Githa Hariharan

Pages 79-81

T

he room was lined with photographs of shaheeds—martyrs. All of them were lawyers. I looked at the one right across from me: he had a full head of hair and thick dark eyebrows; the look on his face made him seem older than he must have been. The man, in his forties, was Jalil Andrabi, a well-known human rights lawyer. I was told he also believed in independence for Kashmir; he was associated with the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). In 1996, he was arrested by Major Avtar Singh of the 35th Rashtriya Rifles unit of the army; the major was, for some reason, known as Bulbul—the nightingale. Three weeks into abduction by the nightingale, Andrabi’s decomposed body was found floating in the Jhelum River. He had been shot in the head, I was told, and his eyes gouged out. In response to the direction of the high court to arrest Avtar Singh, the Indian government said it did not know where the major was. Besides, the major was no longer employed by the army and he had not committed the ‘offence’ in his ‘official capacity’. The army could hardly be held responsible for his actions. Avtar Singh is reportedly living in California, a free nightingale.

We were at a meeting at the Jammu and Kashmir High Court Bar Association at the Saddar court complex. As in Palestine, there seemed to be an astonishing number of the middle class trained to be lawyers in Kashmir. It’s as if there is a hope against hope that the law will set right the crimes of occupation in one case, militarization in the other.

But it was not hope I picked up in the room when people began to speak.

‘We don’t need your healing touch,’ one man said bluntly. Then I got a taste of the words that would punctuate all accounts: ‘your people’.

The anger and frustration in this room had a specific edge:

these were lawyers, and how must they see themselves if the law itself had gone awry? It is hard to imagine any lawyer applying the word legal to the workings of the Public Safety Act (PSA)—a law that allows ‘administrative’ and ‘preventive’ detention without a specific charge or a trial. The Bar Association’s own president, Mian Abdul Qayoom, and its general secretary, Ghulam Nabi Shaheen, were among those who had been detained. Mian Qayoom was detained for ‘illegal activities’ such as pro-secession protests. Later, the detention order got more elaborate—the charge was sedition and ‘waging war against the state’. Ghulam Nabi Shaheen was detained for similar charges, and for organizing protests against the detention of Mian Qayoom.

This is the point that was being driven home to us: the members of the Bar Association were taking on matters involving the violation of basic rights—cases of ‘enforced disappearances’, for example. And intimidating lawyers, or punishing them with detention on vague charges, or charges of political protest, was a way to keep them in line.

The lawyers said to us, ‘As many as 99.9 per cent detention cases are quashed, but still, anyone can be suspected and detained. With laws like this, anybody can be killed anytime, anywhere.’ Independent reports bore this out: in 2010, for instance, Amnesty International estimated that over two decades, between 8,000 and 20,000 Kashmiris had been detained under the PSA.

More than one lawyer in the room said to us, ‘Please educate the people of India about us.’ This was the education we were to take back, the hard lessons, the unbending syllabus: ‘Our rights are being violated day after day. Our leadership is not allowed to interact with people. They use the excuse that a house is being used for terrorist operations and the house is destroyed. We are losing lives. We have lost nearly a whole generation. If you push us to the wall, what will our boys do?’

There was bitterness whenever democracy came up in the conversation—the word was constantly coupled with Delhi. ‘The high court is disabled, the judiciary is not working, the local press is gagged.’ As for that great romantic image of Indian democracy, the election: no one took seriously elections ‘facilitated’ by men in khaki and green, elections that required a good number of people to be kept out of the way in jail. And those who talk of ‘human rights’ and ‘development’ as if these live in a vacuum—they, we were told, miss the real, political point. Democracy cannot be curfewed democracy. One lawyer summed it up: ‘Democracy and freedom mean choices. What choice do we have?’

********

Pages 81-84

T

he next morning was gloomy. Though it was April, the overcast sky hung heavy with wintry foreboding. We were driving to Kupwara, north of Srinagar and, unfortunately for the people living there, close to the Line of Control between India and Pakistan. Parts of Kupwara are famous for the beautiful meadows and fresh air. It was also in Kupwara, in a township called Machil, that three young men, Muhammad Shaif Lone, Shehzad Ahmed and Riyaz Ahmed, were killed in April 2010. They were supposed to be ‘infiltrators’; terrorists from across the border. It turned out the ‘encounter’ was staged to collect the reward for killing infiltrators. The three young men singled out to play terrorists had been lured with the promise of jobs.

We saw something of the famous Kashmiri hospitality during our day in Kupwara. But always, sorrow lay like a skin over friendly words and gestures. Living for decades in the midst of infiltration from across the border, different brands of militancy and, most of all, counter-operations by the army, had taken all the fabled fresh air out of the place.

