Prologue to Huxley’s “A Note on Gandhi”

“This most practical of men…”

What tribute could have been as apposite as Aldous Huxley’s, just a year after the leader had fallen prey to his assassin’s bullets? Right at the outset the author of Brave New World locates India’s problematic in Gandhian terms: freedom for Indians meant the appropriation of the trappings of power, of the chains of the Nation-state. Drawing on Hind Swaraj, Huxley finds India rejecting the tiger of colonialism but adopting its tigerish nature. As Mithi Mukherjee reminded us in her book, India in the Shadows of Empire, India had embraced the colonial discourse and apparatus it had fought against; only Gandhi had opposed the adoption of the Nation-State by his followers because he sensed that it would turn them into the very ‘tigers’ they had been ‘oppressed by.

Huxley finds that weaponising inevitable “in a world organized for war.” For an author who had seen dystopia creeping over the horizon and savaged it in Brave New World, Huxley was looking at the smoke signals on the horizon, heralding a permanent state of war and military tension since the end of the hot World War II and the immediate ascension of the grey mists of the Cold War. Nation-States had become metonyms for armaments and war. Like it or not, the “ex-prisoners and ex-pacifists” found themselves inheriting “the instruments of violent coercion” and turned into “Jailers and generals.” Frames of reference matter, contexts define one’s actions and nationalist “postulates” that underlined the freedom struggles all around the world foretold “armaments, war and an increasing centralization of political and economic power.”

Huxley remained pessimistic about the capacity of future generations to change this nationalist discourse. But then he remembers Gandhi who had given us a vision of another world; the author of the most dystopic novel finds a redemptive ideal in his own time, in the lifeless figure of Gandhi gunned down by nationalist bullets. And why wouldn’t he? The fiction of Brave New World held up the truth of a dawning reality. Its exposure of hegemonic power based not on muscle power, the boot on the human face, as Orwell had described in his own dystopian novel 1984, but on a frightening use of science and technology by State apparatuses to promote a heedless satiation, was a cautionary that no one would heed. And why would they? Capitalism and market driven consumerism was the answer to the deprivations of world wars, the Depression; its promise lay in its nascence. By the end of the Second World War, in fact thanks to it, capitalism’s wheels were gathering speed; the age of consumption based prosperity was already tinting the sky roseate. In our neck of the woods, the promise of freedom for desire-satiation would allow few Indians to lend an ear to Gandhi’s misgivings of the nation-state and self-indulgence.

Huxley foresaw the future in the budding state of free India; in it’s incipience he saw Gandhi’s failure to “modify the essentially tigerish nature of nationalism as such.”

Pessimist he may have been but not despairing. The author of a savagely dystopic novel with no redemptive endings, views Gandhi a “dreamer” with his “feet firmly planted on the ground”; Huxley still pins his hopes on a time when society will find that this “most practical of men” had got a measure of man’s place in the world–a creature of “no great size” and for the most part of “modest abilities” yet imbued with an “infinite capacity for spiritual progress.” Most nationalist leaders would have agreed about man’s limited qualities but would have tended to the view that technology and centralized statist power could turn that creature into a superhuman being. For such power brokers and seekers eager to mould India in the image of a dubious secularized modernity the “infinities of a spiritual realization” were orthodoxies best discounted, denied.

Did Huxley find in Gandhi then the antidote to the dystopic world he had imagined and created, a brave new world in which people love servitude, where self-indulgence keeps the wheels of industry turning and “soma” is “Christianity without tears.” The dystopia he had painted so presciently was an artistic leap into the future, into the way we were destined to live and are living. Did he find in Gandhi’s philosophy, in the utopia he was painting for an India of his dreams, the wisdom for that future he would create with words on the pages of his masterful work?

