Riffat Hassan

T

o write a composite account of my experiences in interreligious dialogue is a most challenging exercise, for these experiences, covering more than thirty-five years, have been so multi-faceted and multi-layered that it is impossible to describe them either simply or comprehensively. But, I feel compelled to respond to this challenge because these experiences that are too many, too varied, too deep to be articulated in this essay, have been life-transforming for me, and this is something I feel called upon to share. The fact that I am a Muslim woman—perhaps the only one for a long time in a male-dominated enterprise—intensifies my need to do so. I was thirty-four when I entered a world that was in the process of being created, and today, at age seventy, I am no longer what I was then.

A critical question that has arisen in my mind since I received the invitation to reflect on my experiences in interreligious dialogue is from what perspective I should write this account. Should it be a record of my experiences in some sort of chronological order, from the earliest to the present time? Should it be a statement of how I view these experiences from where I am today? History is unavoidable in the narration of events—whether internal or external—that constitute one’s evolution as a thinking, feeling person. So, in this account there will be a recollection of some of the most significant moments I lived through in my long journey through the maze of interreligious dialogue, but there will also be reflections that are not bound to any specific event but come from a deeper place in me as I am today.

Many things happened in the 1970’s that impacted both the world and my life. In 1972, I migrated to the United States, known as the land of opportunity. Undoubtedly, living and working in the U.S. brought me opportunities I would never have had if I had remained in Pakistan, the land of my birth, or in England, where I received my higher education, but it also brought many challenges. One of these was the negative perception of “Arabs” (who were identified with Islam, even though many of them were Christians) following the Arab-Israeli War and the Arab Oil Embargo (1973), which ushered in the era of “oil politics.”

However, a challenge that had a much deeper impact on me personally confronted me in the Fall of 1974, when I was teaching at Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, and became faculty adviser to the Muslim Students’ Association (MSA)chapter at that university. This “honor” was conferred upon me solely by virtue of the fact that each student association was required to have a faculty adviser, and I happened to be the only Muslim faculty member on campus that year. The MSA had a tradition of having an annual seminar at which the faculty adviser introduced the seminar’s theme. However, in my case, I was assigned a specific subject, namely, “Women in Islam,” presumably because the MSA office-bearers did not think that a Muslim woman, even one who taught Islamic Studies, could have the competence to speak on any other subject. Given the patriarchal mindset of this all-Arab male association, which did not permit women even in the audience, I was not surprised by this. I accepted the invitation mainly because I wanted to present a woman’s viewpoint on a subject on which an endless number of books, booklets, brochures, and articles had been written by Muslim men. In preparation for my presentation

I decided to do a focused study of the qu’ranic texts pertaining to women.

I do not know exactly at what time my “academic” study of women in Islam became a passionate quest for truth and justice on behalf of Muslim women—perhaps it was when I realized the impact on my own life of the so-called Islamic ideas and attitudes regarding women.

What began as a scholarly exercise became simultaneously an Odyssean venture in self-understanding, driven by an intense, existential need to make sense of my own life as a Muslim woman.

But, “enlightenment” does not always lead to “endless bliss.” The more I saw the justice and compassion of God reflected in the quranic teachings regarding women, the more anguished and angry I became, seeing the injustice and inhumanity to which Muslim women, in general, are subjected in actual life. The journey that began so strangely and unexpectedly in 1974—which led to my pioneering work in feminist theology in Islam, and later, to my becoming a women’s rights activist—played a pivotal part in the next major development in my life a few years later.

The immediate context of this development was the Islamic Revolution of Iran, which overthrew Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran, staunch ally of the U.S. in February, 1979. The popular revolution that brought into power Ayatollah Khomeini (who identified the U.S. as “the great Satan”) brought the centuries-old antagonism between “the Christian West” and “the world of Islam” into the open. The long-drawn-out hostage crisis exacerbated the tension felt by many Americans at what was miscalled “the return of Islam.” All of a sudden there seemed to be an overwhelming interest in understanding Muslims/Arabs/Iranians who had become avisible threat to what many Americans felt was “the American way of life.”

