Ashoak Upadhyay

“The purely economic man is indeed close to being a social moron.” Amartya Sen

“ ‘Would you tell me please, which way I ought to go from here?’ ‘That depends a good deal on where you want to go.’ said the Cat” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Ch 6.

P

ick up one of the financial newspapers or cast a weary eye on a Google-ed report on the economy and you get the inescapable feeling that reality is a flexible category and alternates between various shades of the unreal often moving into the hyper-real. Economic growth as measured by the GDP is hurtling down towards a bottom that is not yet in sight though some may aver that it has already hit the bottom; ‘bottomed out’ and the only way is up. The fall in the GDP seems fantastical because it does not augur pain or death or a state on un-well being of humans but a quantitative outcome whose fluctuations or peregrinations are the center of all policy initiative.

The prosaic world of economics , that dismal science has been long leavened with poetic metaphors and allusions that were perhaps meant to enliven the dreariness of the discourse itself; at the end you , the reader would glean the idea that you were screwed by forces that you had only a dim understanding of but in a rather graphic way and through abstract (read as quantitative) representations. But the metaphor of a number falling down towards a bottom carried the hope that at some time the hole we are in would well, bottom out’ and defying all theories of the real the thing that had fallen would begin its journey back to life at the top.

And if the GDP rose once again so would we because the GDP does not measure our state of being , it is our being.

All the discourse on the Gross Domestic Product is about economic growth is about our fortunes as a society. The GDP is a number, a metric that is supposed to be a measure of our materiality the constitutive elements of which are arbitrarily selected by statisticians and policy wonks. These could include drug sales (as in Columbia in latin America), prostitution and heroin sales (as in UK in 2012) or the inclusion of the Mafia within the text net as in Italy that turned its GDP higher than Britain’s. But read the news, official reports on economic growth and you get the feeling that it is no longer a measure of growth but an end in itself. The model, a theoretical construct has become the reality stripped of all ethical norms it would seem,

The GDP as the reality of our existence reflects a totalitarian perspective that views reality as a mobile category to be molded, reshaped or created by selective deletions and accretions. The process results in the emergence of what at first glance appears fantastical in that a number comes to life as the metonym of human endeavors and anxieties. The GDP number with its whimsical qualities and yo-yo movements appears in our consciousness like the nose in Gogol’s The Nose, or Dostoevsky’s The Double. Parts acquire the reality of wholeness, doppelgangers shadows become substances,

But you realise that the GDP is not Kovalev’s missing nose or Mr. Golyadkin’s double, alter egos exposing human frailties. The GDP substitutes the real; it is not part of the whole, nor does it cast light on the whole; it is a meme for a complex reality that is hidden away or erased from its being and, in its narrative from the public eye. It is a number, a metric surely; it measures certain quantifiable categories of goods and services. But the assumptions that it is adorned with accord it a presumptive and false omniscience that purports to speak for the welfare of human beings even as it denies their existence as human beings.

No respectable economist, policy wonk can ignore to pay obeisance to its majestically ubiquitous power as the definition of a society’s prosperity. Least of all the economic mandarins in North Block and all those who figure they decide on the country’s destiny because they have a handle on the calculation of its GDP.The nation-state’s infatuation with GDP has stripped discourse on national “development”of its distributive concerns through that process of deletions reminiscent of totalitarian reality-molding selectivity since 1991 when neo-liberal “reforms” transformed a metric into its own end. The number is a measure of its own existence. Being an end in itself, it has been bestowed its own language, its own scripture that in turn speaks to itself. The GDP is the nation. The identity is complete and inviolable. The GDP speaks for itself and by that token defines the fate and the conduct of the Nation-State.

Deconstructing its journeys, its states of being is the full time job of bureaucrats, academics and the talking heads who spend their entire professional lives in the service of that number and by that token in the service of the Nation-State. To read their views is like a travel into hyper-reality; their language emits a scent of change that could be liberating or apocalyptic. Of late it is the latter, the whiff of doom and gloom spreads across your consciousness as you read of the plummeting GDP and you know that you, dear reader, are walking through a looking glass wood, where numbers are yet to hit ‘bottom’ though some will tell you they have bottomed out. .

