion’, in subsequent centuries of the English language’s development, soon acquired new meanings like “intense emotion” and “desire”.

‘Pathos’ is another word that branched out from this same root. In the 16th century, the word also came to denote love born out of an overflow of emotions. Although meaning can be made of my poems through all these strands of meanings, i think that my lines travel through the 17th century’s imaging of the ‘Passion Flower’. It is said that the flower of passion, in another sense, is connected with the conception of the ‘Crown of Thorns’ in Christian theology–that which stitches the wounds to the body.

Thus, my Radhai stands as one alone, waiting, and suffering from her memories. In many instances, endurance as an attribute of self-torture comes and goes as an aspect in many poems. In a single night, my Jesus faces many thousand denouncements, suffers betrayal, and, as his eyes turn towards the Father, his blood drips down as one with his tears. They [Radhai and Yesu/Jesus] are wounded. Their tribulations construct them. Thus, we can say that the aforementioned intense element of passion is also that of trauma. Kaayam [wound] is another word for Dhegam [body] in Tamizh, is it not? Isn’t it, both from within and without, a wound-urn? Is it this self-same wound-urn that i bear along from day to day?

G. This, you say, is your poem’s wound… On destroyed minds, on tormented bodies, on human sorrow, the human plight, bearing the weight of age-old war-wrought catastrophes, your poems take their stand. On these they make their inquiry. They do not engage [however] in commentaries on the oppressive politics which forms the root of this. Can we assume that your notion, that this should be so, is an expression of your subconscious as it relates to the existentialism of the individual as an oppressed subject belonging to a minority community?

A. Maybe. A certain self-censorship might have played a part in them. At the same time, i have no interest in expressions that take propagandist stances. I do not believe that, to talk about revolution, one absolutely needs rifles and cudgels. But i do feel that there is a very pointed minority politics in my writings. It is the politics of everyday people who go without any mention in books of history. I wanted to be a historian of their spilt blood.

*********

Notes Preface --First quote from: A Reader on Reading” Alberto Manguel.P 202.Yale University Press. 2010 --Sukumaran’s quotes in the Preface from her Introduction to Ahilan’s poems, “Then There Were no Witnesses” A bilingual Tamil-English Edition. Translated by Geetha Sukumaran.Mawenzi Press 22018 --Nadine Gordimer quotes from: The Essential gesture: Writers and Resonsibility. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Delivered at The University of Michigan October 12 1984. Profiles… Courtesy: Postcolonial Text, Vol 10, No 3 & 4 (2015). Original title: Song of the Dark Times: Poems of P. Ahilan In Conversation… Kalam is a Tamil magazine for literature and arts (quarterly) published in Canada. It is printed in India and connects Tamil literary zones from India, Sri Lanka and the diaspora. Editor Selvam Arulanantham, who is also a writer (his memoir is recently published by Kalachuvadu, ( a renowned magazine dealing with content in politics, literature, arts and social issues)Geetha Sukumaran is a doctoral student in Humanities at York University, Toronto. Her interests include contemporary Tamil poetry, women's writing, trauma literature and translation. Her current research focuses on Tamil women's writings from Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu that connect culinary practices with war trauma, memory, familial and caste oppression. She has published two books in Tamil: Tharkolaikkuparakkumpanithuli (Tamil translation of Sylvia Plath's poems, 2013), and her own poems, Otraipakadaiyilenchumnampikkai (The Hope that Remains in a Single Die, 2014). Her English translation of Ahilan's poetry titled, Then There Were No Witnesses, was published by Mawenzi House, Toronto (2018). She is the recipient of the SPARROW R Thyagarajan award for her poetry.

Also read in The Beacon:

Leave a Reply