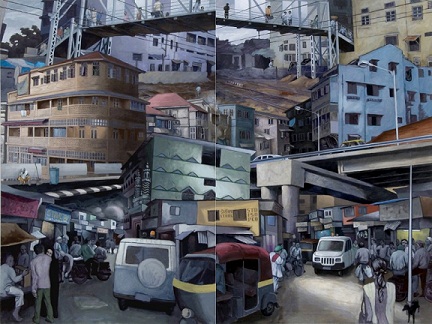

Sudhir Patwardhan. Untitled 2006.

“God forbid that India should take to industrialization after the manner of the West.If an entire nation of 300 million took to similar economic exploitation, it would strip off the world bare like locusts.” M.K. Gandhi

“…an endless feast of grossness” Rabindranath Tagore

U.R. Sane

I

n the run upto the release of its annual The State of the Environment 2019 in Figures report in June this year a day before World Environment Day, the Centre for Science and Environment listed for us a set of environmentally catastrophic states-of -being as markers of an inexorable planetary death spiral created by mindless development fuelled by a blinkered and thoughtless materiality. Among other things the report outlined a dismal state of climate on account of greenhouse gas emissions by the energy sector, principally. There was, notes the report, a 25 per cent increase in GHG emissions in the four years to 2014 with the energy sector responsible for 73 per cent of those emissions. “India continues to bear the brunt of extreme weather events. In 2018, 11 states recorded extreme weather events that claimed 1,425 lives.”

The primacy of the energy sector as the villain of the pieceis also corroborated by the USAID’s factsheet on GHG emissions in India that followed it up with other sectoral villains such as agriculture, industrial processes, land-use change and forestry, and waste. The GHG Platform India, a collective civil society initiatives that calculates such emissions “at a more granular level” has collected between 2005-2013 data that also show the energy sector contributing two-thirds of the emissions followed by industry, agriculture and waste.

While India lags behind the USA and China in such emissions per capita, the sources of the damage to the environment point to more or less the same indicators of “development” be they energy , industry agriculture, transport.

What’s hidden in plain sight, in India China or the USA is the end user of all these production processes. People! When looking for the perpetrators of planetary degradtion, we tend to forget the role that consumption plays in galvanizing the sectors that contribute to the environment’s slow death. The energy sector spouts gases because we demand electricity regardless of how its produced so long as it comes cheap and efficiently; industrial processes produce all those goods from blue jeans to French fries fast cars,smart phones and just about everything we don’t need but desire immeasurably.

So is it possible that people, at any rate consumers with the wherewithal to sink into debt consuming, are also responsible for the planet’s death spiral? And where would most of the consumption demand originate if not from cities?

The Future of Urban Consumption in A 1.5° C World, by ‘C40 Cities A network of 94 cities’ released on World Environment Day June 5 this year, offers staggering facts about the way we, as consumers have been active accessories in the destruction of the environment.

As if to ease us into the pain of self-discovery:

“Cities drive the global economy and urban decisions have an impact well beyond city boundaries.” The report therefore considers the greenhouse gas (GHG emissions from urban consumption of “building materials, food, clothing & textiles, private transport, electronics & household appliances, as well as private aviation travel.”

“When a product or service is bought by an urban consumer in a C40 city, resource extraction, manufacturing and transportation have already generated emissions along every link of a global supply chain. Together these consumption-based emissions add up to a total climate impact that is approximately 60% higher than production-based emissions.”

That pair of jeans–a marker of our self-absorption and engagement with modernity–worn by actors prancing around trees and activists protesting the felling of them is a significant contributor to the worsening climate. Its impact includes GHG emissions that result from growing and harvesting the cotton used for the fabric, the CO2e emitted by the factory where it was stitched together, and the emissions from ships, trucks or planes that transport it to the store you frequent, not to mention the impact of emissions from heating, cooling or lighting the store the jeans were bought in and, the CO2e emitted by washing and drying it before you throw it away for another pair bought at another store in a foreign city you flew to.

With expanding globalization and an insatiable appetite for the “foreign,” the division of labour and international supply chains, cities and urban consumers have a huge impact on emissions beyond their own borders; 85 per cent of the emissions associated with goods and services consumed in C40 cities are generated outside the city; 60 per cent in their own country and 25 per cent from abroad.

So what is to be done? The authors of the report suggest that among other things such as policy initiatives by mayors of cities, urban stakeholders

…can address their full consumption-based emissions by actions on “food; buildings and infrastructure; private transport; aviation; clothing and textiles; and electronics and household appliances”

The authors of the report wish for some sort of restraint or curbs on consumption. As they warn:

“In order to stay within GHG budgets and limit global warming to 1.5° C-the internationally agreed upper limit for a climate sfe future-the average per capita impact of urban consumption in C40 cities must decrease by 50 per cent in 2030 and by 80 per cent in 2050.”