The vectors of the new nation-state Huxley foresaw on the eve of India’s tryst with destiny were the foundations for the Brave New World: a muscular, armed nation-State; centralized economic and political power, heavy industrialization, prosperity “and also, no doubt (as in all other highly industrialized states) a rising incidence of neuroses and incapacitating psychosomatic disorders”

In Gandhi’s answer to the violence of the nation-state pivoting on technology and centralized economic/political power and the consequent alienation of the individual from those qualities that make her human, Huxley found an empathic resonance. “Democracy must mean decentralization in which localized groups can have say in self-governing, in finding love and personal relationships and Charity, in the “Pauline sense of the word.” Not almsgiving, that Gandhi decried and condemned but the generosity of agape, ‘disinterested’ love.

Like other critics of Gandhian economic decentalization Huxley demurs from an endorsement of what he thinks Gandhi condemned: all forms of power-driven machinery. Perhaps Gandhi’s emphasis on the charkha ought to be considered a way of emphasizing the individual’s autonomy and agency from the alienating power of the machine. Who can deny that the robot represents the logical extension, the end of the alienation process that began in the nineteenth century, rendering humans redundant?

After likening some of the ideas of Gandhi to Thomas Jefferson’s visions for America as a decntralzied federation, Huxley gets to the heart of the most unique worldview in history that would also make history across the globe even if it was to be forgotten in the land of its birth: Gandhi’s insistence on the political as ethical and moral praxis. The Beacon

*****

![]()

“A NOTE ON GANDHI”

Aldous Huxley

G

andhi’s body was borne to the pyre on a weapons carrier. There were tanks and armoured cars in the funeral procession, and detachments of soldiers and police. Circling overhead were fighter planes of the Indian Air Force. All these instruments of violent coercion were paraded in honor of the apostle of non-violence and soul force. It is an inevitable irony; for, by definition, a nation is a sovereign community possessing the means to make war other sovereign communities. Consequently, a national tribute to any individual—even if that individual be a Gandhi—must always and necessarily take the form of a play of military and coercive might.

Nearly forty years ago, in his Hind Swaraj, Gandhi asked his compatriots what they meant by such phrases as “Self-Government” and “Home Rule.” Did they merely want a social organization of the kind then prevailing, but in the hands, not of English, but of Indian politicians and administrators? If so, their wish was merely to get rid of the tiger, while carefully preserving for themselves its tigerish nature. Or were they prepared to mean by “swaraj” what Gandhi himself meant by it—the realization of the highest potentialities of Indian civilization by persons who had learnt to govern themselves individually and to undertake collective action in the spirit and by the methods of satyagraha?

In a world organized for war it was hard, it was all but impossible, for India to choose any other nations. The men and women who had led the non-violent struggle against the foreign oppressor suddenly found themselves in control of a sovereign state equipped with the instruments of violent coercion. The ex-prisoners and ex-pacifists were transformed overnight, whether they liked it or not, into jailers and generals.

The historical precedents offer little ground for optimism. When the Spanish colonies achieved their liberty as independent nations, what happened? Their new rulers raised armies and went to war with one another. In Europe, Mazzini preached a nationalism that was idealistic and humanitarian. But when the victims of oppression won their freedom, they soon become aggressors and imperialists on their own account. It could scarcely have been otherwise. For the frame of reference within which one does one’s thinking, determines the nature of the conclusions, theoretical and practical, at which one arrives. Starting from Euclidean postulates, one cannot fail to reach the conclusion that the angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles. And starting from nationalistic postulates, one cannot fail to arrive at armaments, war and an increasing centralization of political and economic power.

Basic patterns of thought and feeling cannot be quickly changed. It will probably be a long time before the nationalistic frame of reference is replaced by a set of terms in which men can do their political thinking non-nationalistically. But meanwhile, technology advances with undiminished rapidity. It would normally take two generations, perhaps even two centuries, to overcome the mental inertia created by the ingrained habit of thinking nationalistically. Thanks to the application of scientific discoveries to the arts of war, we have only about two years in which to perform this herculean task. That it actually will be accomplished in so short a time seems, to say the least, exceedingly improbable.

