Murali Sivaramakrishnan

I

n the state of Kerala, three folk-narratives are still popular despite the widespread acceptance of established mainstream Aryan god heads like Vishnu and his avatars; facets of an earlier tribal culture still exist. Although the tribal king, Mahabali, for instance, may not stand divinised at quite the stature of Vishnu, his image is still held dear deep in these parts. Similarly off-springs of Vararuchi and the woman of a lower caste are almost deified and some have specific temples dedicated to them. In this region, brahmin and paraya, high and low, mainstream and tribal, run alongside without barriers: they complement one another in people’s memories.

In Memories Dreams, Reflections, Carl Jung writes with reverence about the manner in which the “oriental mind” could integrate good and evil as “meaningfully contained in nature.”

In India I was principally concerned with the question of the psychological nature of evil. I had been very much impressed by the way this problem is integrated in Indian spiritual life, and I saw it in a new light. .. For the Oriental the problem of morality does not appear to take first place as it does for us. To the Oriental, good and evil are meaningfully contained in nature, and are merely varying degrees of the same thing. (1989; 305)

Despite this ‘Orientalist’ vision of an eminent psychologist, the point is worth noting:in our part of the world where myth and legend, superstition and science, morality and mathematics merge and re-emerge in the modernity of everyday experience, people’s lives are contained and conditioned by their beliefs and memories. Social and political systems are codified and maintained by the cults of the past and their associations–even among intellectually advanced communities such as in Kerala, a state recognized for several socio cultural achievements and advances. Perhaps people can never be completely segregated from the association of their memories, dreams and reflections of the past. To understand these complexities it might not be out of place to re-examine the metaphors of a people’s memory. It would also hold good for us if we were to keep in mind the varying textures of meta-narratives contained within people’s memories–especially in a region like Kerala where the narratives of the folk, the tribal and the mainstream merge. In such a context, binaries of good and evil, high and low, godly and demoniac need rephrasing.

It might help us if we were to begin our journey into the heart of the country by referencing its geographical entry points. Kerala is bounded by the Western Ghats running from coastal Karnataka down to Kanyakumari, and a coastline on the west stretching close to five hundred miles on the Arabian Sea face. As one moves in from the Tamil Nadu plains one can perceive the difference in terrain: lush green land of the blue hills, the land of coconut palms (Keralam also means the land of Kera or palms) and of slow moving backwaters and forty odd rivers that originate in the mountains and run down to the sea—three of these flow eastwards and cut into Tamil Nadu, joining the Cauvery. There is a highway that turns and cuts in from the southern-most tip of India through Nagercoil—this is the land of magic and enchantment, the erstwhile Nanchinadu coterminous with Tamil and Malayalam. (Mala means mountain and alam means the sea, hence Malayalam also refers to the land between the mountain and sea where this language is spoken). On the other hand, if one were to take the road from Coimbatore (erstwhile Kongunad) one enters Kerala through the Palakkad gap. This is the fabled land of kings and is riddled with legends and unique temples, wild-life and folklore. There are a couple of entry points from the northern part of Kerala as well, which would lead us through Malabar (during the British days Malabar was part of the Madras presidency).

If one were to take the leisurely road winding down on the western coast of India from the Konkan, one would enter through Kasara god, the north Malabar region where Kannada and Malayalm mix, the Tulu-nad of the medieval Malayalam heroic songs (vadakkan-pattu). The other is the winding hilly track through either Mercara or through Mysore—one would either enter through Tellicherry or through the Wynad hills with its fabled Tipu Sultan’s Battery. These roads still offer a marvelous experience for the traveler. Driving down from Karnataka, in the early eighties and even nineties, I still recall glorious encounters with wild elephants indulging in their pleasant mud baths, hordes of cheetal drinking from wayside water bodies, large herds of gaur, an occasional solitary leopard, and packs of wild dogs. All these are still not too distant in time because the road winds through three major wildlife sanctuaries—Bandipur in Karnataka, Muthumalai in Tamil Nadu, and Muthanga in Kerala (well known for its Sloth Bear population still extant). The Veerarajpettai—Iritti—Tellicherry road is still good for its picturesque turns and drops.

When Kerala was formed in 1956 (Sreedhara Menon,1967) bringing together the Travancore and Cochin with the Malabar, a large part of what was historically integrated with this region in mind and spirit—the Nanjinad in the extreme south and the Mangalore belt that is now Karnataka- also came to be split away.

But land becomes region in the minds of a people who live in it, and however much we divide it politically and economically into zones and states it little affects the people internally. The power of myth is much more potent than the forces of history and people often choose to live by it.