The journey begins thus: “Six-year low–and slow”

With this dramatic and cryptic headline that invites the reader to read on, the first para (Indian Express Nov 30, 2019) states:

“Dragged down by contraction in manufacturing, weak investment, and lower consumption demand, India’s GDP growth rate at 4.5 per cent for Q2 2019-20 hit a 26-quarter low in July-September according to data released by the National Statistical Office…”

On your way through the looking glass you also read: “This is the lowest quarterly growth rate in the five-and-half years of the Narendra Modi-led NDA government…”

You have arrived in the kingdom of numbers where for the moment Duke GDP, has fallen off the high stool. You walk in a daze among those numbers still falling and you hear the talking heads echo around you:

–GDP growth at 5% in Q1 FY20 has been significantly below our expectations. India is now behind not only China, but also the Philippines and Indonesia in terms of real growth rate. While the slowdown is broad-based, the deterioration is most marked for private consumption and manufacturing.Yet, at least 7.5% growth would be needed in the last two quarters to reach even 6.5% growth for the whole year, which looks like an uphill task. Sujan Hajra, Chief Economist and Executive Director, Anand Rathi Shares & Stock Brokers

–National accounts data is consistent with the picture suggested by leading indicators for Q1. GDP growth has decelerated to 5% – the lowest since Q4 FY13. There is an acute slowdown in the manufacturing and agri sectors on the back of a slowdown in aggregate demand – both consumption and investment demand. Except for mining activity and power generation, all other productive sectors have slowed. In our opinion ..“Rupa Rege Nitsure, Group Chief Economist, L&T Financial Holdings

–Given the indications we have seen in the past few months, growth was expected to be slow. However, 5% is far below Street estimates of 5.6%-5.7% and does come as a surprise. This was primarily driven by lower growth in private consumption. Manufacturing growth staying almost flat is also worrying and immediate steps are needed to revitalise this sector. An overall recovery may take another couple of quarters as the NBFC ..Gourav Kumar, Principal Research Analyst, Funds India.com

–GDP growth has come in line with our forecast of 5%-5.2%. The slowdown is being felt across sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing and services. A strong base effect from last year only added to the pain. Going ahead, we are looking at activity improving from these lows. This could be the bottom for the current slowdown..”.Sakshi Gupta, Senior Economist, HDFC Bank (ET)

A voice of authority and certitude chimes in;

—We are saying again that the fundamentals of the Indian economy continue to be strong. GDP is expected to pick in Q3, Chief Economic Advisor KV Subramanian… (BT)

You get a creepy feeling that even though the voices sound different, words too, they are saying the same thing. The Emperor-Number has fallen! It will pick itself Up! Like echoes of echoes they ripple away into infinity or into emptiness.

The fog of incomprehension envelops you. Sameness stalks you; words signify nothing.You shake your head to rid it of the lingering echoes of the voices from the void. You want to think this through. But in this wonderland, you are like Alice:

“I’ve got a right to think’” said Alice sharply for she was beginning to feel a little worried.

“Just about as much right,” said the Duchesss, “as pigs have to fly.” (Alice…Ch 9)

You are awake. The echoes have faded into nothingness replaced by the tinnitus hiss of an uneasy silence. Images scatter across your consciousness some surfacing like fetid bubbles, memories of grotesqueries that sometimes you laughed at; sometimes wept over but most often than not, simply forgot in the pursuit of self-satiation and benumbed obedience. But now they come back, like cryptomnesia shards strangely invigorating: memories of lynching, farmers’ suicides, of unemployed youth of raped women and girl-infants and of boat people drowning off the shores of Paradise, of Alan Kurdi Syrian child of Kurdish descent washed ashore one of them never to stand up again, of refugees denied a place to procreate and watch their progeny do better than them…the air we breathe is fetid, the trees and rivers devastated consigned to oblivion. These nightmares haunt you; as do words that put meaning to them, words such as inequality, scarcity, injustice exploitation, anomie, fear environmental degradation; the list grows portentous with implications, imbricated into each item portraying an apocalypse of unimagined proportions you do not see reflected or even glimpsed in the solipsistic kingdom of the GDP number. A question in your nerves is lit: What is The Emperor of Numbers measuring if it doesn’t expose such maladies and evils of our inhumanity? Where are the People? In its self-centered pre-occupations, in measuring itself is it …mis-measuring us, the people? Misguiding us!?

And you reach out to the stack of books gathering dust on an even dustier shelf and yes! You have found Joseph Stiglitz. A slim volume co-authored with Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi has the same word you have just thought of even though the fullness of its naming opens a crack for the light to get in: “Mis-Measuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up.”

