Priya Sarukkai Chabria

E

ach of us has multiple Ramayanas circulating in our imagination. Some are befriended in childhood, others come to us through the arts, few through political associations and yet others we create. The epic’s poetry, layered ambiguity, seam of changing love and its companion loneliness, savagery and its idea of “a consciousness hidden from itself, or, one might say, of an identity obscured, and only occasionally, in brilliant and poignant flashes, revealed to the owner“1 makes this a story one comes back to time and again.

My introduction to the Ramayana was aural, in my grandmother’s telling. I was about four years, and each day over lunch she told me a small part; Patti had a fantastic talent for serializing and unfailingly stopped at tantalising moments: Rama, Sita and Lakshmana seeing the frothing river they had to cross or Ravana dragging Sita into Pushpaka. Of course my Patti spun out the parts with the animals: leaping monkeys and growling bears, Jatayu bleeding, the small striped squirrels… Each animal was kind and helpful however wee; each was performing a sacred duty- as I should, throughout my life. Patti made me understand that the Ramayana was a divine tale and a comforting one; it comforted me enough to not miss my mother with her huge stomach.

After my sister was born, Amma too got into telling me the Ramayana, only now I was Hanuman, tossing cauliflower trees into my mouth, leaping on a snow mountain of dehi-rice that must be eaten to be crossed. I became god’s little helper and the story — a game. I would battle carrot arrows one day, demolish aubergine fortresses the next. I became plump on the Ramayana’s supple tastiness.

Possibly composed in 1CE, the Valmiki Ramayana is hard to match in poetic imagination and beauty. The excerpts2below describe Hanuman as he crosses to Lanka. It compares Hanuman’s size and brilliance to sun, moon and comet, yet tints these with the glow of fireflies and flowers, thus sublimely suggesting his feats during the crossing: he becomes gigantic; he shrinks at will.

That Hanuma who was equal to a cloud, covered with flowers of various kinds, shoots and buds, shone like a mountain with fireflies…

Hanuma shone like a cloud in the sky decorated by lightning, with flowers of various hues sticking to his body…

The round, wide, reddish brown eyes of Hanuma, the best among the monkeys, shone like fully risen sun and moon…

The great intellectual Hanuma, with his great body, and with white teeth, shone like the Sun, being surrounded by his circular tail…

The best among monkeys Hanuma flying thus in the sky, looked like a meteor darting away with great speed in the sky from northern direction…

During my adolescence I read the Ramayana in paperback and comic books, comparing these as I did my career options: should I go for astrophysics and seek stars or opt for the arts? At this stage all versions proved unhelpful, even distasteful: everything was worked out; codes of conduct were laid out, killing Valli whose back was turned wasdharmic, Rama was righteous even when he inflicted suffering on Sita, a woman. In my blood thrummed rebellion. I cast the text aside and turned to disco dancing.

Many years passed. My encounters with the wonderful epic since have primarily come as and through art. Multiple Ramayanas contrasted, enhanced each other, speckled me. From this inner shifting kaleidoscope I choose a few to write about. In almost all instances I comment on interpretations of the various translations.

Cinema first, perhaps, in the form of Arivandan’s mystical and beauteous film Kanchana Seeta/ Golden Seeta (1977). Rama and Lakshmana wander through the forest, seeking Seeta for they need her presence or golden image to complete the ashwamedha sacrifice and control a kingdom. But Seeta is nowhere to be seen. But wait, listen, look: what is the rustling the boughs but her, and the gleam on the river’s body? They are blind to her immanence. Earth goddess, shimmer, the present: all this Seeta is, but they don’t recognise her. Nor do we recognise the familiar Ramayana in this redemptive narrative, but then again we often don’t seem to recognize ourselves in the numinous.

This film makes me remember not the battle-hardened king, but the young Rama inconsolable, grieving his separation from the abducted Sita. Arshia Sattar’s3 poetic translation, steeped in pathos, of the Valmiki Ramayana Valmiki has been my companion for years.

“…The sky, struck with lightning’s golden whip, cries out in pain in the rumble of thunder. And the lightning flashing across the dark clouds makes me think of Sita writhing in Ravana’s dark arms!

Look at the flowers on the hillside, Laksmana! They rejoice in the fresh rainwater and make me think of love, even though I am so depressed…

… I have lost my wife and kingdom, Laksmana, and I suffer like the banks of a river which are slowly being eroded. My grief is boundless, the rains seem endless and Ravana is a deadly enemy. How will I ever overcome this, Laksmana?”

12th century Tamil poet Kambar, author of the Ramayanam Ramavatharam popularly known as Kambaramayanam, weds female desire and devotion to the power of male beauty in luminous verses that describe the effect Rama has on Mithila’s maidens as he strolls down the street to Janaka’s palace. This is my translation of the song Maninam.

