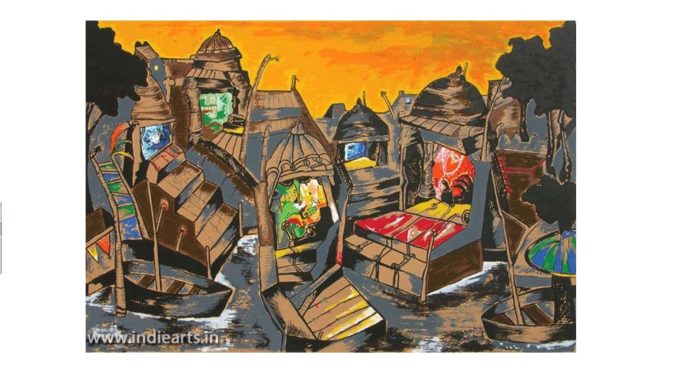

Manu Parekh. “Evening at Banaras.”

Ashwani Kumar

“Born amidst neither fame nor shame, / I came to the world like a dead telegram”. (“My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter”)

I

am a creature of scattered circumstances, odd geographies, and alien languages.I was accidentally born in Gua, my unofficial birthplace in the Saranda forests. Not long ago, the royal family,lecherous priests and brawling miners in this red- ashcolored mining camp-town hunted down dacoits, man-eaters, and mythical shape-shifting snakes to propitiate the river Subarnarekha for digging gold flakes. The tradition of blood sacrifice still continues in the name of flushing out alleged Maoist rebels from the Saranda forests.So far as I remember,my family landed in Gua because of my father’s transferable job in the local police bureaucracy.We travelled frequently from small town to smaller towns and often lived in cheap asbestos hermitages. Forget about Egyptian antiquity or Harrapan myths. We did not even know about the existence of United States of America.Columbus was a lazy donkey in the family barn. If my father smelled anything of his involuntary dislocations, it was his love for hydrogen peroxide and fake Havana cigars.And ‘my mother, mistress of memory’, who never told us that ‘evil demagogue had scarified my father in the blood ritual’, and ‘beneath the underground sky she had stored terracotta of tall men with dry mutton kebabs’, loved worshipping Goddesses of small pox and cholera and dancing at the wedding parties of bhoots and prets especially in times of famine.(“Banaras and the Other”). “Her arbitrary lips, crooked teeth, /old-fashioned illogical dimples, /feverish oxen eyes/ stabbed the drunken hearts of /striplings in the neighborhood / I know for sure/ she never liked blazing May and June. / She was the kind of wife/ my father loved every snow fall’ (From“Have You News of My Mother? forthcoming).

Must confess.I did not speak until I was ten. I only mimicked green parrots and played with pigmy elephants in the Gua forests. I would often stammer, experience paralytic seizures in my throat producing vowels or consonants in any language. Little did my father realize that “stammer is no handicap. It is a mode of speech” and “when a whole people stammer, stammer becomes their mother-tongue.” (From “Stammer” by K. Satchidanandan) My mother knew I ‘was a special child, human or unhuman, and fed pickles of dry Hilsa fish to cure me’ of speech disorder. (‘Banaras…”). Not sure if it worked.

Sounds strange but I was deprived of a mother-language in the conventional sense, for my mother spoke Magahi, a Bihari language. She was neither educated in Hindi nor English, occasionally wrote in now extinct Kaithi script. But she was a great story teller, anecdotal and memoirist. She often relished tales of infidelities in multiple languages including local Mundari. And she made yummy stew of goat’s tongue, liver and entrails.I wonder who taught her to make burrito at night for my father in Gua forests. In contrast, my father was a bit high-brow, fluent with Hindi, and other Bihari languages. He gradually acquired a smattering of English. He was also more stern, formal and ambitious. When not chasing river-pirates, he would read translation of Tolstoy, Lorca and Ibn Battuta. He tried unsuccessfully to publish his ‘motorcycle diary’ in ‘the Red Front and other magazines’. My elder siblings say, he stopped writing after suffering memory loss about his ‘first bribe from a poor widow’, perhaps, ‘Alzheimer comes sheepishly like extra-martial affairs/ Offering instant promise to rejuvenate rotten arteries of lost love’. (“My Grandfather’s…”)