Then you read the Preface to this report compiled for the general public by a Commission appointed by the President of France at the time Nicholas Sarkozy who in 2008 set up a commission to spell out how metrics did not capture the complex reality of risk and scarcity all around us. As he put it in his Forward to the report that was released eighteen months later for public debate, we “march ahead blindly while convinced that we know where we are going.” Our belief in the infallibility of data creates “aa gulf of comprehension between the expert certain in his knowledge and the citizen whose experience of life is completely out of synch with the story told by the data.”

The authors of “Mismeasuring…” laid it out straight up front. In their Preface they assign the problem to a confusion between ends and means. The Commission was inspired by concerns about the adequacy of current measures of economic performance “in particular those based on GDP figures…concerns about the relevance of such figures as measures of societal well-being, as well as measures of economic, environmental and social sustainability.”

Since the problem is in the deficiencies of the GDP metric unable to capture the broader frames of reference the Commission alludes to—societal and environmental well being—the authors suggest that other traditional metrices may be able to approximate the complexity of our problems far better. “Unemployment has an effect on well-being that goes well beyond the loss of income to which it gives rise.” On the other hand, flawed or even biased statistics can often lead us into the trap of illusion or wrong policies. And delusional perspectives. How are we to evaluate the reaction to poor GDP growth numbers for the last quarter by Union Minster Ravi Shankar Prasad who proposed a new measurement of national prosperity?

“I was also told that on October 2, which is observed as one of the national holidays, three Hindi movies garnered Rs 120 crore business…Unless the economy is sound…how can only three movies collect so much business in a single day?”

Metrics shape our beliefs and inferences. The Hon’ble Minister is living proof of the power of the metric to inspire theories best kept for airing while having a shower. As the Commission points out apropos the GDP,

“There is no single indicator that can capture something as complex as our society.” It’s not enough to care about how we are doing “in the aggregate”—which is what the GDP tells us—we need to know what is happening to the distribution of income. We need to know not just how we are producing in the present but what we will be able to produce in the future, which means that we have to invest in protecting our natural resources so that future generations can enjoy the same air and natural beauty that we do or, which is more to the point, our recent forbears did..

The Commission does not wish to jettison the GDP as a metric only topple it from its position as the sole arbiter of national progress. Or stagnation. GDP measures production of market-driven goods and services, that is goods and services expressed in money units, adds them and offers up the rate of growth of the value of the goods and services so measured. But it does not atop there; the GDP metric acquires a patina of influence far greater than it should and stands in for and is equated with, national prosperity or decline. In the afore mentioned observations of the “experts” the common thread is the decline in production on account of various factors that distress them such as weak demand, slow investment leading to a decline in production.

But what the GDP does not measure, among other “services” is the value of domestic work done by women, the value of informal labour. What it does not tell us is the social and environmental cost of production, the price we pay and more important, future generations will pay for the erasing of a river to create the ground for a swimming pool, a gated community, all of whose values are added to the GDP.

Which is why Stiglitz and his co-authors felt the dire need for “our measurement system to shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people’s well-being” (emphasis in original,10). Well being not just of the present generation but of those to come. Sustainability acquires strategic importance in the calculation of well-being.

The Commission grounds its recommendations on this critique of the paradox of the GDP metric; that it is narrowly focused on the value of production of goods and services, that it is basically exclusionary in content and yet conflates its existence as a metric of national well being.

The authors therefore recommend that incomes and consumption be adopted as measures of well being instead of production. Goods and services can be produced extensively even with falling levels of employment and incomes as technology replaces labour or wages fall or, at any rate do not rise fast enough to cope with rising prices. Material standards of living measured by real household incomes, consumption and access to health care and other social needs measure far more effectively our state of well being than the fact of increases in the production of goods. And if you want proof of this cast an eye on China’s phenomenal growth as an export powerhouse supplying cheap goods to the developed world; they could do that only by keeping labour costs abysmally low.

China’s phenomenal economic growth measured by the GDP provided proof if it were needed that the metric had spread across the world marking progress creating that competitive animal spirit among nations eager to catch up with the West. India followed China down the road to treating the GDP as a key to liberation from the shackles of “backwardness.” Once “liberalization” had kicked in the GDP growth rate established itself as the marker of materialistic advancement—down to the present where the arch enemy of the UPA gladly embraces its neo-liberal philosophy stripped of any sideline programmes of a welfarist nature.