Kerala is rife with myths and legends, with folklore and tales, its history embedded in its terrain; the region breathes through its memories. A close reading of three formation myths of this region could help us explore the fashioning and maintenance of socio-political power and patterns of its structures.

In the region of myth, class and caste differences might not be too obvious. Nevertheless almost all myths that are popular down to the present day involve the upper and lower classes, because tribal memory is the the prime text, ur memory[1]. The patterning of social and political power, as has been pointed out time and again by sociologists and intellectuals, do harken back to the proto myths of a people’s community formation. Perceptive scholars have argued that any landscape and its cultural history must be seen in terms of a collection of activities, events, and stories that defined the lives of those who lived within it, therefore leaving a piece of themselves behind. The pieces of individuals may be seen in their prehistoric memories…. (Cynthia Wiley,2008;88,89)

One of the most well-known and the earliest of legends associated with the creation of the land mass of Kerala involves Parasurama, the sixth avatar of Lord Vishnu. Mainstream or tribal, this creation-myth has persisted in people’s dreams and narrations, and it surfaces in many a story and poem in the region. In our own times the state itself has aided its continuity by promoting a tourist-friendly image of the land as God’s Own Country! After slaughtering the Kshatriya families, the angry god flung his battle axe over the seas and the land rose up to the point where the axe fell off. What this myth reveals is not only the patterns of the Brahminical order of its origin but also its connection with the battle’s orgies, revenge-motifs, absolute obedience to the patriarchal order of things and the like.

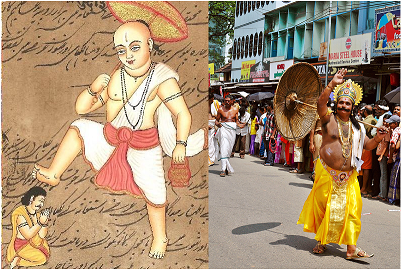

A land that was unstabilized from earliest times but which traces its established ideal through a bloodline.?? The second myth that has given rise to an equally powerful and abiding motif with celebratory status, in people’s memory, is the legend of Onam which is now a sort of national festival. Here is king Mahabali who through his essentially good-natured and honest actions and people-friendly activities arouses the jealousy and wrath of the gods. Probably because he was a people’s king, the myths like to reiterate that Mahabali was a demon-king and thus had to be disposed off. Vishnu takes on the avatar of Vamana, a Brahmin boy and walks into Mahabali’s court. The king is delighted with the visit and offers his hospitality and a boon. Vamana seeks but a tiny space in the kingdom—precisely three paces of land! Mahabali, true to his generous nature unhesitatingly grants the little Brahmin’s request and he desires that a bowl of water be brought so that he can ritually seal the offer. His astute guru Sukracharya counsels him of an impending betrayal and cautions Mahabali, who is already engaged in the required rituals.

Sukracharya turns himself into a seed and blocks the mouth of the vessel. Mahabali pokes him with a stick and the guru loses one eye in the process. Despite all these evil omens and forebodings the king carries out his rituals of generosity. Vamana now reveals his true identity and towers above all and everything. Three steps! With one step he clears all of earth, in the next the skies. “Where should I step next?” he thunders down to the kneeling monarch. “On my head,” whispers the benign king. “So shall it be,” says the lord and kicks Mahabali down into the seventh level of hell, Patala. The cowering subjects plead that they be allowed to see him at least once a year to which Vishnu readily agrees. So each year the people celebrate Onam when Mahabali their beloved king returns to walk amidst them and feast alongside.

The roots of this myth can be traced to fertility cults and tribal rituals. The season following a rich harvest calls for celebration and feasting. Onam is a harvest festival that occurs between the two seasonal monsoons in this part of the world—the south-west and the north-east. Mahabali symbolises people’s hopes and desires, he is the embodiment of goodwill and bliss, an icon of tribal rapture and simple ecstasy; to date tribal songs and tales refer to the iconic image of this native king. By making him return but once in a year it could be that the tribal gods have made sure that the elation of life is marked off in its cyclical process, departure and return, maintaining hope and desire. Thus the creation of a people’s memory of a good old past is effected and sustained. Although there is little evidence that links the myth to any specific tribe or folk narrative, the idea of a good king belonging to the common people capable of provoking the jealousy of a superior god who had to descend to this world in disguise in order to provoke the just king into sanctioning his own destruction is pervasive.