Up until that time it had been customary for Westerners, in general, to see Islam through non-Muslim eyes, and there was, of course, no dearth of materials about Islam, the Prophet of Islam, and Muslim peoples by “Orientalists” (to use Edward Said’s term), many of whom had been Christian missionaries who regarded Islam as an adversary religion. However, in the U.S. a select group of persons who were aware that 2,000 years of Antisemitism had contributed to the Holocaust in which 6,000,000 Jews—perceived like the Muslims as the “Other” and the “Adversaiy”—had been exterminated in the “Christian West” began to see the necessity of understanding Islam/Muslims by means of engaging in dialogue with Muslims themselves,

This led to a search to find “dialogue-oriented” Muslims who could explain the meaning of “Islamic Revival” (which in the 1980’s would be called “Islamic Fundamentalism”) to Americans. Since I was a Muslim teaching Islam, I was called upon, with increasing frequency, as time and crises went on, to talk aboutIslam/Muslims in the context of contemporary issues.

I had, of course, been aware of the ferment in the Muslim world and could identify many of its causes. But, coming from a Muslim society in which it was virtually unthinkable that women could speak with authority on any Islamic subject, including women-related issues, I felt ill-prepared to assume—almost overnight—the role of being one of Islam’s “spokespersons.”

On the contrary, having rebelled against the traditions of my Saiyyid Muslim family in the patriarchy-dominated culture of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan since I was twelve years old, it seemed to me to be both odd and ironic that I should be asked to represent Islam/Muslims in gatherings of American Christians and Jews.

However, when I look back at that time now, I see things differently. While I had been protesting passionately since childhood against what I perceived to b gross injustices and inequities in the culture in which I grew up, my faith in God was the rock that sustained me. When asked to define what a Muslim was many years later, I had said, “A Muslim is a person who strives to live in accordance with

the will and pleasure of God.” I know today how exceedingly difficult it is to live up to that definition, for to be a Muslim one has constantly to face the challenge, first of knowing what God wills or desires not only for humanity in general but also for oneself in particular, and then of doing what one believes to be God’s will and pleasure each moment of one’s life. For me the challenge has been ongoing and relentless, making my life a journey from struggle to struggle to struggle. However, in and through all these struggles there is one thing of which I have always been certain: that God has a purpose for each of our lives and that we must remain faithful to this purpose.

Looking back then it does not seem so strange that I felt called upon to respond to the escalating public interest in understanding Islam/Muslims. While I was still learning how to do this in public arenas, I was invited—in March, 1979—by Dr. Leonard Swidler, Professor of Religion at Temple University, to take part in a “trialogue” of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars. Swidler was one of the initiators of this unique project sponsored by Mr. Sargent Shriver, who headed the Kennedy Institute of Ethics in Washington DC. The initiators of the Trialogue considered it important to enlarge Christian-Jewish dialogue to include Muslims, since Islam was among the three “Abrahamic” faiths along with Judaism and Christianity, and also in view of the increasing importance of Muslims in the contemporary world situation. Shriver, an idealistic politician who had been the driving force behind the creation of the Peace Corps, hoped that the Jews, Christians, and Muslims who constituted the Trialogue would become instruments of peace-making in the Middle East.

The Trialogue was a group of about twenty Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars who met periodically for two or three days in Washington, DC, and engaged in a conversation, both deep and wide, which played a foundational role in the development of a new discipline, namely, interreligious dialogue among the three Abrahamic faiths.

I participated in the Trialogue from 1979 to 1982 and can say, with total honesty, that this experience had a transformative impact on my life. When I had first entered this group I had been a highly reactive and fragmented human being, but the affirmation that I received in what became my community of faith enabled me to become much more proactive and integrated. My experience in the Trialogue became the basis of my lifelong commitment to inter-religious dialogue, but it was also associated with some bitter and painful lessons.

It was very disappointing for me to find out, for instance, that, though well-intentioned, a number of Jews and Christians in the group knew very little about Islam, and they tended, therefore, to think of it in simplistic or reductionist terms.

When I became a part of the Trialogue, I believed that, though we came from different religious traditions, we were not going to be limited to, or by, them but were going to step forward and together create a brave new world that would reflect the universality, compassion, and justice of our One Creator.

My idealism was badly shaken when I saw that in times of political crisis I found myself standing alone, as my friends had retreated to their respective corners. In 1982 before I left for a two-year stay in Pakistan to work on my research projects, I felt heart-broken. I felt as if my unquestioning trust about being a part of a community of faith that was going to usher in a new era of love and light had been brutally betrayed.

I did not think that I could ever participate in another interreligious dialogue.

However, the good that I had known during the time I had been in the Trialogue and the relationships I had formed outlasted the disillusionment. I realized that I could not walk away from a life-commitment no matter how many skieshad fallen. In 1984, Dr. Hans Kung, Professor of Ecumenical Theology at the University of Tubingen, with whom I had been in dialogue for some years, visited Pakistan and asked me to arrange his meetings with various groups of Muslims and Christians. I organized these meetings and participated in them.