Gandhi found himself involved in a struggle for national independence; but he always hoped to be able to transform the nationalism in whose name he was fighting— to transform it first by the substitution of satyagraha for violence and second, by the application to social and economic life of the principles of decentralization. Up to the present, his hopes have not been realized. The new nation resembles other nations inasmuch as it is equipped with the instruments of violent coercion. Moreover, the plans for its economic development aim at the creation of a highly industrialized state, complete with great factories under capitalistic or governmental control, increasing centralization of power, a rising standard of living and also, no doubt (as in all other highly industrialized states) a rising incidence of neuroses and incapacitating psychosomatic disorders. Gandhi succeeded in ridding his country of the alien tiger; but he failed in his attempts to modify the essentially tigerish nature of nationalism as such.

Must we therefore despair? I think not. The pressure of fact is painful and, we may hope, finally irresistible. Sooner or later it will be realized, that this dreamer had his feet firmly planted on the ground, that this idealist was the most practical of men. For Gandhi’s social and economic ideas are based upon a realistic appraisal of man’s nature and the nature of his position in the universe. He knew, on the one hand, that the cumulative triumphs of advancing organization and progressive technology cannot alter the basic fact that man is an animal of no great size and, in most cases, of very modest abilities. And, on the other hand, he knew that these physical and intellectual limitations are compatible with a practically infinite capacity for spiritual progress. The mistake of most of Gandhiji’s contemporaries was to suppose that technology and organization could turn the petty human animal into a superhuman being and could provide a substitute for the infinities of a spiritual realization, whose very existence it had become orthodox to deny.

For this amphibious being on the borderline between the animal and the spiritual, what sort of social, political and economic arrangements are the most appropriate? To this question, Gandhi gave a simple and eminently sensible answer. Men, he said, should do their actual living and working in communities of a size commensurate with their bodily and mental stature, communities small enough to permit of genuine self-government and the assumption of personal responsibilities, federated into larger units in such a way that the temptation to abuse great power should not arise. The larger a democracy grows, the less real becomes the rule of the people and the smaller the say of individuals and localized groups in deciding their own destinies. Moreover love, and affection are essentially personal relationships. Consequently, it is only in small groups that Charity, in the Pauline sense of the word, can manifest itself. Needless to say, the smallness of the group in no way guarantees the emergence of Charity between its members; but it does, at least, create the possibi1ity of Charity. In a large, undifferentiated group, the possibility does not even exist, for the simple reason that most of its members cannot, in the nature of things, have personal relations with one another. “He that loveth not knoweth not God, for God is love.” Charity is at once the means and the end of spirituality. A social organization, so contrived that, over a large field of human activity, it makes the manifestation of Charity impossible, is obviously a bad organization.

Decentralization in economics must go hand in hand with decentralization in politics. Individuals, families and small co-operative groups should own the land and instruments necessary for their own subsistence and for supplying a local market. Among these necessary instruments of production, Gandhi wished to include only hand tools. Other decentralists—and I for one would agree with them—can see no objection to power-driven machinery provided it be on a scale commensurate with individuals and small co-operative groups. The making of these power-driven machines would, of course, require to be carried out in large, highly specialized factories. To provide individuals and small groups with the mechanical means of creating abundance, perhaps one-third of all production would have to be carried out in such factories. This does not seem too high a price to pay for combining decentralization with mechanical efficiency. Too much mechanical efficiency is the enemy of liberty because it leads to regimentation and the loss of spontaneity. Too little efficiency is also the enemy of liberty, because it results in chronic poverty and anarchy. Between the two extremes, there is a happy mean, a point at which we can enjoy the most important advantages of modem technology at a social and psychological price which is not excessive.

It is interesting to recall that, if the great apostle of Western democracy had had his way, America would now be a federation, not merely of forty-eight states, but of many thousands of self-governing wards. To the end of a long life, Jefferson tried to persuade his compatriots to decentralize their government to the limit. “As Cato concluded every speech with the words, Carthago delenda est, so do I every opinion with the injunction, ‘Divide the counties into wards.’” His aim, in the words of Professor John Dewey, “was to make the wards ‘little republics, with a warden at the head of each, for all those concerns which being under their eye, they could better manage than the larger republics of the county or State’… In short, they were to exercise directly, with respect to their own affairs, all the functions of government, civil and military. In addition, when any important wider matter came up for decision, all wards would be called into meeting on the same day, so that the collective sense of the whole people would be produced. The plan was not adopted. But it was an essential part of Jefferson’s political philosophy.” And it was an essential part of his political philosophy, because that philosophy, like Gandhi’s philosophy, was essentially ethical and religious. In his view, all human beings are born equal, inasmuch as all are the children of God. Being the children of God, they have certain Tights and certain responsibilities — rights and responsibilities which can be exercised most effectively within a hierarchy of self-governing republics, rising from the ward through the State to the Federation.