The Commission had pointed out a decade ago that to measure well being a “dashboard of metrics” needed to be adopted to reflect the multi-dimensionality of well being. So they suggested the following:

- Material living standards (income, consumption and wealth)

- Health

- Education

- Personal activities including work

- Political voice and governance

- Social connections and relationships

- Environment (present and future conditions)

- Insecurity of an economic and physical nature.(Stiglitz, 15)

But which country was willing to listen even after the financial crisis hit in late 2008 and recession soon after.Certainly not the GDP converts, such as India and China both of which had become “GDP junkies” And nobody paid attention to the shit hitting the ceiling. Faster than the United States, where the GDP had originated as a measure of national income it was in China with its rapid progress up the GDP ladder that the consequences on the environment of runaway production was felt: “suffocating smog, toxic drinking water clogged highway sand skyrocketing cancer rates.” It was so bad that a former civil servant commented:, ‘GDP doesn’t mean anything if you don’t have your life.’ (quoted in Philipsen, 134)

In 2004, with much fanfare, the Chinese authorities decided to undertake a ‘green’ GDP computation, calculating the cost of growth on the environment. The initial computations of the green GDP for the year 2005, published the following year were so devastating that the government abandoned the project after various provincial governments protested about negative GDP growth rates that showed up after adjusting for the environmental cost of growth. Overall, according to the initial estimates “20 per cent of China’s GDP was based on depletion of resources and degradation of the environment.” (Philipsen, 134)

That was in 2007. But as Jinnan Wang, one of the environmental scientists who worked on the pioneering green GDP studies that were shelved within a year pointed out in an article in Nature magazine in 2016, the efforts to develop a green index for China’s environmental costs have not ceased. More to the point, the official stance has also changed with the 13th Five year plan launched in 2016 that recognized the problem the country faced shouldering the dubious distinction as the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter. And one of the policies being pursued with some vigor is to encourage provincial governments to shift away from dirty coal to renewable energy sources.

Indian policy wonks slumbered through this all. To his credit, Jairam Ramesh as Environment minster initiated steps to introduce green GDP index that would reflect the cost of environmental degradation and depletion of natural resources during the course of growth. That was in 2009. Two years later an expert group led by Professor Partha Dasgupta of Cambridge University was tasked with creating a framework for green national accounts in India. The nation still awaits positive outcomes though the Dasgupta panel had submitted its report by 2013.

In the meantime the environmental damage continues unabated. India’s estimated geographical area is 324.78 million hecatres of which 96.4 million hectares or 30 per cent is already degraded according to the latest Living Planet Reportof 2018. The report also cites the Forest Survey of India data for 2017 that shows India has just 21.54 per cent forest cover left.

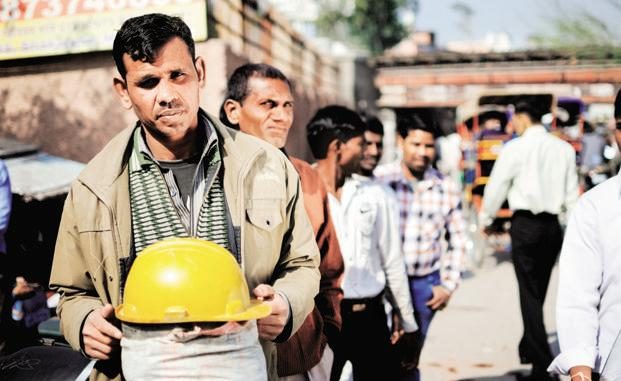

![]()

©Ronny Sen. Jharia.768×1024

But the chase for the GDP number still continues.India like most other nations does not seem to want to use any other metric to gauge prosperity; the “useful idiots” of the Nation-State and policy geeks sing in the shower when the GDP moves up an inch (or, as the case usually is by 0.3 per cent) and sob at the sink when it reverses track and inches down.

How did nations such as ours become GDP addicts?

II

“Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle!” (Alice…Ch 2)

The concept of the GDP was sired in the United States three years into the Great Depression and great confusion as to what had to be done in the face of such economic crises. Banks had fallen, firms too, manufacturing and jobs were down. With the onset of the financial crisis in 1929 and firms declaring bankruptcy, the biggest impact was felt on the working people and the rise of unemployment. As the Depression deepened reports about loss of jobs, then homelessness and food scarcities began to reach policymakers but no one knew how widespread the crises was becoming. And this sense of complacency and paralysis borne out of politics continued till 1933 when the pioneering efforts of one Senator La Follette would bear fruit.