When language came to me, it filled my mouth with half-burnt white charcoal pebbles. I tried the standard Indic language in my mother-tongue. It was sonorous but nauseating. After a psychosomatic test, my grandfather’s friend Dr Nandy advised me to switch over to English. I was told it was the primal language of my ancestors. It was also language of the God. It became an obsession. So when my father scolded me for poor grades in the college, I “ran away with Spanish-Fly-Woman/ I had met at the coaching center/” and learnt English “language skills/from rats, reptiles, insects and part time/teachers with plastic accents. (“Banaras…”). This helped me migrate across horizontal geographies of foreign languages, and live with pre-historic alphabets.After “my sister married a runaway mercenary/from the corrupt ant army/ because he promised/her a free ride from Peshawar to Patna’, my father sent me away to Delhi University for advanced training in Slavic languages so that we don’t get strayed by promises of fake heroes.( “ Banaras…”).

As I entered “my chosen destiny/ I see the face of my old schizophrenic roommate/ His tongue split wide open, hissing over red corns/ And lamenting the loss of his imaginary mango orchards on the Eastern Coast”( “ My Grandfather’s…”). Often, I heard colonial ghosts speak with a chaste Oxbridge accent in the curvy Civil lines trying to convince Ashokan pillars of their loyalty to new imperial jobs.Much to the delight of my friends, every time I began to practice Slavic speech- sounds, I would vomit narrow-eyed Chinese whores in saffron robes, a hilariously sexy scene from the X -files.

After days of repeated practice, slowly, I saw ‘myself multiplying into shirtless, short plump selves; many smelt like lizardsbut some smelt like jasmine buds(“Banaras…”).I can’t say I stopped dreaming about bobsled pursuits for glam Russian blondes, James Bond’s car chases, and prototypes of Stalin. Much as I would have loved to, I failed learning the Hip-Hop songs of purple-skin, mixed -blood slaves from Siberia. So, I ended up joining Aunty Maria’s Zapatista gang on the campus. My class mates say “I loved Pinto beans and red paprika and grew up on pancakes, apple pies, and crunchy crackers in the hostel. After a shot of white rum punch, I would often sing in foreign accent- ‘Picotante, paralysante…picotante, paralysante”. (From “About Aunty Maria”, forthcoming) No wonder, “My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter” with a prolegomenon by Ashis Nandy and “Banaras and the Other” are illegible fragments of self-replicating fantasy language of Goddess Kali in Scottish skirt.

I don’t know how I landed in the twister city Oklahoma in the 1990s, a defining decade in the reinvention of political geographies of India.I trusted James Rennell’s “Bengal Atlas” more than Ptolemy’s mythical world maps. Or maybe something more stupid like I wanted to be reborn as Pinocchio.I vaguely remember I had gone for a ‘job interview at the clinic of Doctor Faustus’ for the position of a language teacher in Delhi.With “private friends/in Salman Khan haircuts/talking of Vedic priests flying in planes,” the bronze-faced Hyena humiliated me in the interview for my crooked hook nose and advised me facial surgery. When I protested, “the giraffe in black hangman trousers tugged my hair in his mouth/ and squeezed my nose so hard, it bled. / All the other external- underwear-superheroes / thumped the table and screamed—” Autopsy done; aliens are evil”. (“Banaras…”)

People say after I returned from the job interview, I had become a ten-inch insect and started crawling. My room mates reported to the Nazis in Khaki-shorts. They came to Jubilee Hall, hand-cuffed me, and banished me to ‘Botany Bay’ on the campus of Oklahoma University in the capital of tornados. I never realised that geographies could be so cruel and alien languages such beautiful punishment. So,I started writing poetry in English with the anger and anguish of frozen butterflies in the claustrophobic tornado shelter on the campus.I must confess; when I heard on the phone in Oklahoma that ‘my mother died yesterday’, my mother -language also died the same moment though I often hear razor-sharp, tongue-lashing, loving voice of my mother. “Like ugly black magic she persuades me to come home/ I see moon dangling from the corners of her cataract eyes. / I see a silent fear planted on her forehead. / I dream of caterpillars singing noisily. /It is time I return home.” (“My Grandfather’s…”). And when I come home, I hear my mother telling me “I don’t want the secret god of your language/ I don’t want anything, anything from you/ I’ll see the end of my language in my language”. (From “A Depressingly Monotonous Landscape” by Hemant Divate).

