“Dadi”.

By Mayank Bhatt

“

S

he died last night,” Neeta said; her voice calm, steady, without any emotions.

“Why didn’t you call me then?” I said.

“Bal and I were busy making all the arrangements,” she said. “It was too much work.”

I didn’t – couldn’t – say anything. I’d anticipated this moment – Neeta calling me from India to inform me of Dadi’s passing away – since I’d come to Canada.

I’d always imagined I’d be devastated by the news, that I’d break down, cry. But I was calm. Jane’s presence had changed me, brought stillness, a certainty to my life. It was also the time – it’d been nearly a decade since I had left India. Dadi’s looming presence in my life had faded.

Neeta called when it was morning in Bombay and late evening in Toronto. We’d just had supper and were watching Jane’s favorite crime serial on the TV. She’d muted the TV’s sound while I spoke to my sister. Then, when I told her about my grandmother’s death, she switched off the TV and moved closer to me on the couch. She hugged me lightly and put her head on my shoulder. She smelled of shampoo.

I was lost in thoughts of my grandmother. Tears streamed down. There was so much to remember, but the overbearing memory was her smell – the smell of cooking and prayers. She exuded an odor – a mixture of wheat flour, agarbatti (incense sticks), pooja (prayer) flowers and sandalwood.

Her face was heavily lined with wrinkles and these multiplied a million times when she frowned or smiled. She wore thick glasses that made her small eyes look big. Her widowhood banished colors from her life and she wore only white. She was a widow for four decades and more and now she was dead.

Dadi was a diminutive woman but had a looming presence in our lives. She rarely smiled and didn’t talk much either. She stoically went about doing her chores and lived in our kitchen where she prayed and cooked. The kitchen was small, and it was made smaller by a large storage shelf for groceries. A small mandir was part of the shelf.

Our home was just two rooms – the kitchen and the living room. It smelled of spices and curry, like every Indian home in Canada does. It’s the smell that is released from spices during tampering or tadka as Indians call it. In cold Canada, where homes are ornate cages, and built to retain heat, even a mild tadka sets off the fire alarm, and the smell released permeates everything, and stays on in the clothes forever.

Jane gagged when she smelled it for the first time, her face turned a darker shade of red, and tears welled up in her eyes, even as she tried to smile, and said, “Wow, that’s powerful.” She’d moved into my apartment at Kipling and Dundas West earlier that week. It was the first time I offered to cook Indian cuisine because she claimed she loved Indian food.

Dadi didn’t particularly enjoy cooking. It was more of a chore, a responsibility. She cooked a meal of daal, bhhaat, rotli ne shaak every day. She told me once she’d learned to cook as a child in Olpad, a village near Surat where she grew up and lived till she was old enough to join her husband (my grandfather) whom she had married when she was nine.

Nobody could (or can) cook Aadadh ni daal, bajri no rotlo and lashan ni chutney (served with raw onions) like she did. Dadi also took considerable pains cooking dangerau to get the taste and the texture right. I tried Googling dangerau (pronounced Dang + Geru) but couldn’t find anything remotely similar. Handvo is a close approximation but it doesn’t quite have Dangerau’s roughened texture.

∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞

From the kitchen, Dadi kept a watchful eye on Ma, her daughter-in-law. When she was healthy, Ma had installed a ‘standing kitchen’ in our tenement when it had become a rage in the 1960s, but Dadi preferred to cook sitting on the floor. It helped her cook and pray together, and divide her attention equally between the two tasks. For her, both cooking and praying were chores. She wasn’t the god-fearing type, but life had made her wary of sudden misfortunes, especially after her son, Baba, died. Since then, Dadi performed the pooja every day.

Every morning, after nursing mother and packing lunch boxes for Neeta and me, Dadi had a leisurely bath and then gather her gods – framed photos and miniature idols – and set them up on a flat patlo (a wooden stand), sit on a chatai (straw mat) for her prayers, which comprised a combination of chanting of Sanskrit shlokas, cleansing the idols with a sprinkling of water, applying tilak (head mark) made from a paste of kumkum (vermillion) and chandan (sandalwood).

For each of the idol and the photo, she had a separate shloka. The hour-long pooja ended in a grand aarti which she performed holding a lit diya in the right hand and a small bell in the left. She performed this ritual every day.