The town hall in Kupwara was full. A man got up with the air of making a formal statement. ‘Kashmir is an international issue. It should be resolved with UN resolutions.’ Another man jumped up from the last row of the hall, disrupting the seminar feeling before it took hold of the room. ‘No compromise,’ he said clearly. ‘Yeh mera watan hai, yeh mera mulk hai—we will not go back from our demand for independence.’ His friend, who had been nodding approvingly, added, ‘If you can’t prevail on the powers that be, don’t come here and talk to our civil society.’

There was a pause. As if to soften the angry moment, a man with a beautiful long face and a colourful sweater stood up. ‘We didn’t chase away the Hindus. Jagmohan did. We will welcome them back.’ He smiled, as if ready for that homecoming this instant.

(I had heard, the day before, one brave variation of this painful chapter in Kashmir’s recent history, the exodus of as many as 100,000 Hindus in the years following 1989. Amit Wanchoo, a Kashmiri Pandit trained as a doctor, told us how his family chose to remain in the Valley—even after his activist grandfather was killed by militants. ‘That one decision, not to migrate, and the huge support of my Kashmiri friends, ensured I didn’t get to be anti-Muslim.’)

In the Kupwara town hall, the next speaker was a tall man in a blue jacket. ‘We wish Hindustan well,’ he said, ‘but…’ He spoke softly and reasonably; I could imagine him persuading people though he seemed to have rehearsed what he was going to say. ‘I want to stay with Hindustan. But if Hindustan does not have space for Arundhati Roy, what place do I have? If Hindustan does not have space for Muslims, what place do I have?’

No one picked up the Muslim thread. I couldn’t help being heartened by this, though I knew that the Kashmir I saw had changed in ways not always visible. The old Kashmir, hospitable to a range of ideas and beliefs, a confluence of meeting rivers, had been pushed into the past. The great game of mapping had drawn new borders and boundaries. Along the way, Kashmir’s inclusive Islam had been dented by conservative versions, both imported and home-grown.

Now that the necessary gestures had been made, we got down to business. Some of the people in the town hall had talked to delegations before. But they were not done with what they had to say. There was desperation to be heard; everyone wanted to speak.

‘Four of our children were killed by the army.’ (Cries of Shame! Shame! filled the hall).

‘Sixty women were raped close by.’

‘A woman gave birth to a baby with a broken arm.’

More eyewitness stories followed, the sort that cannot be politely wrapped up in the impersonal phrase ‘human rights violations’.

‘The Government of India and the Government of Jammu and Kashmir have no faith in their own judicial system. They are not governed by rule of law themselves. We live in a very big jail, a jail run with sticks and guns. A danda-raj.’

‘Politics is something we have learnt through suffering. We have nothing left to lose.’

A bespectacled man wearing a beret asked us sharply, ‘What does security forces mean? Does it mean the killing of children?’

It was almost a relief when the sang-lazan, the stone-pelters, got their turn to speak.

The boy stood with his feet planted firmly on the ground. ‘I am Dar Rashid, Stone-Pelter,’ he told us. He described what it is like to be tear-gassed. He spoke of his mother and sister, their sufferings. ‘I can’t even cross the road,’ he said, ‘without being stopped by an army convoy, or being asked who I am. That’s why I throw stones. I am a stone-pelter.’

The next stone-pelter, Muzaffar, was not young or a student; he was a schoolteacher. ‘I lost my job because of an FIR,’ he said. (By now, we had heard of so many First Information Reports with the police that an FIR was like a compulsory entry on a CV.)

Another teacher said he was also a school principal. He added, with some pride, ‘Why does a principal start pelting stones?’ He answered the question himself: ‘I can’t sit with my hands bound.’ He took a deep breath, then burst out, ‘I want my Kashmir free.’

*******

Pages 84-86

F

ree. And like a mirror image that distorts words, pushing us to the wall. Danda-raj. We heard different words that told us this same thing: they were living in a situation, and with the constant feeling, that they had no choices, they were not free. Certainly, the Kashmiris I met did not think they had a share in Indian democracy, such as it is. And after the peak reached by popular protest in 2010, the cry for azaadi was only growing louder, more firm. This cry of ‘azaadi’ that has come to live in Kashmir: the word was spoken with passion, or bitterness, or longing. There were many prisms through which freedom was seen, not, perhaps, unlike the ways in which Indians see their ideas of India. In the roundtables I attended, and the breakfast meetings with leaders of assorted groups, I heard much talk of roadmaps. But it was the prospect of freedom that seemed to hold together all kinds of people, all kinds of ideas about how they wanted Kashmiris to live. If the idea of freedom was fleshed out in many ways, there seemed to be no doubt about what made them not free.