“Other days,” writes Professor Dewey, “bring other words and other opinions behind the words that are used. The terms in which Jefferson expressed his belief in the moral criterion for judging all political arrangements and his belief that republican institutions are the only ones that are legitimate, are not now current. It is doubtful, however, whether defence of democracy against the attacks to which it is subjected does not depend upon taking, once more, the position Jefferson took about its moral basis and purpose, even though we have to find another set of words in which to formulate the moral ideal served by democracy. A renewal of faith in common human nature, in its potentialities in general and in its power in particular, to respond to reason and truth, is a surer bulwark against totalitarianism than in demonstration of material success or devout worship of special legal and political forms.”

Gandhi, like Jefferson, thought of politics in moral and religious terms. That is why his proposed solutions bear so close a resemblance to those proposed by the great American. That he went further than Jefferson — for example, in recommending economic as well as political decentralization and in advocating the use of satyagraha in place of the ward’s “elementary exercises of militia”—is due to the fact that his ethic was more radical and his religion more profoundly realistic than Jefferson’s. Jefferson’s plan was not adopted; nor was Gandhi’s. So much the worse for us and our descendants.

First published January 30 2018

Title: Reflections on Gandhi

![]()

Prologue to Orwell’s “Reflections…”

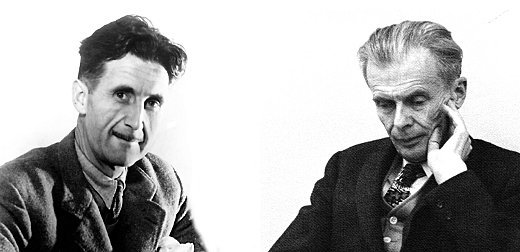

In January 1949, a year after Gandhi was shot, George Orwell wrote an essay for The Partisan Review on Gandhi in which he assesses the man and his work in the context of a devastating world war, the Holocaust, India’s independence and the retreat of British colonialism from south Asia. Reflections on Gandhi is significant for what it seems to tell us about the author of “Animal Farm” and “1984” rather than Gandhi.

We have learnt, thanks to Francis Stoner Saunders compelling work. “The Cultural Cold War” that the The Partisan Review was part of a campaign by the CIA to penetrate and denigrate the Soviet Union and communism. But the author of the epic novel about totalitarianism, wherever it might attempt to crush the individual spirit, could not have known that. But he could have known, or at least should have known, that India’s freedom struggle was closely tied to the “saint” he finds “aesthetically” distasteful.

We get an ‘Orientalist’ reading of “a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat” fantasizing about “shaking empires by sheer spiritual power” faced with the choice of stepping onto the hurly-burly of politics with their “coercion and fraud.” Orwell’s “naked old man” analogy sounds fairly reminiscent of Winston Churchill’s thundering sneer at the “fakir” “…striding half naked up the steps of the Viceregal Palace…”

Orwell sees Gandhi with western eyes saintliness and sainthood as anti-human. He admits that Gandhi himself never claimed to be a saint yet he draws a distinction between saintliness and humanism to tell us that Gandhi’s “aims were anti-human and reactionary.” Gandhi’s autobiography, (My Experiments with Truth) that Orwell talks about makes an impression on him; the man does not. Orwell himself lived rather ascetically partly out of necessity but also, when he came into money, as an indictment of bourgeois values. In the homespun cloth he sniffs at, he cannot see the elements of a civilizational struggle for alternate and collective lifestyles—he sees authoritarianism of saintliness…

Gandhi represents to Orwell the renunciate/saint condemning human foibles and weaknesses. But Orwell himself was contemptuous of the middle classes; the Socialists among them came in for some drubbing. “The worst advertisement for Socialism” he said, “is its adherents…”He called W.H. Auden a “gutless Kipling” In The Road to Wigan Pier, he savages the “fruit juice-drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex-maniac…’Nature-Cure’ quack, pacifist, feminist in England” who are drawn to Socialism and Communism. Fruit-drinker, sandal-wearer, vegetarian…is that why he had an “aesthetic distaste” for Gandhi?