For three years the senator had tried to convince a complacent and conservative Washington on the need for policies to aid the growing number of working unemployed by first collecting and computing reliable data to reflect the extent of economic collapse. One legislative initiative after another was defeated in the Senate. Then in June 1932 just two weeks before a ringing speech o the ravages of the Depression then in full force and its impact on working people, the Senate approved Resolution 220, he had authored. This legislation would request the Department of Commerce to report on national income for the past three years.

The Resolution seemed simple enough in hindsight; estimates of national income and portions of such income originating in manufacturing, agriculture, mining and what it termed “other gainful industries and occupations” and the distribution of such income into wages, rents, profits and other types of payments. But at the time, this was a novel idea as Phillipsen tells us, since extant “data were ruefully incomplete or too outdated to be of any use.”

The economist chosen to pioneer this gigantic task was Simon Kuznets. And as Dirk Phillipsen puts it: “With the approval of Resolution 220, the groundwork for launching GDP was laid.” (Philipsen, 82)

By January 1934, exactly a year after it was formed, Kuznets’ group submitted its report simply titled: “National Income 1929-32”.

The world had got its number, embedded in the three lettered acronym, GDP. For nearly eight decades nation-states, corporations and global policymakers not to mention talking heads have paid obeisance, swearing allegiance to its power as maker of destinies, the castle on the hill. If the journey involves the price of dirty air, depleted natural resources, joblessness so be it.

Even though…

Simon Kuznets wasn’t comfortable treating everything produced on the same footing; weapons kill, chemical pesticides/agents destroy the soil and the environment. They should not be added up along with primary health care centers dispensing generic drugs at discounted prices. He wanted to subtract products and services that harmed humans not add them. And that is why he was adamant that the GDP as it evolved in the early 1940s following his initial report was not a measure of wellbeing.

As David Pilling points out, he felt his accounts measure to do just that and that is why he wanted to subtract/exclude harmful products, government activities. Kuznets, Pilling points out in The Growth Delusion wanted a measure that would reflect welfare rather than just remain a “crude summation of all activity.” But Kuznets lost out and during the Second World War he acquiesced to pressure to include defense expenditure in national accounts.

That set a trend all across the world where GDP has become the metonym of prosperity. In Latin America, Columbia’s GDP waxed and waned as the drug cartels flourished or were chased away. In the late 1980s cocaine amounted to 6.3 per cent of its GDP. BY 2010 when the Medellin drug cartel was wiped out, that proportion declined sharply. (The Growth Delusion…)

III

“At last a bright thought struck her. ‘Why it’s a looking glass book, of course! And if I hold it up to a glass, the words will go the right way again.’ ” (Through the Looking Glass. Ch. 1)

Not too long ago at a campaign rally Prime Minster Narendra Modi laid down the template for India’s policymakers by which to combat the bad news being churned out by government statisticians. India, he thundered will be a 5-trillion dollar economy by 2024. In five years, India’s GDP will soar. We would have reached the castle, climbed the slippery slopes to a heaven awaiting at the top of the hill.

Coming amidst the gloom spread by economic numbers, by the trending down of the GDP the PM’s words held fast and have become the inspiration for thundering optimism among his minsters; the chariot of such a cosmically charged goal rolls over the potholes lining the dreary landscape of rising unemployment, falling incomes, dying or killed off income generating activities (meat exports for instance or dairy farming). Fewer women are in the workforce now than they were before and colleges are churning out more graduates than can be absorbed in jobs. And this is not just because investment demand is weak.

During the heydays of rising GDP growth during the two terms of the Manmohan Singh led government wages trended down; the rate of growth in employment was not in step with job growth. And so there is no use trying to convince ourselves that once GDP climbs so will employment. Higher rates of unemployment are the order of the day.

It might be pertinent to hark back to the words of Stiglitz and his colleagues that sustainability is eventually the issue predicated on rising incomes across the board. But with a retooling of labour in India and the rise of contractualisation of employment, real incomes will not be sustainable. The State of Working India report 2018 presents a picture of Indian youth that is not included in the GDP metric.

The report confirms the growing suspicion that jobless growth has been the abiding narrative of India’s growth in the recent past. Unlike in the two decades to 1990 when the average GDP growth rate of 3-4 per cent generated 2 per cent growth in employment; the GDP growth of the post 1990s and especially after 2000s when it reached 7 per cent employment slowed to just one per cent and even less. India is blessed with a demographic dividend but the dream is curdling since unemployment among the educated youth and higher educated has reached 16 per cent.