‘The substantive content of azaadi cannot be very easily described, but the absence of freedom is a very visible reality in Kashmir.’12 Perhaps it was easier to pull out evidence of absence than to construct what to put in its place. Absence of freedom: the knock on the door and the armed intruder; closures, curfews, crossfire, rigged elections, burnt houses, ‘enforced disappearances’, torture, unmarked graves, widows and half-widows, the missing and the dead.

Even when shots were not being fired, when the streets were open and people carried out their daily business, the memory of yesterday weighed heavily on them, and the fear of tomorrow took root. Even on a quiet day, the absence of freedom was a desolate peace.

Such desolation had no one cause, and the militants, ‘theirs’ and sometimes ‘ours’, were part of its complicated history. But over the last decade or more, particularly with anger and sorrow congealing in the hearts of people in 2010, it was India—or, more immediately and tangibly, the instruments of India. Whether from lawyers, journalists, schoolteachers, stone-pelting boys, housewives or the hard-nosed leaders of various parties and factions, we heard about the mistrust, fear and anger evoked by the ‘security’ forces. There was the apprehension about the increasing amount of land hired or requisitioned by the armed forces. The government was cagey about figures, but estimates were that there was one soldier for every fifteen or twenty people. In 2010, there were 500,000 armed troops, 300,000 army men, 70,000 Rashtriya Rifle soldiers and 130,000 central police forces for a population of one crore.13 Not surprisingly, a generation of Kashmiris had grown up with soldiers at every street corner, and ‘often even in their living rooms’. The presence of such large numbers of troops—and what they could do and have actually done to ordinary Kashmiris—meant that it was getting harder all the time to separate the call for freedom from the call to demilitarize one of the most militarized places in the world.

********

Pages 86- 87

T

hese soldiers, instruments of militarization. The ordinary Indian soldier, like ordinary soldiers elsewhere, is far from home, in a place and situation he does not understand. He is poor. Whatever personal humane qualities he may bring with him to Kashmir sinks into the only certainty available in his new surroundings— loyalty to the force.

Men who follow orders, use order, have their brotherhood, their uniforms and guns; but they also need laws. Over and over again, we heard about the ‘black laws’—the Enemy Ordinance Act (EOA), the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA)—and not just from the lawyers’ fraternity. The PSA and AFSPA had become part of the language spawned by a military siege. Words like ‘encounter’ and ‘enforced disappearance’ had become as commonplace as hello and goodbye. We heard about the ways in which this language and these ‘draconian’ laws could mark the lives of people at any time.

The PSA, we learnt, can mean prison or house arrest without charge or trial. It may be arbitrary; it may be used only to punish the expression of political views. In other words, PSA helps keep anyone—militant, perceived troublemaker or ordinary citizen— ‘out of circulation’.

The AFSPA, in force in Kashmir (and the north-east), defines a disturbed area. If the governor of the state or the central government considers the area disturbed or dangerous, and thinks the armed forces are needed to maintain civil law and order, the place can be declared a ‘disturbed area’. The special powers the title of the Act refers to: firing ‘to the extent of causing death’ if public order demands it; the use of force against those who assemble in groups of five or more, or carry weapons, or things capable of being weapons; destroying any place which may have weapons, from which armed attacks may be made, or which may be used as a hideout or training camp for armed volunteers, gangs and ‘absconders’; entering and searching any premises without a warrant for people, arms, explosive substances or stolen property; and arresting, again without a warrant, and with any force required, ‘offenders’.

In other words, AFSPA lets the armed forces search, arrest, detain and even shoot any Kashmiri with the claim that they are suppressing an armed insurgency.

So while azaadi was, no doubt, ‘freedom from India’ for many people I met, there were other meanings, all of them urgent.

‘Azaadi is freedom from fear and insecurity, the humiliations and atrocities the armed forces heap on us.’

‘Azaadi is, first, freedom from the fauj, every kind of security force.’

‘They can kill a Kashmiri without being held accountable. In fact, a dog’s life is more precious than a human being in Kashmir right now! Thus the first azaadi would be the restoration of the right to life.’

They were talking of the first freedom, the freedom to live, and to live without fear. Without this first freedom, they would never know when and how they would have to submit to someone who had power over them; or when they would be subject to his violence.

********

Pages 88-90

T

his is the kind of life that requires a dose of black humour to help you cope. Kashmir has a traditional theatrical form called Bhand Pather. The bhands travel from place to place, entertaining people with sharp political satire. Or they used to, until criticizing the Indian state (or the militants) became risky. It became safer to laugh at the autocratic raja who ruled before 1947. One of the risky contemporary scripts: a Kashmiri walking down the road is stopped by an army officer. The officer asks the man in Hindi: ‘Gun kahan rakha hai?’ Where have you kept your gun? Like many Kashmiris, the man has trouble with Hindi. Also, he has an uncle called Gani whom he calls Gun-e-Kak, a popular Kashmiri nickname. So he tells the officer in Kashmiri: ‘Haan, Gun-e-Kak garas manz hai.’ Yes, Gun-e-Kak is at home. Of course the officer thinks he has just heard a confession about a gun hidden in the man’s house and begins to beat him.14

I wonder what satirical gem the bhands would have made out of the day I met, one after the other, separatist leader Syed Ali Geelani and Core Commander General Hasnain of the 15 Corps.