Orwell has little patience for non-violent struggles, Satyagraha as a form of mass resistance to oppression; if it worked in India it was thanks to the British who were more accommodating than say, the Soviet state would have been. Perhaps Orwell had expended all his intellectual and emotional fury and even helplessness about totalitarianism onto the pages of 1984. Close to death himself on the Isle of Jura he took a more pessimistic view of human potential and agency; and in any case Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights movement were some two decades away.

So Orwell personalizes his subject. Gandhi’s “phenomenal piety”, his personal courage, his lack of color prejudice draws grudging admiration from a writer/public intellectual who has just admitted disdain for Gandhi’s aims; but he distances these qualities from their bearing on and rootedness in India’s mass movements however tenuous they might have been.

For Orwell, freedom came to India on account of a Labour government in power; had Churchill still been in power things would have been different. The Orientalist discourse cannot help dismiss the uniqueness of a freedom struggle grounded in any other terms than the western one of power-politics expediency. For Orwell, Gandhi’s uniqueness remains a personalized one also evident in his immense courage to confront awkward questions that even pacifists and socialists tiptoed around. And all that Orwell is willing to admit is that as a politician, Gandhi left behind a “clean smell.” The Beacon

*****

“Reflections on Gandhi”

George Orwell

S

aints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases. In Gandhi’s case the questions one feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity — by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power — and to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud? To give a definite answer one would have to study Gandhi’s acts and writings in immense detail, for his whole life was a sort of pilgrimage in which every act was significant. But this partial autobiography, which ends in the nineteen-twenties, is strong evidence in his favor, all the more because it covers what he would have called the unregenerate part of his life and reminds one that inside the saint, or near-saint, there was a very shrewd, able person who could, if he had chosen, have been a brilliant success as a lawyer, an administrator or perhaps even a businessman.

At about the time when the autobiography first appeared I remember reading its opening chapters in the ill-printed pages of some Indian newspaper. They made a good impression on me, which Gandhi himself at that time did not. The things that one associated with him — home-spun cloth, “soul forces” and vegetarianism — were unappealing, and his medievalist program was obviously not viable in a backward, starving, over-populated country. It was also apparent that the British were making use of him, or thought they were making use of him. Strictly speaking, as a Nationalist, he was an enemy, but since in every crisis he would exert himself to prevent violence — which, from the British point of view, meant preventing any effective action whatever — he could be regarded as “our man”. In private this was sometimes cynically admitted. The attitude of the Indian millionaires was similar. Gandhi called upon them to repent, and naturally they preferred him to the Socialists and Communists who, given the chance, would actually have taken their money away. How reliable such calculations are in the long run is doubtful; as Gandhi himself says, “in the end deceivers deceive only themselves”; but at any rate the gentleness with which he was nearly always handled was due partly to the feeling that he was useful. The British Conservatives only became really angry with him when, as in 1942, he was in effect turning his non-violence against a different conqueror.

But I could see even then that the British officials who spoke of him with a mixture of amusement and disapproval also genuinely liked and admired him, after a fashion. Nobody ever suggested that he was corrupt, or ambitious in any vulgar way, or that anything he did was actuated by fear or malice. In judging a man like Gandhi one seems instinctively to apply high standards, so that some of his virtues have passed almost unnoticed. For instance, it is clear even from the autobiography that his natural physical courage was quite outstanding: the manner of his death was a later illustration of this, for a public man who attached any value to his own skin would have been more adequately guarded.