Following that visit, my dialogue partners in Pakistan and I founded the Pakistan Association for Inter-Religious Dialogue in Lahore. This Association served as a meeting ground for significant interchange between Muslims and Christians for many years.

Looking back over the years, I recall with gratitude the life-affirming, enriching experiences I had as the sole Muslim member of a Jewish and Christian women’s interreligious dialogue group called “Women of Faith in the Eighties.” Participation in several hundred dialogue meetings in many counties of the world has been an ongoing, learning experience that helped me greatly in developing and directing two major Peace-Building programs sponsored by the U.S. Department of State in the aftermath of September 11, 2001 (2002-09). These programs consisted of eight exchange visits by South Asian Muslims to the U.S. and return visits by Americans. The participants were religious scholars, teachers, clergy, and community activists, including a number of my long-time dialogue partners.

Due to our collective experience and expertise in interreligious dialogue, we developed a sustainable network of peace-builders in the most volatile region in the world, as well as in the U.S. It was gratifying for us to know that the State Department designated these programs as “models of all future exchanges involving Muslims.”

A primary task assigned to the “veteran” writers of essays for this special issue of JE.S. is to reflect on the changes in interreligious dialogue during the period of their involvement. With the expansion of Islamic Studies as an academic discipline now being taught at many more colleges and universities than was the case four decades ago, the ever-increasing volume of literature on Islam/Muslims by post-Orientalist writers, and the internet revolution, there appears to be little excuse for Americans to remain ignorant about Islam/Muslims.

But, looking at the Islamophobia that is pervasive in the U.S. today— in everything ranging from immensely popular proclamations of television evangelists to all kinds of writings from scholarly to pseudo-scholarly, to journalistic, to tabloid—I am reminded of T. S. Eliot‘s immortal lines:

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

The cycles of Heaven in twenty centuries

Bring us farther from GOD and nearer to the Dust. (from The Rock, 1934)

During earlier years when I was one of the very few Muslims extensively involved in interreligious dialogue with Christians and Jews, I became aware of some chronic issues that I encountered virtually everywhere.

One of them was the marginalization of women and their issues in the world of ecumenical dialogue. It took me a significant amount of time and effort to persuade my very liberal and liberated dialogue partners in the Trialogue to devote a part of our periodic meetings to discussion on women in the three traditions.

Swidler’s famous “Dialogue Decalogue” had taught us that it was a precondition of interreligious dialogue that each partner define him/herself and that it was necessary that each partner should have a sense of parity or equality with the others.

It was acutely disappointing for me to discover how often the above-mentioned “commandments” were blatantly overridden in interreligious dialogues. It was customary for Muslims to be defined by “others,” including anti-Muslim writers from Bernard Lewis (“the rage of Muslims”) to Samuel Huntington (“the clash of civilizations”) whose views had a formative influence on U.S. public policy.

I also found out that the language of interreligious dialogue was dominated by concepts and categories alien to Muslims. Millions of viewers saw Larry King talk about the “Muslim Bible,” and I have often been asked about my concept of “salvation”—a concept that does not exist in Islam.

Another word commonly associated with Islam—”fundamentalism”— belongs not to the history of Islam but as a subspecies of Christian Protestant evangelicalism, which originated in the U.S. in 1920.

I want to state here that many Muslims, including myself, have experienced cultural colonization and have internalized the vocabulary of our erstwhile colonizers.

With all my reservations, I continued to use the word “fundamentalism” with reference to Islam/Muslims until 1990, when I was invited to write a scholarly paper on “Islamic fundamentalism.” I realized then that authentic answers cannot be given to inauthentic questions, and from that time onward I did not use this term in my writing or speaking.

However, the option of simply not using a particular term does not exist for me in the context of the word that has been misused the most in recent times—”Jihad”—a core quranic concept that refers to the struggle for purification of self and society, not to war.

The world has changed much between 1979 and 2014, but I do not see substantive changes in underlying Western ideas and attitudes toward Muslims. One major reason why Muslim participants in interreligious dialogue with their Abrahamic cousins felt like poor relations was that these meetings—mostly held in the U.S. or Europe—were almost always funded by Jews and Christians.

Now, the landscape has changed significantly, with the establishment of three interfaith organizations by Muslims from ruling families: The Royal Institute for Interfaith Studies by Prince Hassan bin Talal in Jordan (1994); Doha International Center for

Interfaith Dialogue by Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Emir of Qatar; and King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID) by King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia (2011).