And here’s the thing: without any such action of self-restraint, curbs on “the endless feast of grossness” that Rabindranath Tagore bemoaned, emissions from urban based consumption in those 100 odd C40 cities will double (+87 per cent) in 30 years.

![]()

Source: The Future of Urban Consumption in A 1.5° C World p20

*****

In the late months of 1945, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru exchanged a series of letters, part of what The Beacon termed a ‘culture of conversation.’This epistolary dialogue foregrounded the divergences between the ageing radical visionary and the youthful pragmatic/rationalist statesman. Gandhi’s “intuitive understanding” that began, as Sudhir Chandra noted where “the average modern’s rational comprehension ended virtually flew overNehru’s head. Perhaps Nehru’s rational /modern comprehension was incapable of seeing Gandhi’s visions of swrajya as anything more than instrumentalities that had outlived their purpose. The struggle for Independence was coming to an end; victory was at hand and now a new menu of practical considerations had to take precedence over possibilities that seemed to the “average modern”, impossible. (The End at the Beginning…)

What was Gandhi writing to Nehru about? He started off in simple but stark terms to remind Nehru that there were differences between them that he insisted the public be made aware of–one more example of how he made every attempt to expand the public sphere for policy discourse: “If the difference is fundamental then I feel the public should also be made aware of it. It would be detrimental to our work for Swaraj to keep them in the dark.”

And then Gandhi gets down to his idea of an India-in-the-making

“I am convinced that if India is to attain true freedom and through India the world also, then sooner or later the fact must be recognized that people will have to live in villages, not in towns, in huts not in palaces. Crores of people will never be able to live at peace with one another in towns and palaces. They will then have no recourse but to resort to both violence and untruth…We can realize truth and nonviolence only in the simplicity of village life…”(cited in The End…)

Nehru’s reaction was a modernist’s response: the backward village is exactly what we are trying to escape from: “I do not understand why a village should necessarily embody truth and non¬violence. A village, normally speaking, is backward intellectually and culturally and no progress can be made from a backward environment. Narrow-minded people are much more likely to be untruthful and violent.”

This reaction was to become the defining trope of post-Independent India

Did Nehru misread Gandhi? The ‘ageing anarchist’ had not been talking of a real village, the village extant as the model for a new India. He was imagining an “ideal” village as a paradigmatic aspiration for free India, a village of his dreams “that is still in my mind.” And in the next sentence he lays down an abiding creed for humanity to live by and fortify belief in agency: “After all, every man lives in the world of his dreams.” And Nehru, he urges “must not imagine that I am envisaging our village life as it is today.”

So what’s the dream or imagined village he outlines?

“My ideal village will contain intelligent human beings. They will not live in dirt and darkness as animals. Men and women will be free and able to hold their own against anyone in the world. There will be neither plague nor cholera nor small pox; no one will be idle, no one will wallow in luxury. Everyone will have to contribute his quota of manual labour. “

Gandhi was imagining a utopia based on self-sufficiency and simplicity where “man should rest content with what are his real needs and become self- sufficient. If he does not have this control he cannot save himself” Only then will truth and non-violence towards all living beings make the world abetter place than it is now.

His utopian vision was not based on “progress” as defined by stages of development; he did not presume a linear movement of human achievements along a temporal scale of development. His ideal village presumed and required human agency, the active and self-conscious will to restraint and simplicity as measures of our commitment to progress as well-being and swrajya through truth and non-violence.

Rabindranath Tagore too condemned more aggressively and graphically,the “endless feast of grossness” that western materialism/nationalism instilled into the subject. For Tagore, nationalism, the State and materialism went hand in hand turning people into an “organized power” perpetrating violence on the self and nature. Tagore denounced the Nation-State as “national carnivals of materialism” a memorable phrase that about sums up Tagore’s perspective on modernity and its malcontented urges

Tagore and Gandhi book-end an episteme that transcends their time and context to become what Rustom Bharucha calls the “wisdom of the future.” Their visions of a good society–simple life, locating the divine in humanity, to know that what is huge is not great, to create the foundations for a way of life in tune with universal humanism in place of the idolatry of nations. and love of “our modest household lamps” and “eternal stars.” IN Gandhi and Tagore’s radical imaginaries we can glimpse pathways to freedom from the shackles of rampant consumerism that traps us in “huge organizations of slavery in the disguise of freedom”and that lead to the ratcheting of the planet’s death screws.