In the afternoon she slept and when she couldn’t, she wrote “Sri Ram” endlessly to fill up small notebooks which she dutifully handed over to the priest at the Laxminarayan Mandir to be despatched to Haridwar and immersed into the holy Ganga.

Ma had acute rheumatoid arthritis, which confined her to a bed. In later years, she also developed Alzheimer’s, and Dadi was forced to move her to a sanitarium in Khandala. Dadi had spoken to our neighbors who knew a trustee at the sanitarium. “It wouldn’t cost us much,” Dadi muttered when I said that it’d probably be better if we just kept Ma with us. “Keeping her here will be more expensive,” she said in a tone that discouraged any discussion on the subject.

I remember the day the ambulance arrived in front of our building. Dadi told Neeta and I to hug Ma, which we did, but she didn’t hug us back. She smelled of urine. And her eyes seemed lifeless. She didn’t protest as she was carried out of the house by a burly attendant from the sanitarium. “Be gentle with her,” Dadi said sternly to him.

∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞

“How old were you then?” Jane asked when I first told her about my Ma.

“Maybe ten or eleven and Neeta was seven.”

“And you remember it all so vividly,” she said.

“I remember everything about Ma and Dadi in the smallest of details. Dadi was the most important person in my life – my only parent. Baba died when I was young, and Ma went out of her mind. It was Dadi who raised us,” I said, surprised to hear my voice turning into a hoarse whisper.

“Do you hold her responsible for what happened to your mom?” Jane asked.

“No, I don’t.”

“I think you do.”

I’d never thought about that ever before, but I did remember everything, even the smallest detail. I’d never spoken about it to anyone except perhaps to Neeta, and that, too, only to calm her when she’d angrily accuse Dadi of depriving us of our mother’s presence and love.

Throughout her teen years, and even later, Neeta held Dadi responsible for our mother’s illness. I’ve always felt that when she eloped with Bal, it was not so much out of love for him as it was to rebel against Dadi.

“You’ve had this strange sort of relationship with your grandmother,” Jane said. “Both of you protected each other.”

Jane was right. A million memories were crowding my mind that evening as I thought of her. But two remain etched in my mind. Many years ago, she learned that one of her cousins died in an accident. I took her to meet the family. The auto rickshaw broke down and we had to walk a long way. The walk turned out to be an ordeal.

“Dadi, you’ve come here to console the family so you won’t talk about your trudge,” I told her.

She was too tired to say anything. We sat with the family for a while, and then returned home. Her daughter (my aunt) came visiting us a few days later, and I overheard their conversation.

“He thinks about others. Dukhi thava no chey (He’ll suffer).”

It’s perhaps the best compliment I’ve ever got.

The other memory is when I saw her sitting by the window watching the traffic go by and also keeping a watchful eye on Ma.

“You’re lonely,” I said.

“Ekla rehvani tev chey, (I’m used to living alone),” she said.

That sentence has stayed with me. It’s probably the one thing that we’re not ever prepared to get used to, and inevitably that’s what we have to learn the hard way – to be alone.

∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞ ∞

I called Neeta a few days later. She told me Dadi was worried for me since I’d moved to Canada. “When I think of her,” Neeta said, “I know how similar we both are to her. She never consciously taught us anything. I guess, we just absorbed everything that we saw in her.”

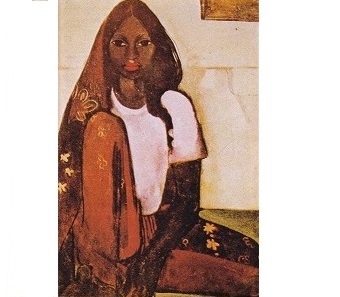

Notes: © Mayank Bhatt Visual: Amrita Sher Gill. The Child Bride 1936. Courtesy WikiArt More by Mayank Bhatt: Married to a Believer Arthur in the rains

Mayank Bhatt is a Toronto-based author. His debut novel, Belief was published in 2016. View Bhatt's blog: www.generallyaboutbooks.com here.

An interesting and descriptive narrative about a grandmother of another culture (from my own). I love reading about other cultures to learn more and to get the feel of the real people. Also, although this piece sounded completely authentic, I wondered if this was a work of fiction.