Again, he seems to have been quite free from that maniacal suspiciousness which, as E. M. Forster rightly says in A Passage to India, is the besetting Indian vice, as hypocrisy is the British vice. Although no doubt he was shrewd enough in detecting dishonesty, he seems wherever possible to have believed that other people were acting in good faith and had a better nature through which they could be approached. And though he came of a poor middle-class family, started life rather unfavorably, and was probably of unimpressive physical appearance, he was not afflicted by envy or by the feeling of inferiority.

Color feeling when he first met it in its worst form in South Africa, seems rather to have astonished him. Even when he was fighting what was in effect a color war, he did not think of people in terms of race or status. The governor of a province, a cotton millionaire, a half-starved Dravidian coolie, a British private soldier were all equally human beings, to be approached in much the same way. It is noticeable that even in the worst possible circumstances, as in South Africa when he was making himself unpopular as the champion of the Indian community, he did not lack European friends.

W

ritten in short lengths for newspaper serialization, the autobiography is not a literary masterpiece, but it is the more impressive because of the commonplaceness of much of its material. It is well to be reminded that Gandhi started out with the normal ambitions of a young Indian student and only adopted his extremist opinions by degrees and, in some cases, rather unwillingly. There was a time, it is interesting to learn, when he wore a top hat, took dancing lessons, studied French and Latin, went up the Eiffel Tower and even tried to learn the violin — all this was the idea of assimilating European civilization as thoroughly as possible. He was not one of those saints who are marked out by their phenomenal piety from childhood onwards, nor one of the other kind who forsake the world after sensational debaucheries. He makes full confession of the misdeeds of his youth, but in fact there is not much to confess. As a frontispiece to the book there is a photograph of Gandhi’s possessions at the time of his death. The whole outfit could be purchased for about 5 pounds, and Gandhi’s sins, at least his fleshly sins, would make the same sort of appearance if placed all in one heap. A few cigarettes, a few mouthfuls of meat, a few annas pilfered in childhood from the maidservant, two visits to a brothel (on each occasion he got away without “doing anything”), one narrowly escaped lapse with his landlady in Plymouth, one outburst of temper — that is about the whole collection. Almost from childhood onwards he had a deep earnestness, an attitude ethical rather than religious, but, until he was about thirty, no very definite sense of direction. His first entry into anything describable as public life was made by way of vegetarianism. Underneath his less ordinary qualities one feels all the time the solid middle-class businessmen who were his ancestors. One feels that even after he had abandoned personal ambition he must have been a resourceful, energetic lawyer and a hard-headed political organizer, careful in keeping down expenses, an adroit handler of committees and an indefatigable chaser of subscriptions.

His character was an extraordinarily mixed one, but there was almost nothing in it that you can put your finger on and call bad, and I believe that even Gandhi’s worst enemies would admit that he was an interesting and unusual man who enriched the world simply by being alive. Whether he was also a lovable man, and whether his teachings can have much for those who do not accept the religious beliefs on which they are founded, I have never felt fully certain.

Of late years it has been the fashion to talk about Gandhi as though he were not only sympathetic to the Western Left-wing movement, but were integrally part of it. Anarchists and pacifists, in particular, have claimed him for their own, noticing only that he was opposed to centralism and State violence and ignoring the other-worldly, anti-humanist tendency of his doctrines. But one should, I think, realize that Gandhi’s teachings cannot be squared with the belief that Man is the measure of all things and that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have. They make sense only on the assumption that God exists and that the world of solid objects is an illusion to be escaped from.

It is worth considering the disciplines which Gandhi imposed on himself and which — though he might not insist on every one of his followers observing every detail — he considered indispensable if one wanted to serve either God or humanity. First of all, no meat-eating, and if possible no animal food in any form. (Gandhi himself, for the sake of his health, had to compromise on milk, but seems to have felt this to be a backsliding.) No alcohol or tobacco, and no spices or condiments even of a vegetable kind, since food should be taken not for its own sake but solely in order to preserve one’s strength. Secondly, if possible, no sexual intercourse. If sexual intercourse must happen, then it should be for the sole purpose of begetting children and presumably at long intervals. Gandhi himself, in his middle thirties, took the vow of brahmacharya, which means not only complete chastity but the elimination of sexual desire. This condition, it seems, is difficult to attain without a special diet and frequent fasting. One of the dangers of milk-drinking is that it is apt to arouse sexual desire. And finally — this is the cardinal point — for the seeker after goodness there must be no close friendships and no exclusive loves whatever.