Good and evil comingle here. Mahabali is just and truthful but he belongs to the lower order when the Brahminical sense of Dharma or justice is invoked; thus he is also shown as evil or opposed to the gods. The counter-measure or contrapuntal movement of the narrative continues to make its presence felt in the celebration of Onam (a national or international festival no less!) that celebrates the return of the “evil” King who is the beloved of the people; at the same time Vishnu who incarnated as Vamana is not disowned, renounced or disregarded. Small wonder then that Carl Jung found the paradoxical admixture of good and evil, high and low, demonic and godly, a little difficult to absorb. It is not that the binaries are diffused; they are displaced as well.

Tribal memory is absorbed into mainstream memory and while its power structures are retained through the process of its reintegration into the collective it allows for a free play of all its elements. The annual celebration of Onam as a people’s festival is a reiteration of this process of play.

The third myth is a little more complex in its social structure because it concerns the overlapping of different castes. But here too we can see how the formation of myth functions as a mainstay of a people’s memory harking back countless centuries. One of the major aspects of all mythology is timelessness; myth is placed outside history but its impact on the times is strong and deep.

Asleep under a tree, Vararuchi[1]a Brahmin overhears two gandharvas discussing the prospect of his imminent excommunication from his caste on account of his physical contact with someone of a lower caste. Vararuchi is involved in a desperate search for the most outstanding passage in the Ramayana. The gandharvas in the course of their conversation point out the key passage and also predict that the Brahmin would have to face dire consequences soon. Vararuchi decides to leave his village and wander off to avoid his fate. Can he?

He happens to encounter a woman of lower caste and circumstances force him to have sex with her. Shock follows the day after but what is done cannot be undone and he allows the woman from the paraya caste to accompany him on his aimless travels across the land between the sea and the mountains. Eventually they have twelve offspring and one by one the children are cast out to the care of the elements. As each child is born, Vararuchi’s question to his wife would be: Does the child have a mouth? If so destiny will feed him. Unhappy at discarding her children to the the forest, the luckless woman changes her reply on the birth of the twelfth child she does not wish to abandon: No, she says, the child does not have a mouth and Vararuchi replies, Alright, so be it; the child shall have no mouth.

These twelve children of Vararuchi and the parayi come to be known as Parayi-petta-panthirukulam, or the family of twelve born of the parayi. Each one of them later comes to occupy a significant place in the order of things on account of their miraculous careers, and each one marks out a special space in the minds of the people of Kerala.

This confluence of the upper caste Brahmin and the lower caste parayi constitutes the establishment of a specific power structure amidst the caste-ridden social life of the Malayalee.

The three myths discussed above are formation-myths, they show how a people’s memories are shaped and how a socio-political system also emerges from therein. In the case of the Parasurama myth there is a systemic Brahmin over-dominance of the land and all else is precluded in the arc of the battle-axe. In the second story there is a dual element of deva-asura. The Devas as godly representatives are jealous of the stable wealth of the demons or lower castes and engage the help of the all-powerful Vishnu to depose the good-king Mahabali. Despite the fact that his goodness and kindness are recognised he is depicted as one who cannot continue to be on earth because he probably disrupts the seasonal cycle of bad and good, want and plenitude, chaos and order.

The Parayi-petta Panthirukulam tale underscores the multicultural order of things in this part of the world. Each caste, each community maintains a status by remaining within its purview and thus maintaining the dharma or the social order of things. Nevertheless all trace their origins to Brahminical roots. The tales are always told right, because each tale is a process of telling it right.

The history of tribal in India during the last six decades years or so is replete with stories of forced displacement, land alienation and increasing marginalisation. Their collective memories are encoded in the tales and songs they carry with them and they in turn encode their social fabric. Although in their contemporary version, the three myths may not appear to be “tribal” in their essence what they reveal is the process and traces of marginalisation and displacement from the mainstream. To reread the Parasurama myth is to perceive the rigidity of caste structures that it establishes. The great god who is an avatar of Vishnu is a man-slayer, a Brahmin by birth, but a vanquisher of the warrior tribes. He is instrumental in the creation of God’s Own Country and he is also credited with establishing temples and places of worship in cardinal points along the region. The tribals who were native or indigenous to the land prior to the Aryanisation of the territory still carry the burden of their memory which establishes their own ontology within a power structure that is exercised through a process of hegemony.

Some tales are more pervasive than others and this is the case with the foundation myths or tales of origin. The land and its dwellers are both enmeshed in these tales of collective memory. Myth of course relates to archetypal memories and in this case it is rooted in the tribal mind. The second myth of Mahabali is certainly more ubiquitous than the earlier one, because it is still instilled in the minds of the people as part of their own epistemology—irrespective of caste, creed, religion or belief. The people of Kerala still identify with their beloved monarch despite the fact they do realise that he was held as a demon king in the eyes of Aryavarta. Although Vamana, as an avatar of , Lord Vishnu is not idolised or worshipped as the demon slayer in these parts the people do not reveal any animosity or hatred toward the godhead. This could go a long way toward disclosing the persistence and power of myths and legends that most often subtly determine social structures. The fabric of the people’s memory is closely knit in structure and texture.