If, dear reader.at this point, after Tagore’s ringing denunciation of gross materialism and the organization of slavery you wish to reach out for your copy of Brave New World, do so. We do not know, at least I do not know, if Aldous Huxley had read Tagore and Gandhi but it is likely that he would not have had the kind of the distaste for Gandhi that George Orwell exhibited. Written in 1932 Huxley’s masterpiece, holds up a mirror to our slavery to gross pleasure-seeking that is disguised as freedom. A savage and prescient attack on modern capitalism’s endless pursuit of pleasure, written, ironically in the midst o the Great Depression, Huxley’s novel also provides, in the context of our environmental catastrophes and the C40 Cities report on rampant urban consumerism as a major source of GHG emissions and climate change,a cautionary warning, a wisdom of the future, if by negative example.

As one of the chief proponents of the World State policy, Mustapha Mond, explains official policy,, “Industrial Civilization is only possible when there is no self-denial. Self-inndulgence upto the very limits is imposed by hygiene and economics. Otherwise the wheels stop turning!”And, “You cannot have a lasting civilization without plenty of vices.” That, has been the precise problem; a problem that both Gandhi and Tagore warned us against.

If Mond-ism is the allegory for modern capitalism and its environmental disasters. Gandhi’s simplicity and Tagore’s ‘freedom of mind, against the slavery of taste, are its antidote.

*****

Dear Reader! Has the penny dropped?

When Gandhi outlined, sketchily but in all its essentials, his imagined village, he was in effect offering Nehru a utopian vision based on human agency. What he was telling Nehru, his favorite ‘son’ and the future Prime Minster of a free India was to dream of a future in which people would realise their real freedom, swrajya, by defining their future as an outcome of their own thoughts and actions. By investing Indians with the challenge of living in simplicity, with self-restraint, by satisfying, as he wrote their real needs, instead of hankering after palaces, Indians would achieve their utopia of truth and non—violence towards all beings, swarjya.

Gandhi therefore wanted to restore agency to the people. They could build the new India, the imagined village, with their deliberate and self-conscious restraint from wanton consumption, from the temptation to exercise violence on the environment, decimate its rivers, trees and wildlife to build their cities (think of Mumbai’s suburbs built over natural waterways or Bengaluru’s lakes).

For Gandhi, the village, like the charkha was a metaphor for a way of life that Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, pinioned to the giant industrial cog, would have yearned for.

But Nehru, as Rustom Bharucha once pointed out, did not quite see Gandhi’s vision as an imaginary; he read it as an endorsement of the backwardness he wanted India to shed. Nehru was a ‘developmentalist’. He believed in the Western, post-Enlightenment epistemology of human progress along a linear trajectory of growth in stages.That notion of progress, in capitalist societies or the former Soviet Union bestowed Time with the power to realize Utopia with the instrumentality of the Nation-State. In such a notion of advancement, taken to be literally a forward march in Time’s capsule, progress comes to be defined not as human possibility but as teleological inevitability.

With ‘progress’ defined as a forward motion on the rails of Time, the epistemology of development hid in plain sight, a paradox. That paradox has been crucial to the operation of capitalism and has also created the environmental disasters that have so far been viewed as necessary fallout of that progress along linear time: collateral damage.

The paradox is central to the discourses of modernity and advancement. Teleological inevitability strips humanity of agency assigning all initiative of human development to the Nation-State and the organized power of capital it corrals and is beholden to. Yet human intervention becomes central to the realisation of Time’s forward march to progress; humans must produce and what is more, consume. Of the two, Consumption acquires paramountcy as the defining trope of human intervention in neo—classical economic discourse and State policy. Consumption marks the limits of human intervention. Either as active collaborators or complicit observers in the act of escalating Consumption , people abet the wanton destruction of what they should preserve, what they would have preserved had they recognized the expropriation of agency by the organized power of the Nation-State, its instrumentalities and discourses.

The hegemonic character of the ‘development’ discourse that turns it into an axiomatic principle works to disguise that usurpation of human agency; its neon-lit carnivals of consumption, or at least the promise of its baubles, dissipate any resistance among the subjects of nation-States to the appropriation of their right to dream and imagine alternate possibilities of fulfilment :the possibilities that Gandhi and Tagore dreamt of; to escape from the dystopia of Brave New Worldwhere “Sensation is all”, and in its stead to dream of an imagined village in which consumption does not kill our environment: to reassert the need for an “examined life.”

******

There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in. Despite the vicious hegemonic spread of the development discourse, embraced by virtually every shade of the mainstream political spectrum, from Radical Left to the Wrathful Right, the cracks show and widen to reveal the broken lights of its outcomes: an apocalyptic vision of the planet’s death swirls. We witness and experience the disasters we have wrought in our endless pursuit of self-satiation and resistance simmers and grows.