Close friendships, Gandhi says, are dangerous, because “friends react on one another” and through loyalty to a friend one can be led into wrong-doing. This is unquestionably true. Moreover, if one is to love God, or to love humanity as a whole, one cannot give one’s preference to any individual person. This again is true, and it marks the point at which the humanistic and the religious attitude cease to be reconcilable. To an ordinary human being, love means nothing if it does not mean loving some people more than others. The autobiography leaves it uncertain whether Gandhi behaved in an inconsiderate way to his wife and children, but at any rate it makes clear that on three occasions he was willing to let his wife or a child die rather than administer the animal food prescribed by the doctor. It is true that the threatened death never actually occurred, and also that Gandhi — with, one gathers, a good deal of moral pressure in the opposite direction — always gave the patient the choice of staying alive at the price of committing a sin: still, if the decision had been solely his own, he would have forbidden the animal food, whatever the risks might be. There must, he says, be some limit to what we will do in order to remain alive, and the limit is well on this side of chicken broth. This attitude is perhaps a noble one, but, in the sense which — I think — most people would give to the word, it is inhuman.

The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one’s love upon other human individuals.

No doubt alcohol, tobacco, and so forth, are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid. There is an obvious retort to this, but one should be wary about making it. In this yogi-ridden age, it is too readily assumed that “non-attachment” is not only better than a full acceptance of earthly life, but that the ordinary man only rejects it because it is too difficult: in other words, that the average human being is a failed saint. It is doubtful whether this is true. Many people genuinely do not wish to be saints, and it is probable that some who achieve or aspire to sainthood have never felt much temptation to be human beings. If one could follow it to its psychological roots, one would, I believe, find that the main motive for “non-attachment” is a desire to escape from the pain of living, and above all from love, which, sexual or non-sexual, is hard work. But it is not necessary here to argue whether the other-worldly or the humanistic ideal is “higher”. The point is that they are incompatible. One must choose between God and Man, and all “radicals” and “progressives”, from the mildest Liberal to the most extreme Anarchist, have in effect chosen Man.

However, Gandhi’s pacifism can be separated to some extent from his other teachings. Its motive was religious, but he claimed also for it that it was a definitive technique, a method, capable of producing desired political results. Gandhi’s attitude was not that of most Western pacifists. Satyagraha, first evolved in South Africa, was a sort of non-violent warfare, a way of defeating the enemy without hurting him and without feeling or arousing hatred. It entailed such things as civil disobedience, strikes, lying down in front of railway trains, enduring police charges without running away and without hitting back, and the like. Gandhi objected to “passive resistance” as a translation of Satyagraha: in Gujarati, it seems, the word means “firmness in the truth”. In his early days Gandhi served as a stretcher-bearer on the British side in the Boer War, and he was prepared to do the same again in the war of 1914-18.

Even after he had completely abjured violence he was honest enough to see that in war it is usually necessary to take sides. He did not — indeed, since his whole political life centred round a struggle for national independence, he could not — take the sterile and dishonest line of pretending that in every war both sides are exactly the same and it makes no difference who wins.Nor did he, like most Western pacifists, specialize in avoiding awkward questions.

In relation to the late war, one question that every pacifist had a clear obligation to answer was: “What about the Jews? Are you prepared to see them exterminated? If not, how do you propose to save them without resorting to war?” I must say that I have never heard, from any Western pacifist, an honest answer to this question, though I have heard plenty of evasions, usually of the “you’re another” type. But it so happens that Gandhi was asked a somewhat similar question in 1938 and that his answer is on record in Mr. Louis Fischer’s Gandhi and Stalin. According to Mr. Fischer, Gandhi’s view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly. One has the impression that this attitude staggered even so warm an admirer as Mr. Fischer, but Gandhi was merely being honest. If you are not prepared to take life, you must often be prepared for lives to be lost in some other way. When, in 1942, he urged non-violent resistance against a Japanese invasion, he was ready to admit that it might cost several million deaths.

