Foreword

Darius Cooper reviews four Ritwik Ghatak films—Meghey Dhaka Tara, Subarnarekha, Ajantrik and Jukti Tako Ar Gappo his last film for their potrayal of tragedies that evoke foreboding of punishments by forces beyond the control of the protagonists and tears and mourning among us watching them.

We carry the essay in two parts. Below Cooper looks at Meghey Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha–The Beacon

*****

Darius Cooper

W

hy do tears connote shame especially when one insists on talking or writing about them?If films were made to make people laugh films were also made to make them cry; but what makes one cry, the material, has to be moving. But this prompts the question: How is our crying to be brought on; how is it to be facilitated; and how does the text that promotes the crying function to generate the overwhelming effects of tears? In his essay, “Bengali Cinema: Literary Influence” Ritwik Ghatak adds the class debate to this climate of tears undertaking: “Bengali cinema has been a middle class affair…if I may say so, weeping is one of the pleasures of people from the middle class. They like to have a good cry. They seem to derive some kind of pleasure from such crying.” In addition to this, he refers to crying in “The Epic Approach,” as a significant quality of “an epic people…we are not much sold on the ‘what’ of the thing, but the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of it. This is the epic attitude.”

The rhetorical procedure from literary theory might help us in the voyage to Ghataak’s landscape of tears. “Agnition” produces a moving effect at the moment when it is actually shown occurring, and this moment is exclusively constructed in the narrative as deliberately coming “too late,” especially when the character is at death’s door.One needs to extricate all those elements involved in “the belated agnition” and the reactions it brings forth in the audience. This is illuminated in Ghatak’s films through his powerful and moving preparation and presentation of death; Neeta’s tubercular death in ‘Meghey Dhaka Tara’\Seeta’s suicide in ‘Subarnarekha’; Nilakantha’s death-by-alcohol in Jukti Takko ArGappo; and the mechanical demise of Jagaddal, the 1920 Chevrolet cab of Bimal’s, in Ajantrik.

What makes all of these deaths moving and elicits our mourning is the victimizations that are presented by Ghatak in their most radical forms. These deaths occur in an irreversible moment in time. His doomed characters and the car are subjected to a chain of causes far beyond their control, and as we witness them, we cry out of a sheer sense of powerlessness because we are unable to prevent them from dying. There is also an element of guilt that adds salt to our tears because these deaths are enacted as disproportionate punishments and it is this element of disproportion that insists on the continuation of our weeping. What complicates matters are two kinds of punishments that are designed by Ghatak and presented in escalating degrees. The first comes from the calculated cruelty practiced by authority figures around them and the other element which, while not possessing any discernible human character, often takes the form of a fatal sickness brought on by a nagging cold, a neglected cough or the dramatic peripatetic changes of circumstances, all leading toward an abyss from which it is impossible to return.

In Meghey Dhaka Tara we are introduced to Neeta as being born on a Jagaddhatri puja day. This traps her into playing the archetype of the all-caring mother to her lower middle-class refugee family. The abduction of her own mother’s normal maternal function in her daily dealings with the family also helps. Made bitter and cruel by years of poverty and deprivation, this matriarch emerges as a formidable antagonist to her naïve and nurturing daughter demanding from her one sacrifice after another. In the powerful opening scene of the film, we see how Neeta allows herself to be literally ambushed by her family, especially on the day when she receives her tuition’s salary. First she is stopped by the neighborhood grocer who complains that the family is in financial arrears for unpaid groceries consumed over the last two months. Shanker, her jobless hamsadhvani musical brother asks money for a shave and a pinch of the local jarda. Geeta, her attractive and bored younger sister demands a sari. Montu, her youngest brother, must also have his footballer’s spiked boots for the next important match. In the next sequence they all get their demands. Neeta is so much in love with them that she has no money left to repair her own torn slippers. Beyond her selfish family horizon, there is another dependent that preys on her. It is her boyfriend Sanat who she supports so that he can carry on his research in physics without any financial support from any kind of scholarship. She nurtures hopes that he will become, someday, a great scientist in the same way she dreams of her useless and idle elder brother becoming a great singer.