And what is the nature of employment being offered in any case? Various studies show a spurt in contractual employment across private and public sector firms in the organized sector. Maruti Suzuki had upped its contract-work force from 32 per cent in 2013-14 to 42 per cent three years later. In Coal India 62 per cent of the total coal was mined by contract workers. Termed variously as temp or flexi employment Indian producers like their counterparts elsewhere have got around the problems of “rigid” labour laws and are creating what can only be called a “precariat”, a working force stripped into what Aneel Simran has called “infantile dependence..” In “Retooling Labour to Infantile Dependance” that appeared in this journal Simran quotes the CEO of a leading ‘staffing’ firm:

“Economic volatility is a reality today and organisations need to be more flexible to accommodate market changes. The staffing market in India is already large considering the population in the labour pool and is poised for rapid growth. In the years to come, Indian staffing market will be the largest in the world…according to industry reports, the temporary workforce is likely to account for 10% of India’s formal sector employment by 2025. India has one of the largest flexi[ble] staffing workforce numbers in the world, next only to China and the US.”(Randstad)

It is possible that through some seismic changes in the global economy and a radically positive response from Indian industrialists to the overgenerous tax incentives Nirmala Sitharaman has offered them, with the RBI ever willing to cut interest rates, erase bank NPAs fund real estate barons unwilling to reduce property prices in their pursuit of superprofits, it is conceivable that GDP growth just might pick up. We could always hand over swathes of land to Chinese entrepreneurs, Saudi Arabian princes, Russian oligarchs who promise to Make in India, hand over Kashmir and the North East to Indian oligarchs-in-the-making and build superhighways crisscrossing the land for super-fast cars to zip around temples and sacred sites renamed for the various avatars of Lord Krishna, Ram and Rajput princes.,

But we shall have mangled the environment further; our rivers will have died even if the Ganga is cleaned at Prayagraj for the tourists to marvel at India’s heroic efforts to save the mother river. Temperatures will rise further killing people of heat, water shortages and foul air and our cities will sink further into dystopian futures. Our happy embrace of temp staffing and high tech would have chiseled away real wages even more, rendered greater numbers of graduates redundant in the labour force. With women falling off the radar of overall employment in India they shall be also disappear from the magic accounting of the GDP as shall Muslims and Dalits servicing and nourishng a vital traditional export business and the voices of disagreement and discontent shall not be heard in the clamour of a Shining India.

The narrative of the GDP number is a plot with no people in it. The GDP should have been a reflection of the welfare of a people not of the abstract notion of an economy’s “output”. That is what Simon Kuznets wanted the GDP to be: a metric of welfare. But post-war capitalism and globalization had other plans, fresh converts to the idea that production of materiality alone counted; a materiality stripped of ethical concerns for humanity and nature, for future generations, for the weak and dispossessed for the thinker and the street singer—unless the song was recorded and marketed.

The GDP does not consider people as living, thinking, dreaming suffering, hungry, disenfranchised human beings unless their actions result in the production of commodities that are marketable and therefore computable by the statisticians of the GDP calculus: which would be fine if it rested its case, or was made to remain as a mere metric of stuff in the national warehouses. But by becoming or having been made into a metonym of national prosperity it does something profoundly totalitarian: it creates a narrative of National State power and wealth. And the people don’t count—except as commodities.

“Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”Robert F. Kennedy.

********

Notes: BT:https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/india-real-gdp-growth-fy20-below-5-revival-steps-take-time-filter-through-economy-ihs-markit/story/391694.html ET:https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/indias-gdp-growth-hits-over-6-year-low-heres-how-analysts-reacted/articleshow/70912164.cms?from=mdr Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, Jean-Paul Fitoussi:Mis-Measuring Our Lives, Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up. Ist Indian Edition.Bookwell Publications. New Delhi. 2010 Dirk Philipsen: The Little Big Number. How The GDP Came to Rule the World and What to do About.Princeton University Press. 2015 David Pilling: The Growth Delusion. The Wealth and Well Being of Nations Blooomsbury. India 2018 Watch David Piling on his book at the LSE London 2018

Ronny Sen pic: ©Ronny Sen from End of Time. Nazar Photography Monographs 04.

Further Select References:

India and the Environment: https://www.wwfindia.org/news_facts/wwf_publications/living_planet_report_2018/

Ronny Sen: Visions of An Apocalypse: The End of Time.

Ehsan Masood: The Great Invention: The Story of GDP and The Making and Unmaking of the Modern World Pegasus. 2016

Leave a Reply