In November, 2013, I had the opportunity to participate in KAICIID’s Global Forum in Vienna. At this event, lavish hospitality was offered by the Saudi government to about 1,000 guests (including Swidler and some of my other dialogue partners), representing the five major religions of the world. The theme of the conference was “The Image of the Other,” and an oft-reiterated slogan was “The Other Is My Brother” (no mention, of course, of “My Sister”).

KAICIID’s stated goal is to bring together three significant groups—political leaders, religious leaders, and “experts” (many of whom appear to be either academics or members of interfaith organizations)—using interreligious dialogue as a means of conflict-resolution and peace-building in

today’s divided world. KAICIID has high ambitions and wants to set up its offices all over the world. It is too early to predict the outcome of this grand project, but one thing is clear—with the emergence of KAICIID and a huge influx of Muslim money, a new era has dawned in the world of interreligious dialogue.

In his book An Historian’s Approach to Religion, Arnold Toynbee pointed out that all three religions of revelation that sprang from a common root—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—have a tendency not only toward exclusivism and intolerance but also toward ascribing to themselves an ultimate validity. In my long engagement with Jews, Christians, and Muslims, I have come across this tendency more often than I would like to recall.

I have seen many instances when Jewish-Christian-Muslim interreligious dialogue has degenerated into petty competition, political manipulation, or vain triumphalism.

However, I would like to end this essay by sharing the most precious memory I have from all my years in dialogue. The year was 1988; the place, St. Augustin in Germany. The sponsor of the large Jewish-Christian-Muslim dialogue meeting was the International Conference of Christians and Jews. The afternoon session that day was on the theme of Revelation, and the speaker was Dr. Shah Gamal Solaiman,an Egyptian, Al-Azhar-mined scholar who had been Imam at the Regent Street Mosque in London for two decades.

Shaikh Solaiman was explaining the Islamic concept of Revelation, pointing out that Muslims held the Qur’an to be God’s Word and regarded it with utmost reverence. As soon as he finished speaking, an Israeli rabbi raised his hand. When the Moderator asked him to speak, he said in a very mocking tone qf voice, “As a Jew I see the Bible as a book of fairy-tales. Why do you Muslims take the Qur’an so seriously?” He ended his remark with a smirk and a gesture of exasperation. I remember the pin-drop silence that followed this statement.

The Moderator, a wise man, sensed the tension and declared a “Tea Break” for fifteen minutes. During that time Shaikh Solaiman sat very still in his seat, his face flushed. When the meeting resumed, Shaikh Solaiman started to speak. He said that he wanted to apologize to the group, because when he had heard the rabbi’s words he had felt very angry. But, as he sat in silence afterwards, he said that he remembered that the Qur’an had instructed him to always speak with Jews and Christians “in the most kindly manner.” He, therefore, found it necessary to apologize for the anger in his heart.

As I heard Shaikh Solaiman’s words, I was moved to tears–overwhelmed by his faith and simplicity—feeling utterly grateful for having seen an act of grace that would warm my spirit until the end of my days.

My concluding prayer is that Muslims who enter the tough terrain of interreligious dialogue might be imbued with the wisdom, gentleness, and humility of Shaikh Solaiman, who demonstrated to all of us that day in Germany what it meant to be a faith-filled Muslim who conducted his dialogue with Jews and Christians, as he did everything else in his life, according to what he had learned from the Qur’an.

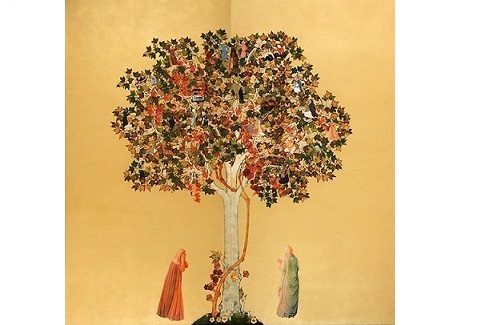

Courtesy: Journal of Ecumenical Studies Volume 19 Number 1 Winter 2014 pp 134-139. Original title: Engaging in Inter-religious Dialogue: Recollections and Reflections of a Muslim Woman --Some emphases in italics added and stylistic changes made for this version. --Visual: Gulam Mohammed Sheikh. Speaking Tree from Kaavad Home. 2005. Courtesy: Vadehra Art Gallery, New DelhiRiffat Hassan is a Pakistani-American theologian and feminist scholar of the Qu’ran and an activist with a focus on Islamic feminist theology and interfaith dialogues. She has taught at Oklahoma State University and Harvard University. She is currently Professor of Religious Studies at University of Louisville, Kentucky, USA

Leave a Reply