![]()

The pressures on Neeta mount disproportionately as the narrative drives her relentlessly to her own extinction. Her old poorly paid schoolmaster father has an accident and is suddenly incapacitated. Neeta has to give up her studies and take a job. She turns down Sanat’s marriage proposal because her family now is totally dependent on her for their survival. Then Montu has an accident and it is left to Neeta to do all the running about and raise money for hospital expenditures. At this critical junction, her own cruel mother intervenes, encouraging Geeta to seduce Sanat and succeeds in having Sanat marry her voluptuous daughter so that her family’s domestic fires are kept burning via the overwhelming sacrifices offered by her older daughter. In an act of overwhelming cruelty, the old lady demands that Neeta should even give away the money saved for her dowry to Geeta since she will never marry and Neeta shockingly agrees to this “dark” deed. She is too “dark” skinned anyway to accept or encourage any future suitors. The mother’s biting words fall like whiplashes on poor Neeta and are actually magnified by Ghatak as whiplash sounds that erupt on the soundtrack in that shocking scene when Neeta surprises Sanat actually being seduced by Geeta in his own apartment!

All of these processes bring on an exhausted feeling of surrender leading inevitably to her second punishment which is even more excessive–a shattering diagnosis of tuberculosis! Once this happens, Neeta withdraws into a room where she confines herself lest she infect the others. She has deadly bouts of coughing blood that she conceals from all at home and from her peers in her office. It is left to Shankar, her musical brother, to reveal her rapidly deteriorating condition to the rest of his family members on the day of his triumphant return from Bombay as an accomplished musical artist. Only the lunatic father, in the appropriate Yeatsian metaphor of “the rag and bones home of his heart” has realized his daughter’s merciless exploitation and when Ghatak, in a wide-angled moment of monumental ferocity, has him point his finger at all family members and shout “I accuse,” Shankar can only respond, “Who,” and to our accompanying sobbing and that of the others in that family courtyard, we see the lunatic’s pointed Michelangelo finger suddenly break its spine and hang down in conspicuous shame and defeat.

Ghatak builds up our catharsis, not only on the familiar Aristotelian levels of pity and fear, but notably adds a significant amount of anger to the emotional cauldron. The breakdown of all communications between Neeta and her family members has constituted an essential step toward her inevitable final catastrophe. The father, after his accident, has nothing to say anymore. The mother offers more whiplashes. Shankar leaves the house and migrates to Bombay. Geeta overwhelms Sanat sexually and Montu ends up being fed medicinally and hooked up on tubes in the hospital. Nobody has anything left to say to Neeta. Neeta’s paradoxical response also takes the form of silence and when her lungs spill blood, she is forced to take a long holiday from all normal utterances. When a repentant Sanat meets Neeta, after the failed marriage of Geeta, she stoically acknowledges her dharma toward him and her family as “a sin.” “I never protested against any injustice,” she tells him as she walks away from him (and her family) silently into the sunset.

But where does this pride and this silence in her come from? In her silence, we see Neeta slowly becoming aware that she is better than her family, but this realization has to unfortunately remain unspoken. That is why it elicits from us a powerful cathartic response of tears. If she had spoken out, she would have aligned herself to the pettiness of her family and given them a superiority they no longer deserved. In fact, it is her insane father that endorses her silence powerfully when he bursts into her room, one rainy night, and tenderly tells her “to run away” from “this cursed house.” “They, are thinking of adding a new floor to their house” (with Shankar’s newly earned wealth) instead of finding an effective medical cure for her disease.

If Neeta finds herself alone, then Ghatak shows us, how she has to build another hierarchy and take responsibility for it. But when she tries to do that, the results are extremely traumatic. In Freudian terms, her precarious state of ‘civilization’ has to be measured against ‘the discontents’–her family. This imposes sacrifices that in Neeta’s case results in the giving up of all her pleasure principles: abandoning her studies and losing her fiancé and dreams of marriage (along with her dowry and jewelry) to her ungrateful sister. But there is a second sacrifice and this is the giving up of her own super ego interventions. She cannot use her moral principles against her family. As she acknowledges to Sanat: her dharma suddenly stops being a duty and inevitably becomes a sin. She refuses to point fingers at anyone except herself, so her ego is never called upon to address any realist principle by virtue of which she can prevent herself from heading straight for the abyss. Such an action keeps us mourning constantly for her.

But our tears are leading us not only to melancholia but also to anger. And it is this that renders the ultimate homage Ghatak makes us offer his doomed heroine. In her one inevitable outburst of passion, Neeta reveals to Shankar at the sanatorium, where he has placed her, her fatalistic desire to live. “I’d love to live. I’ll live. Tell me Brother, for once, that I’ll live. I want to live–live.” This tension bursts on our nervous system and our eyes have to literally enlarge their orbits to allow the ocean in our tears to finally spill all over. While providing Neeta with a tragic epitaph, our tears are now also made to gather anger for the fatal postmortem scene that follows.