In short, the more I heard my mother’s voices, I turned more stubborn in my pursuits of odd geographies and alien languages. Strangely, after relocating from Oklahoma, “with long-bearded Darwin/we invented literary traditions under pseudonyms/and smoked Panama cigarettes/in the ruined/monuments of mother tongues” in Mumbai (“Banaras…”) So poets have many heteronyms (proto and para) ala Fernando Pessoa and speak in multiple languages with split tongues. So are Mothers. Mothers, symbolic or real- the primitive, the medieval and the modern (post-modern too)-speak many languages in the fields, offices, markets, parks, underground tubes etc. Mothers- home-makers, single-mothers, heterosexual, lesbians, and queers- are unafraid of speaking up in polygamous languages of love, longing and protest. Singular ‘mother-language’ or ‘father-language’ is a colonial fiction to homogenize the diversity of languages, dialects or accents.

We know languages are rarely analog sampling of images, illusions or metaphors. If you torture languages, they first become ‘stone-pelters’ and ultimately suicide-bombers. No guessing why we ‘see the end of my language in my language’. So, these days I write exclusively in my language- English, fearful of its hegemonic status though. And I speak Hindi at home and mimic incoherently Marathi and Gujarati, my other home languages. I have lost the imaginary capacity of writing in my mother tongue or so-called native language. I used to write letters about love, love and only love to Shinjini, (alias Augusta) in Hindi and especially when we made love with each other ‘in bars, in telephone booths, in running trains.(“My Grandfather’s…”)

Wondering who I am? “I am Urvashi’s daughter and slayer/ of demons in the city of mirrors/ Kunti, Madri, Sachi are my other mothers/ With Dronacharya,/I mastered the art of archery, also the science of conquering hearts./ Defeaters of foes, I also learnt to bare/ my lavish arrow-shaped silver body/ in the divine battle across/Brahma’s expensive canvas../…

“…I don’t want to become Arjuna, again,/ a blind carnivorous beast who/ killed his own cousins, nephews and/ teachers in the age of darkness”.(“Banaras…”)

Poems grow out of fears, fantasies and most intimate memories (sensuous and sacred).My poems come from a ‘hunger’ for my language, like “the fish slithering, turning inside” my mouth. (“Hunger” by Jayanta Mahapatra). If I am an émigré Indian English language poet at Dadar Ladies Bar, it is because “when I reach home, the road I’ve come by begins to weep’. (“Journey” by Jayanta Mahapatra). So “I was wounded early, /and early I learned/ that wounds made me” (Adonis). These wounds are a result of the violence of double selves, the repressed native and the dominant settler playing T-20 in white flannel pyjamas. In other words, there are predictable and unpredictable ways of belonging to self (selves) and languages.So, forgive me if I use artificial sugar in my tea; it is still full of flavor of wild jasmine flowers from my mother’s courtyard in the Olasuni hills. Often, in Mumbai, “we swim upon the memory tea of jasmine, / and somewhere, far off, in the crevices of rogue desires/Bombay Bites and Prawn Pickle Pao/smile, one by one, like good and evil together” (“Banaras…”) Don’t worry. It is a very normal transcultural experience of mutinous dialects and twittering languages. Of late, “I am sick, unattractive, boring /My language is my sex; I am obsessed about it,” (“Banaras…”) Are you still wondering if my English is my language?Or is this simply a case of schizophrenia.Let’s see as I travel to Banaras for committing the sin of beheading imaginary Brahma on the ghats.

“It was the third day of rainbow-lust in the original Vedas. Saturn was in the sixth house”, when I reached Banaras.