Some maidens

sprang like does towards him

advanced with the peacock’s shimmering hesitancy

stood like sparkling stars stunned by His radiance

ran between them like forked lightning

with anklets resounding, bees humming in flower twined hair raced

uncontrollable, uncontainable with riveted gaze

Mesmerizing was the beauty of the Eternal One

Those

who saw his shoulders were transfixed by his shoulders

who saw his feet were transfixed by his lotus feet wreathed in sturdy anklets who saw his long arms found their gaze captured here.

Spellbound maidens flashing sword-like eyes saw

in each part His entire enthralling form

I fell in love with Ravana after seeing Margi Madhu in a Koodiyattam performance as the demon king; he was a king of loss. The selection from the Aranya Kanda of Valmiki’s Ramayana4 presents Ravana’s attraction, savagery and tragedy. “Similar to the Sun in the firmament, seated on a superb golden throne resembling a golden Fire-Altar, Ravana himself seemed like the ritual fire which leaps when the altar is drenched with ghee … (He is) One who is severely wounded in countless combats by thunderbolts from Indra’s Vajra, whose chest bears the gore marks of lordly Airavata’s tusks… The verses also term Ravana, “envious demon“, who habitually chased sages’ wives and was given to drink and destruction. Paula Richman mentions the shadow puppet theatre of Nagarkoil in which Ravana, distraught father and all too human, laments as he bathes the body of his grown son slain in battle5:

At night I used to hold you in my lap and feed you soft rice until the moon rose; then I pointed to it and sang, ‘Come down, little moon, come down and play with my little boy.’ And you, when you saw the rabbit on the moon, you jumped up and down, trying to catch it.

And in these verses (in my translation6) Mandodari weeps for her husband:

“Ah my king!

Your face, once so tender and lustrous

as moon, lotus and sun, flashing gems

your wild eyes which rolled in revelry

your heart-stealing smiles

lord whose talk delighted me – today

you lie dyed in tangles of blood, marrow shattered

and soiled by the dust of passing chariots.”“King!

Your body glossy as sapphire, gigantic

as a cloud capped mountain, swaying with necklaces

of cat’s eye, pearls, garlands like streams, jewelled

as a thunder cloud radiating lightning – lies still

today, tendons hacked, oozing, your organs impaled

by Rama’s arrows like spines of a porcupine!

How can I hug you…”

Margi Madhu’s Ravana was this magnificent beast and aesthete, all craving and threat, tears and screams, ricocheting between despair, desire and power, howling to be accepted by Sita and rejected each time, whatever he offered: kingdom or his slavedom, tenderness or lust. His Ravana’s flayed arrogance tells of the ineptitude of power and the excoriating price of desire.

My sister, Malavika Sarukkai’s stirring Bharata Natyam exposition as Hanuman etched a fundamental I held: in our imagination we constantly cross the gender divide. Hanuman inhabits the space between female and male; humankind and animal, transmitted knowledge and intuition. In Malavika’s performance, Hanuman moves from wariness — when he first spots Rama and Lakshmana in the forest — to gratitude when he surrenders to a force more immense than him, and perfect. Within the space of the song, her Hanuman changes from playful monkey to semi-divine being.Bhakti transforms him – as it can each of us, she says.

An extract from Tulisidas’s popular Hanuman Chalisa7 written in the 15th century celebrates this devotion as it recounts Hanuman’s story to himself as listener in the manner of the Ramayana itself which repeats its tale at various instances to various characters, the first of who is Ram himself.

“You are an ardent listener, always keen to listen to the narration

of Shri Ram’s life story. Your heart is filled with what Shri Ram stood for.

…With overwhelming might you destroyed the asuras and performed

With great skill all tasks Shri Ram assigned to you.

You brought the herb Sanjivan and restored Lakshman to life,

Shri Raghuvir elatedly embraced you with his heart full of joy.

Shri Raghupati jubilantly extolled your excellence and said:

“You are as dear to me as my own brother Bharat.”

“Thousands of living beings will chant hymns of your glory”

saying this Shri Ram affectionately hugs him.

Separation is the theme that runs through the Ramayana. Separation caused by death, circumstance, ideals or social mores, separation of the self from its core identity and needs. This tender-tragic mood accounts for much of its lasting appeal. One separation, however, is thwarted when Rama attempts to dissuade Sita from accompanying him to the forest. This- in my translation adapted from Malaysian poet Ponniah’s version of Kambaramayana8 — is a passage from the dialogue between the prince and princess.

Janaki, love,

you are a princess, accustomed

to the comforts of the palace.

Don’t come with me! Unaccustomed

are you to life in the forest. How

will your petal-soft feet bear the scorch

of soil burnt by sun? Or the pierce

of thorns? How will you endure

night’s freezing sheet?

The terrors of the jungle are not

meant for you, fair Princess, love.

In the version below, Sita’s answer – from the Valmiki Ramayana – is translated in the late 1800s by Ralph T. H. Griffith. The rhyme scheme formallyemphasises the Victorian decorum that circumscribe Sita’s character just as Rama’s refrain, “The wood, my love, is full of woes,” gives his earlier speech a mournful and noble quality, albeit in an Orientalised manner.