After Neeta’s death, it is the same neighborhood grocer who steps forth and provides Shankar and us first with a choric form of that anger. Shattered as we all are by her death, he recalls her as “a young woman no one remembers any longer (the irony is that she was forgotten even when she lived and surrendered herself to her family’s relentless demands) who would go out in the morning dragging her slippers and come back in the evening: such a quiet girl.” As Shankar looks away (confirming the irony), another young woman comes into view, a woman from the same refugee settlement, who smiles at Shankar and then bends down to discover that like Neeta she too has torn her slippers. But she cannot stop. She has to walk on towards that other family that is waiting to ambush her as well. Our anger renders us impotent at this stage like Shankar who is unable to do anything to prevent this other Neeta from going to her extinction in the same ways his sister did. To wash her with tears is the only alternative Ghatak leaves him and, as the lights in the auditorium come on, us. But those tears will not dry on our faces. The salt in our catharsis will not allow that.

*****

In Ghatak’s Subarnarekha Seeta is another woman trapped in the nurturing mother archetype. She is first seen as a child living in a refugee colony with her very elder brother Ishwar and Abhiram, an outcaste Hindu boy who has been befriended and lives with them after his mother had been abducted by a powerful landlord’s thugs.

![]()

Despite being called “a deserter” by his friend Hariparasad, Ishwar, as the symbolic father to his two little wards, takes up a job in an iron foundry in Chhatimpur on the banks of the river Subarnarekha. He sends Abhiram to a boarding school while Seeta remains at home playing the proverbial role of being both sister and mother to Ishwar. Her only foray into being a pretty woman occurs when she occasionally steps out of her sister/mother archetypes and learns how to sing as a woman yearning for love and marriage with the proper man near the banks of her beloved river.

The proverbial causal chain of death is set in motion with young Abhiram’s return after finishing his school education. As children, the one operatic moment that both had shared occurred on the banks of the river in an abandoned nearby aerodrome. Lost amongst the ruins of that airstrip, this little boy and little girl had plunged with wonder into that forgotten past where planes landed and took off into the skies above. But playing in the midst of these ruins Ghatak presents their innocence to us in a frighteningly ominous way. Those clear skies could be invaded by clouds and this earth could swallow them up. This happens when Seeta is very young and frightened on that airstrip by a monstrously painted, wandering Bohurupee figure and runs out screaming in panic. The stage is set for the darkness that now awaits her. And it arrives when Seetha’s mother and sister archetype clashes violently with her approaching femininity which tragically reveals that in addition to the motherly love she still feels for Ishwar, she also feels a newly awakened woman’s love that very quickly replaces her sister’s love for young Abhiram.

The pressures to break this new bond now starts coming from a patriarchal Ishwar. Determined to interfere and severe this dangerous affection between his two young wards, he plans to send Abhiram to Germany to learn a trade instead of allowing Abhiram to develop his talents as a writer. Wanting to discourage and to end once and for all this menacing romantic alliance of a young writer with the signing talents of his attractive sister, he suddenly arranges her marriage without her consent to a proper high caste Hindu stranger. This provokes the emergence of the fierce mother archetype in Seeta. Determined to punish Ishwar for the sacrifice that he is demanding from her, she elopes with Abhiram on the day of her marriage itself and the two grown up children now run as far away as they can from that abandoned airstrip and that idyllic river and struggle to start a new life in the furnaces of the cruel city of Calcutta.

While we applaud Seeta’s actions because she is bolder than Neeta in not wanting to offer her sacrifice when it is demanded by her brother, we are also fearful for the young couple’s future. The breaking of the umbilical cord is painful because Ghatak offers it as a punishment for all three participants. Our tears, therefore, have to be distributed equally between this trinity and Ghatak’s presentation of this is brilliantly rendered here.