“From the medieval mosque to apsidal chaityas/aghoris in twenty-one-yard funeral robes/flogged by lepers, pimps and bootleggers/throng the gates of the Department of/ Religious Tolerance and Piety for free passes/to the shrines of nomadic gods” (“Banaras…”). True, everyone goes to Banaras for “free passes to the shrines of nomadic gods”. But when I visited Banaras I felt as “ If I was still outside my mobile homes in Texas/ Trying desperately to escape from the swirling twister in the cornfields”.(“My Grandfather’s…”) So, in a fit of amnesia, I went to Tagore’s city Calcutta in search of Major James Rennell’s “Bengal Atlas”, and ended up experiencing my schizophrenic struggles with geographies and languages.

I admit that I was not thinking of anything except memories -fictional and real- of Banaras in histories and literature. Elsewhere I have mentioned that while writing the Banaras poem,I felt the lack of a language, of my own. I felt as if I am a lie, fiction and living the truth of another sky. My poem nearly collapsed and disintegrated. I struggled against my past, fading memories of being wounded with syntactical errors and provincial vocabulary.Moreover, writing Banaras was also like inviting trouble. I was very scared. I wrote everyday but also erased the words almost every day. This was insanity. Then I stopped writing. I was able to restart one day after spending time in Kolkata with my elder son Shantanu. He’d left me wandering at the National Library at Alipore. I chanced upon the writings of Major James Rennell in the psychotic – cold basement of the library. The travel memories of first British Surveyor General through lattices of colonial cartography sailed me to a new imagined geography of Banaras. Strangely, I literally dreamed passage upon passage in the poem after this reversal to writing again. I showed the draft to Shinjini. She said, ‘you pray to the rains in Mumbai and praise to a memory ghost’. So, the poem that finally happened was not of my making!

Banaras is a history, mythic and mnemonic and it’s also an imaginary of metaphors.So be not surprised when the famous local bard says , “One half of the city lives in water; the other half is a dead body (shava)”.It resists binaries because it has many selves; it’s primitive and modern. It’s eternal and ephemeral. It’s ascetic and hedonistic simultaneously. It is sublime and so filthy too. Come to Ghats of Banaras. It is a horror and liberating at the same time. It’s so strongly sexual and so deeply spiritual in the same breath as you can’t imagine elsewhere in the world. It exudes such a disruptive, irresistible creative energy with ‘the spoilt blood of ancestors’ it defies the binaries of a conventional moral universe.

Banaras is neither a purely Hindu city nor un-Hindu city. That’s’ why British Surveyor- General James Rennell says in the poem “There was neither government nor religion, nor any ideology. Nothing was proscribed, nothing considered taboo, and civilization existed in simple geographical coordinates…It was not until late evening/that we realized the celestial gossip-/monger’s warning was right./A new republic had dawned on the holy town…” (“Banaras…”) Banaras is venerated by various religions, sects, and practices, sometimes in violent confrontation to the extent that “blood dripping from blood, mostly red” adds new colors to the imaginary Ghats of Banaras. It is actually a sacral, hymnal map without fixed territorial boundaries or geographical coordinates.

There are no border lines between Gods and humans, saints and thugs, wives and whores in Banaras. It is like world-navel mirroring and revealing our deepest joys and fears. This manic beauty of Banaras fascinates me.

Banaras is also a deeply personal experience. In my adolescent days, I used to visit lanes and Ghats of Varanasi while buying Ayurvedic medicines for my arthritic mother. An almost forgotten literary tradition lingers; revisiting it evokes literary and aesthetic experiences. Banaras has fascinated poets like Kabir, Ghalib, Kedarnath Singh, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra and others including Allen Ginsberg and his friends from Beat and the ‘Hungry Generation’. Banaras is always in the memories of a Bengali (literate or illiterate). Tagore’s Ghater Katha still lingers on.