A

t the same time there is reason to think that Gandhi, who after all was born in 1869, did not understand the nature of totalitarianism and saw everything in terms of his own struggle against the British government. The important point here is not so much that the British treated him forbearingly as that he was always able to command publicity. As can be seen from the phrase quoted above, he believed in “arousing the world”, which is only possible if the world gets a chance to hear what you are doing. It is difficult to see how Gandhi’s methods could be applied in a country where opponents of the regime disappear in the middle of the night and are never heard of again.Without a free press and the right of assembly, it is impossible not merely to appeal to outside opinion, but to bring a mass movement into being, or even to make your intentions known to your adversary.

Is there a Gandhi in Russia at this moment? And if there is, what is he accomplishing? The Russian masses could only practise civil disobedience if the same idea happened to occur to all of them simultaneously, and even then, to judge by the history of the Ukraine famine, it would make no difference. But let it be granted that non-violent resistance can be effective against one’s own government, or against an occupying power: even so, how does one put it into practise internationally? Gandhi’s various conflicting statements on the late war seem to show that he felt the difficulty of this. Applied to foreign politics, pacifism either stops being pacifist or becomes appeasement. Moreover the assumption, which served Gandhi so well in dealing with individuals, that all human beings are more or less approachable and will respond to a generous gesture, needs to be seriously questioned. It is not necessarily true, for example, when you are dealing with lunatics. Then the question becomes: Who is sane? Was Hitler sane? And is it not possible for one whole culture to be insane by the standards of another? And, so far as one can gauge the feelings of whole nations, is there any apparent connection between a generous deed and a friendly response? Is gratitude a factor in international politics?

These and kindred questions need discussion, and need it urgently, in the few years left to us before somebody presses the button and the rockets begin to fly. It seems doubtful whether civilization can stand another major war, and it is at least thinkable that the way out lies through non-violence.

It is Gandhi’s virtue that he would have been ready to give honest consideration to the kind of question that I have raised above; and, indeed, he probably did discuss most of these questions somewhere or other in his innumerable newspaper articles.

One feels of him that there was much he did not understand, but not that there was anything that he was frightened of saying or thinking. I have never been able to feel much liking for Gandhi, but I do not feel sure that as a political thinker he was wrong in the main, nor do I believe that his life was a failure.

It is curious that when he was assassinated, many of his warmest admirers exclaimed sorrowfully that he had lived just long enough to see his life work in ruins, because India was engaged in a civil war which had always been foreseen as one of the byproducts of the transfer of power. But it was not in trying to smooth down Hindu-Moslem rivalry that Gandhi had spent his life. His main political objective, the peaceful ending of British rule, had after all been attained. As usual the relevant facts cut across one another. On the other hand, the British did get out of India without fighting, an event which very few observers indeed would have predicted until about a year before it happened. On the other hand, this was done by a Labour government, and it is certain that a Conservative government, especially a government headed by Churchill, would have acted differently. But if, by 1945, there had grown up in Britain a large body of opinion sympathetic to Indian independence, how far was this due to Gandhi’s personal influence? And if, as may happen, India and Britain finally settle down into a decent and friendly relationship, will this be partly because Gandhi, by keeping up his struggle obstinately and without hatred, disinfected the political air?

That one even thinks of asking such questions indicates his stature. One may feel, as I do, a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi, one may reject the claims of sainthood made on his behalf (he never made any such claim himself, by the way), one may also reject sainthood as an ideal and therefore feel that Gandhi’s basic aims were anti-human and reactionary: but regarded simply as a politician, and compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!

Notes. Aldous Huxley “A Note on Gandhi”: Excerpted from Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., Mahatma Gandhi: Essays and Reflections on His Life and Work. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing, 1998-ninth enlarged edition—The Swaraj Foundation Text courtesy The Swaraj Foundation. http://www.swaraj.org/huxley.htm George Orwell “Reflections on Gandhi” accessed from: http://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/gandhi/english/e_gandhi

Leave a Reply