Ishwar’s punishment is enacted in a unique way because he chooses to inflict it on himself. When he suddenly finds himself all alone he is compelled to build a new hierarchy, and take responsibility for it. But when he tries to come to terms on a daily basis with an empty house, a silent river, and the burning fires in his factory’s furnaces, the result is traumatic. So he tries, as his first punishment, to hang himself. He wants to perform it as a moral act of redemption. He feels guilty for having expelled Abhirim and Seeta from the comforts of a loving home to the bowels of a cruel city. But when Haraprasad suddenly interrupts his suicidal attempt because his wife had killed herself and her children precisely in that same super ego way, both men in their joint desperation allow their pleasure principles to reassert themselves by recklessly embarking to that same cruel city that had swallowed up Abhiram and Seeta. They temporarily immerse themselves in all the sins it has to offer to their smouldering and ever-burning ids. Ishwar and Hariprasad’s one-sidedness, the sin of sins, that they had practiced in the refugee colony, is now vehemently replaced by an orgy of reckless drinking in one of the city’s notorious night clubs to the accompaniment of Fellini’s Patricia melody which instigates them to drink even more in order to forget rather than to beg for forgiveness for the devastating extinctions of their families. Regarding reality as their sole enemy now, they first drown it in large quantities of alcohol and while Hariprasad succumbs to a drunken slumber, a violently drunken Ishwar stumbles out of the first inferno of the night club and steps into the proverbial next one–namely a brothel. Not only is reality too strong for him to handle, he wants to replace it, first with the nightclub alcohol version of it and then with the sordidness of the brothel. This kind of a determined excess in Ghatak’s presentation brings forth the first stirrings of the ocean in our tears. But the flood is yet to come. And in order for the dam toburst, we have to first confront the punishments suffered by Seeta and Abhriam with the same city that is punishing Ishwar as well.

Abhiram cannot provide for Seeta and their young son Binu from his writings in Calcutta. So he becomes a bus driver. Seeta has to work very hard at home to put food on the table from the meager salary provided by her husband. One day, tragedy invades their life suddenly and graphically. Abriham’s bus’s brakes fail. Unable to control it, he accidentally kills a young girl. In retaliation, Abhiram is dragged out of his vehicle and beaten to death by an angry mob. This compels Seeta to take up a job as a singer. But that does not pay her bills. The customers want “more” of her, and soon she is compelled to deliver this version of herself as a singing whore in a brothel. On the evening of Ishwar’s carnivalesque quest from nightclub to brothel, she is horrified to confront him, as the evening’s first customer, and terrified by her fate, Seeta kills herself with a kitchen knife before her stupefied drunken brother.

Now transpires the scene when the flood inside our ocean of tears becomes Hokusian. We see a stunned Ishwar staggering drunkenly with the carving blade in his hand streaked with his sister’s spilled blood before all the other witnesses, including Binu, staring at him. As he crumbles to the ground before them having raised the blade upwards to a growl of animal sounds, Ghatak cranes his camera to a great height, and leaving Ishwar in his wild throes below, he brings it straight down on Binu’s face, his eyes staring wildly into the wilderness. It is Binu who will now be forced to bear his inheritance, the burden of this tragedy. Ishwar’s moral speechlessness in this scene is agonizingly made to meet Binu’s moral infantality here. There is sublimity here but the sheer terror of it cannot dry up our tears. Ishwar will spend two years trying to convince the legal law that he is responsible for his sister’s death. While this is true, philosophically and ethically, law works in a completely different climate. Ishwar is proven innocent and Binu, having no other relative, is placed in his custody. In the film’s final scenes, we see Ishwar and Binu embark on their pather panchalis in search of a new life, but how long will it take for their wounds to heal remains an open question. If their forthcoming tears will unite them, their forthcoming anger will also divide them and Ghatak ends the film in this very uneasy phenomenology of resignation.

(To be continued)

___________________________ _______________

Notes

The two quotes of Ghatak above are from:Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema. Calcutta. Seagull Books. 2000. p21 and 25 respectively.

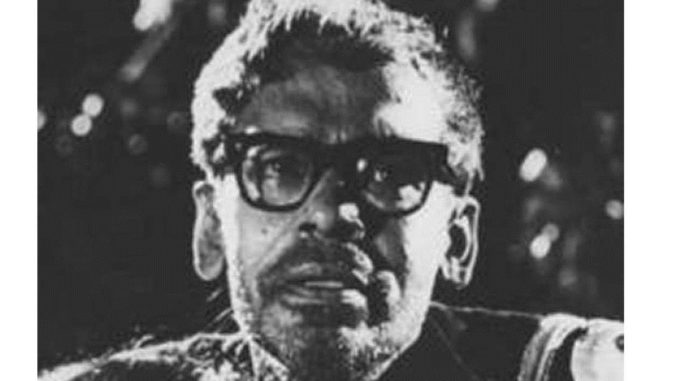

Ghatak Photo courtesy The Hindu.

Also read:

Darius Cooper teaches Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books). Read his review of Kedarnath Singh's poetry 'BETWEEN THUMBPRINTS AND SIGNATURES'. Also, read his essay on Coming Home to Plato's Cave in Personal Notes.

Loved it, I need the full article. I am doing ph.d on Ghataks Mise en scene.