Folklore studies in this part of the world from early times had been a special prerogative of inquisitive Anthropologists and Sociologists situating them within their own methodology, until the well-known Kannada linguist A K Ramanujan came out with his collections of Indian folklore narrative and called for a specific focus of attention. When imaginative retelling of folk tales came to be closely examined and studied, new and newer dimensions of understanding the tribal (non-caste organised communities) surfaced. Folklore thus has come to the forefront of tribal community studies. However, even while anthropologists considered folklore only as literature in tune with mere narrative interests, scholars of literature and literary studies came to look upon folklore as culture which occurred within the purview of serous culture studies. Folktales are organic phenomenon and thus an integral part of a people’s culture. Perhaps even these days, for the scientific minded scholar of anthropology, the wealth of folklore remains a mere mirror of a culture not a dynamic factor in it. Only when Tribal Studies evolved as an academic discipline did these folk narratives come to be fore-grounded as constituting a sphere of expression in their own right, and thus proffering a possibility for understanding the socio-political cultural situation of the tribal as such.

The tellers of the folktales are embedded in the narrative and they are inseparable from the tale. A close observation of the folk narratives converging on original or formation myths could reveal the dominant power structures involving the upper classes and the hegemonic maintenance of these structures. The narrators tend to recognise and get reconciled to their subordinate position through the retelling. Thus the narrative maintains a rigid power structure in social terms without exerting any specific effort from outside or even entering into the narrative’s prefabricated mode.

The rich narrative fabric of Kerala is coterminous with people’s lives even in contemporary times. There is hardly any difference between the earliest tribal or folk narratives and their manifestations in the life of the average Malayalee in the present. When tribal and folk studies are undertaken it would be worthwhile to extend the scope to include such remembered narratives as well rather than concentrate only on the tales and songs prevalent amidst the present day tribal communities. These narratives also evidence the continued presence of complementarities rather than binaries. Having said that, one ought to bear ib mind that folk tales currently prevalent among the hill tribes in Kerala also include dominant images of popular Hindu gods and goddesses. Thus the presence of Vishnu and the Goddesses albeit in variant forms like patachchon (creator) or amma bhagavathy (goddess) underscore the hegemony of a pre-established social order and societal structures. When one assays to work across pre-established disciplines, these could function as signs that help interpret and trace those subterranean connections between individual behaviour, tribal memory and communal histories, between past and present, and the abstract ideas of freedom and social harmony.

Notes. [1] “Ur”, used as a prefix (ur-text, ur-memory), means “original or earliest. “Ur” is a German prefix found in several German terms imported into English and used primarily in scholarly and scientific contexts, e.g., “Ursprache” (“sprache” meaning “speech”) or proto-language, and “Urheimat” (“homeland”), the place of origin of a people or language. One of the earliest uses of “ur” in English, as noted by academics, was in the early 20th century in “ur-Hamlet,” the long-lost 16th century play on which Shakespeare supposedly based his version. What could be fascinating is that in Tamil the word Ur means original or native village. 2.See Aitheehyamala, the Garland of Legends. Kottarathil Sankunni (23 March 1855 - 22 July 1937), a Sanskrit-Malayalam scholar who was born in Kottayam in present day Kerala, started documenting these legends and stories available through memory and oral tradition in 1909. They were published in the Malayalam literary magazine, the Bhashaposhini, and were collected in eight volumes and published in the early 20th century. Works Consulted Jung, Carl . Memories Dreams, Reflections. London: Flamingo, 1989. Menon, A. Sreedhara. A Survey of Kerala History, Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society and National Book Stall, 1967. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Folklore_of_India (web source) Readings in Indian Sociology, Edited by Ishwar Modi. New Delhi: Sage, 2014. (This 10-volume series, is a collection of rare and invaluable essays on Indian sociology published over the years in the Sociological Bulletin, the oldest sociology journal in India, published by the Indian Sociological Society (ISS) Sankunny, Kottarathil, Aitheehya mala (The Garland of Legends) original source in Malayalam. Wiley, Cynthia J., "Collective Memory of the Prehistoric Past and the Archaeological Landscape" (2008). Nebraska Anthropologist. Paper 43. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/43.The author is a poet, independent critic and former Head, Department of English, Pondicherry Central University, India.

Leave a Reply