Though Banaras is in the news for electoral insurgencies of “the Great leader, in a golden Afghan jacket, limited-edition watch and Deccan rubber shoes,” and Swachhta campaign, there is a strange silence about Banaras in poetry circuits in English and also other Indian languages.In Mumbai, the term Banaras is almost forgotten literary trope; it evokes the plight of itinerant, migrant laboring masses called “Bhaiyas”; despised and exploited by the city elite and neo- middle classes. So, I also wanted to revisit underground, voiceless subalterns whose smells are missing in boutique Anglophone poetry. Also, there is a dearth of long epic poems these days in Indian English poetry. Recall the long, epic poems “Missing Person” or “Gulestan: A Poem” by Adil Jussawalla or Jayanta Mahapatra’s “Relationship”,the “Jejuri”series of Arun Kolatkar and lately Ranjit Hoskote’s Jonahwhale poems . Lastly, possibly I was attempting something absurd and unwarranted. Who knows?

Incidentally, the publication of “Banaras and the Other” led to the visibility of the “My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter”-‘a box-like machine that might or might not have been an early version of a typewriter’. Published in 2014, ‘My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter’ with a prolegomenon by Ashis Nandy is largely a collection of whimsy montage poems(published and unpublished) I wrote while travelling between Delhi and Oklahoma.On a personal note of disclosure, I have known Ashis-da for more than three decades as an early mentor, friend and a major source of unclaimed ‘political unconscious’ in my poetry.

Noting irreverential imaginary, and a hint of totemic fantasy for schizo analysis in my poetry, Nandy suggested the quirky, playful and imaginative title to this collection.In the prolegomenon, Nandy tells an alluringly delightful story about how he thinks the “poet sleeping peacefully” in Ashwani (or aswini babu) had been awakened by the spectre of a typewriter that once belonged to his grandfather. Apparently, my fictional grandfather had a “writing machine” — a rarity in those days — which he showed Nandy’s grandfather, “a chivalrous pirate” in Bengal. The latter had been so enchanted that one day he snatched it from his Bihari friend in Gua, and simply ran away with it. Unfortunately, every time Nandy’s grandfather tried to show it to others, including his wife, they could not see it!Are you still surprised why major poets in Indian English and Bhasha literature could not notice my poems in the early days of my writing poetry?

In contrast, “Banaras and the Other”, is a political fantasy. And Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh’s classic, long poem Andhere Mein (In the Dark) was the inspiration in the subconscious.In the volume, I speak in the second voice and the third voice, alternating with the ghost first person narrator blurring the fake binaries of linguistic experiences.’The other’ in the anthology is agnostic to social and anthropological categories. It could be anyone facing persecution, oppression, and marginalization at the hands of majority (numerical, material or symbolic). Writing about poems in this collection, K. Satchidanandan reminds me that “the personal and the political, memories and experiences, ribaldry and nostalgia, mythical characters and their contemporary parodies, mix and mingle in diverse proportions…”.

Revolving around part fictional and part factual 1809 Lat Bhairon riots in Banaras, the lead poem “Anatomy of Baranassey as told by Major James Rennell”, the Surveyor-General of Bengal who carried out first comprehensive geographical survey of much of India and also published The “Bengal Atlas” is actually a cartographic poem mapping what Ranjit Hoskote says are the “fissured, schismatic scenarios of 21st-century India.” Compared to “ Imaginary Typewriter”, “Banaras and the Other”is grand in scale and ambition as it interrogatesa virtually worldwide impulse towards genocide and violence against minorities and dissenters, with fear serving as the basis for campaigns of group violence. It is about rising furies of newer forms of fascism, demagogues, false Gods and fake heroes in contemporary India. Recreating haunting images of vernacular- life worlds in English poetry, the poems in the volume also pay rich tributes to great Mumbai poets like Arun Kolatkar and celebrate the open, inclusive spaces like Kala Ghoda in the city of Mumbai.

Make no mistake that our age has become a horrible caricature of itself; more intolerant, narcissistic and an addict of exhibitionism– the new opium of masses.When challenged by dissenters, it becomes a necrophilic experience, too.