Four of us were driven in a jeep to meet Geelani. Along the way, the jeep swerved off the road, came to a halt. The driver got off, and another man, a passer-by, got in. He drove us to a place with a long wall with blue doors at regular intervals. The soldiers or the police—men with guns at any rate—were waiting to stop us at these doors. We got off the jeep. One of our group, an intrepid journalist nothing seemed to faze, made calls, demanding to know if Geelani was under house arrest, and if he wasn’t, why we couldn’t meet him. While we were hanging around, waiting for the unseen higher-ups to make up their minds, I looked around. It was an ugly little alley the wall made; I tried to imagine what we would see if one of the doors opened. It would be, I thought, a congested neighbourhood, small rooms in small houses, one on top of the other.

The call came through and one door opened. Going through the door was like turning into Alice and going down the rabbit hole. The wall with doors turned out to be a stage prop. Behind it lay a beautiful stretch of green grass leading up to a generous-sized house. Inside, we sat on soft carpets, resisting the temptation to lean against the cushions, because we were drinking tea with the ‘patriarch of separatism’, a very thin and very stern man whose woollen cap and white beard made a long face seem longer.

Geelani, we knew, was pro-Pakistan but, of course, he spoke to us of India, not Pakistan. ‘Your work is in Delhi, in India,’ he told us. Men came and went into the room as Geelani spoke. ‘Work to remove the stereotypes Indians have about Kashmiris. Kashmiris can’t be dubbed terrorists. Their struggle is just and righteous. It’s the Indian forces that have unleashed a war of terror against the Kashmiris…’ As if the word righteous prompted him to shift to holy ground, Geelani raised an admonishing finger and recalled Mohammad’s last sermon for us: the sanctity of life, the sanctity of the pledged word, the necessity for living in conditions of justice and equality.

Directly from Geelani’s house behind the wall, two of us went to meet another Syed, another ‘Kashmir veteran’ though on the ‘other side’—Kashmir’s ‘senior-most serving army general’, Syed Ata Hasnain.

The other side certainly looked different. It was like straying into a memory of what Kashmir was like before trouble came to it, except this was a domesticated memory. Everything seemed pruned, manicured and in order in Badami Bagh, corps headquarters of the Indian army. Even the trees and bushes seemed to know which way to grow, when to bloom flowers or shed leaves. But there was time only for a quick impression before we were ushered into a wooden building that used to be a royal hunting lodge. Heels clicked, salutes were made, and we were left with the general in his room.

The general first came to the Valley in 1997 as a colonel. He was in charge of ‘anti-terror operations’ and ‘development activities’. He now spoke to us, in a quiet reasonable tone, of the need to engage with just about everyone, elders, youth, women, businessmen, clerics, academics, hardliners. His approach, he said, was humane. He spoke of a healing touch for the people, of sensitization for the men in uniform.

All this sounded reassuring. It didn’t take long, once outside the regimented garden of the headquarters, for the comforting bubble to burst.

Later I read the write-up the general sent us. It described the ‘theme’ he had chosen to carry out his most recent mission in Kashmir. ‘The theme I have adopted after much deliberation and in light of my past field experiences in the Valley, is of employing “The Heart as MY Weapon”. We need to understand the Kashmiri psyche with sympathy and with love and caring and the heart is the best medium to reach out to the awaam even as we carry out the operational part of our charter of reducing if not altogether eliminating terrorism in the Valley.’

Another man whose poetry knew how to use the heart as a weapon wrote of his Kashmir: ‘Your history gets in the way of my memory.’ And, wrote Agha Shahid Ali, ‘My memory keeps getting in the way of your history.’15

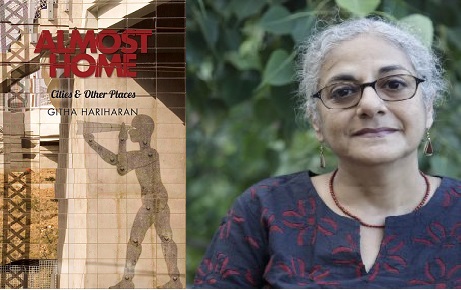

© Githa Hariharan Reproduced with kind permission of the author From Almost Home, Cities and Other Places, Harper Collins, New Delhi, 2014. By Githa Hariharan

Leave a Reply