The struggle starts with a cognitive leap that shatters the idea of Time as linear. Do we begin to see it as circular? Turning on itself? Intertwined? Certainly an enigma that helps us shape our own possibilities.

“Through the unknown, remembered gate/When the last of the earth left to discover/Is that which was the beginning;” T.S. Eliot.

Resistance pockets to the neo-liberal nightmare of endless consumption and the desecration of our planet are scattered throughout the world but it has some common features: a dismissal of the development discourse, a return to roots that involves a re-discovery of Nature and its bounties that have to be nurtured as sacred not transformed into ‘”value-additions” as commodities for department store shelves: Nurturing not exploiting, building symbiotic relationships with our environment not subduing it to our will, the new forms of resistance lead to new imaginaries that are outcomes of and inspired by, wisdoms of the futureleanrt by digging into memory. Time is bent, molded such that the past becomes the future in the present and many utopias take shape in the imagination as possible alternatives to the degraded present.

Situated in Gadhciroli district of Maharashtra, India, the village of Mendha Lekha is asserting itself as a ‘Community of Beings’ in which grassroots governance and conservation of forests and natural resources define forms of resistance to the depredations of capitalism and market driven policies dictated by the State. The movement in Mendha and many other villages in Gadchiroli was an outcome of a vigorous struggle by local tribals against a series of hydroelectric dams, proposed by the government in the late 1980s. The dams would have submerged large stretches of dense forests and tribal lands, displacing thousands in this region. In 1985, the government shelved the project. Those struggles emboldened the tribals towards self-rule and collective responsibility. [TEAM DO MAKE THIS Title “Community of Beings… ]

Examples of such resistance abound in India and abroad. In Niyamgar hills in the eastern Ghats of Odisha the small community of Dongria Kondh tribals has opposed multinational attempts at bauxite mining below the hills for years. The struggle has received public attention from environmentalists around the world. But more than the struggle itself, their assertion of the sacredness of their forests and lands define their own notions of ‘development’ and well-being’that are not just at odds with the national discourse of development but also threatened by it.

In their edited collection, “Ecologies of Hope and Transformation”Neera Singh, Seema Kulkarrni and Neema Pathak Broome have put together valuable information on the struggles to define new imaginaries in India. They also point to similar struggles from around the world; the ideas of inter-dependence expressed through Ubuntu in South Africa ,the“Occupy movements that sought alternatives to ‘There is No Alternative’. Prominent among inspiring alternatives are indigeneous visions of “living well”through a co-flourishing with others expressed through sumac kawsayor buenvivir in Latin America…” (Ecologies…)

Indigenous peoples around the world, that have been considered backward, primitives who, according to linear Time and the discourse of neo-liberal development, had some way to go before they could claim to be ‘developed’ as consumers of a market driven society are now emerging as the hope of alternate futures from a degraded present. The C40 Cities report outlines a valuable gap in mainstream understanding of what causes GHG emissions. Urban-based consumption without check is to blame.

But focussing on just that ignores the hegemonic sway of capitalist discourse and the “imperialism of categories” by which progress is strung along Linear Time and well-being made a function of unbridled consumption-based consumption.

What the report and so many other well-meaning analyses miss out is that the options for alternatives are not yet exhausted and that the will to dram of alternate futures is not the prerogative of urban dwellers or the well healed in ‘developed regions of the world. The futures are taking shape among the ‘wretched’ of the earth. And why not? They are of the earth and it belongs to them.

“What we call the beginning is often the end/And to make an end is to make a beginning/The end is where we start from.” T.S. Eliot

Notes

–How Green is the Country…

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/how-green-is-the-country-check-out-our-state-of-india-s-environment-report-2019-in-figures-64915

–USAID: Greenhouse gas emissions factsheet: India.https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/greenhouse-gas-emissions-india

By The Numbers: New Emissions Data Quantify India’s Climate Challenge.

https://www.wri.org/blog/2018/08/numbers-new-emissions-data-quantify-indias-climate-challenge

The Future of Urban Consumption in A 1.5° C World. C40 Cities. Headline Report

T.S. Eliot: “Little Gidding” pp 221-222. Collected Poems 1909-1962.Faber and Faber. 1963

-U.R. Sane is a retired acoustical engineer who served in the railways for thirty years but his heart lay elsewhere. He took voluntary retirement and has been travelling around the country listening to conversations in tea stalls, bars, brothels on river banks. He plans to write a book of those conversations as one long sentence without full stops hoping to weave a tapestry of public dissent, disobedience and debate.

Also read related stuff:

Leave a Reply