Strangely, “My Grandfather’s Imaginary typewriter” and “Banaras and the Other” also share some striking similarities- whimsy, subversive and carnivalesque nature of my “many selves”. In case, you are wondering about why I am planning a trilogy on pilgrimic cities in India I must say few words.You know every holy city contains an unholy city unaware of its own existence. Holy or Religious cities like Banaras or Ayodhya are desire-geographies – border cities between opposing desires of servitude and freedom. And they are also comical, absurd, “theatre of cruelty”. Though they are often found on the last pages of Atlas, such is the seduction of the holy cities that you are powerless in resisting your desires- divine or malignant.So, not surprisingly after Banaras, I am rushing to Ayodhya for the next in the trilogy and re-telling King Ram’s story from a mytho-poetic perspective and rediscovering untold stories of Ram’s shoe fetish, Sita’s wardrobe malfunctioning fears, Laxman’s failed date with demon queen in New York, Hanuman’s food fantasies, Ravan’s secret desires for dancing in female-dresses, and regular stories of modern state surveillance.

Though it’s passive for the time being, Ayodhya shows signs that it can explode any day.if Banaras is a city of death, Ayodhya is the city of BIRTH.The place has always fascinated, and also frightened me. It reminds me of dreamed-of city ‘Dimoria’, a city with aluminum-terracotta towers, bronze statue of all the gods’- Hindus, Muslims, Jains, Buddhists, Parsees, Sikhs, Nagas, and others, and where cockfights in brothels degenerate into bloody brawls over Kublai Khan’s original birthplace.As I have just woken up in the dim, lacquer lights on the ghats of Sarayu river in Ayodhya, I recall “my late-night dream” about the local queen Yusa who travelled to Korea in search of her lover. Some legends say, she married Korean King Suro and lived happily ever after. No wonder.In “Waking Early in Ayodhya”, a poem in ‘My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter’, I touched upon imaginary and unorthodox ways of love making in Ayodhya in the aftermath of demolition of Babri mosque.

Waking early in Ayodhya/I recall my late night dream; Highlighted pink cheeks, pine lips, mascara eyes,/ Long lonely collar bones,/ Honeysuckle breasts, queen size lotus buttocks,/ I remember only broken parts, not the whole body./ I also slowly remember/ Dirty brown Chocolate faced banished king/ Venting his dormant desires/ Seduces the wife of deserted saint for one-night stand/ In the kitchen of his divine consort./He spreads his teflon-coated legs/ Bends his artificial arrow/ She quivers, moans in ecstasy/ They mate all day shamelessly/ And the bricks of the mosque fall; screaming/ With each fatal stroke./… From sixth century BC to unknown AD/ The banished king and his casual lover/Have never made love in early December”.

So!From the Shadows…

![]() It was a dark and stormy December day in 1991. Augusta, George Gordon Byron’s half-sister waited anxiously to meet Ashwani at the railway platform in the dead city of Deheri-on-Sone. Talcum-powdered, teen-aged Augusta wanted to tell her illiterate lanky friend that his fugitive verses carried a distinctive whiff of gun powder. She knew he would not admit that he had acquired writing skills from rats, reptiles and insects. She kept waiting for him until the sputtering of the last coal-engine train disappeared into the evening.

It was a dark and stormy December day in 1991. Augusta, George Gordon Byron’s half-sister waited anxiously to meet Ashwani at the railway platform in the dead city of Deheri-on-Sone. Talcum-powdered, teen-aged Augusta wanted to tell her illiterate lanky friend that his fugitive verses carried a distinctive whiff of gun powder. She knew he would not admit that he had acquired writing skills from rats, reptiles and insects. She kept waiting for him until the sputtering of the last coal-engine train disappeared into the evening.

Years later, Augusta ran away with him and settled in a hill cottage. And Ashwani started writing regularly on his grandfather’s imaginary typewriter.

These days, Augusta proof -reads and edits his invisible partial- paralytic poems and quirky prose. And Ashwani leisurely cooks Bihari Litti- Chokha crooning”Ooh La, Ooh La, Tu Hai Meri Fantasy’!

——————- ——————

Notes. All quotes unless otherwise indicated are from “My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter”( Yeti books; 2014) and “Banaras and the Other” by Ashwani Kumar Poetrywala 2017. © Ashwani Kumar

Leave a Reply