Sita … In soft low accents made reply:

“The perils of the wood, and all

The woes thou countest to appal,

Led by my love I deem not pain;

Each woe a charm, each loss a gain…

…With thee, O Ráma, I must go:

My sire’s command ordains it so.

Bereft of thee, my lonely heart

Must break, and life and I must part.”

My great aunt, known through her pen name Kumudini, wrote popular stories in Tamil in pre-independence India. An early feminist and Gandhian, Kumudini wore the traditional nine yard saris in khadi she herself spun while living in the conservative temple town of Srirangam. In her irreverent and humorous interpretation she cleverly presented Sita’s Letters 9 as a domestic saga; it’s pithily translated by Ahana Lakshmi. Kumudini insouciantly reduced the trauma of the trio leaving for vanvas into a set of frivolous letters written by Sita to her mother about the kind of sari she wants for Rama’s imminent coronation –with details about fashionable colours, silks and borders. The story ends with Sita writing,

“MOTHER, No need to send any sari. All is over. We are going to the forest. The coronation -will now be for Bharatan. The person who is bringing you this letter will tell you everything. I have only one dress made of bark-skin. If it rains in the forest I will get wet; I will have nothing else to wear. Therefore, if possible, send a bark -skin. Your son-in-law says that your applams taste heavenly. We are going to Chritakoot. Yours in haste, Sita”

Kumudini’s is a devastating upending of all versions of this episode of the Ramayana. Perhaps Kumudini’s spirit was with me when I wrote Menaka Tells Her Story. As a prelude is Griffith’s keen and melodiously rhymed rendering of Vishwamitra’s sighting of Menaka. This is in keeping with the commonly held notion of woman being a ruinous temptress. The sage is struck by the arrows of Kamadeva, God of Love, and bewitched, helplessly succumbs to her charms and falls in love, not lust.

“…The glorious son of Ku?ik saw

That peerless shape without a flaw…

He saw her in that lone retreat,

Most beautiful from head to feet,

And by Kandarpa’s might subdued

He thus addressed her as he viewed:

“Welcome, sweet nymph! O deign, I pray,

In these calm shades awhile to stay.

To me some gracious favour show,

For love has set my breast aglow.”

Pregnant Sita’s abandonment is possibly more abhorrent than the aspersions cast on her chastity after the war when she determinedly attempted immolation. Even Agni, Fire God, cannot touch her blazing virtue. This lucid and poignant translation is by Lakshmi Holmström10 :

“As if she were returning

to her palace upon the lotus

which rises above deep waters

she leapt within. At once

the fire itself was scorched

like milk-white cotton instantly ablaze

by the flames of her chastity.Agni rose up, lifting in his hands

she who had plunged into his flames,

himself burnt by her fire.

Distressed, crying out in pain

Agni bowed in worship

to the source of all wisdom.…In an instant Rama retorted,

‘And who are you? What is it

you say, rising from the fire?

You refuse to destroy this wicked woman,

praising her instead. Who

instructed you? Answer me.’‘I am Agni. I stand here

because I could not withstand

the burning flames of this lady’s

chastity. After all you have seen,

can you still doubt her, you

who are witness to all things?’

In Menaka Tells Her Story, though the apsara dutiful seduces Vishwamitra and saves the gods, she is later cursed– which leads to women being accused of seducing men when sexual crimes are committed against them. (Of course there’s a chance to rid herself and all women of this curse.) During her immortal life of wandering my Menaka recollects Sita’s descent into Earth thus:

“… Of course Rama took His duties extremely seriously, but He was mild-mannered, and a keen ecologist, as was His wife, Sita Devi. They spent no less than fourteen years in the forests. In fact, as I recall, She loved the wilderness so much that soon after Their return to Ajodhya for His Coronation, She opted to return to the forest to bring up Their twins, Lav and Kush, in this environment rather than the palace with its intrigues. The twins grew to be fine, curious adolescents. That’s when Sita Devi decided She’d done Her duty and wished for Her space; She chose to return home to Earth, Her mother… I remember still the fragrance that flowed from Earth at that moment.“

I end with excerpts from two songs by Kanakadasa and Kabir who belong to the pantheon of mystics who have sung about the Ramayana and Rama as sa-gun and nir-gun. These songs have travelled with me for decades.

Kanakadasa was a herdsman who lived in Karnataka during the Vijayanagar empire in the 1500s. It was after much struggle, first with himself and later society that he was accepted as a true bhakta by high caste Vaisnava followers. This chant-like translation by William J Jackson of the song, Yelli nodidaralli 11 is in the spirit of the bhakti movement.

Wherever I look I see Rama

Those who know the secret know

That in their own bodies they can see Rama…

O my brother, in your body

You can see Lord Rama

…Ignorant people believe in superstitious customs

Be wise, don’t have blind faith in wilderness stones

All the futile little gods waver and falter

Only our Badadakeshava truly knows

Wherever I look I see Rama

Those who know this secret know

That in their own bodies they can see Rama

Kabir, also 15th century, used sandhya bhasa /twilight language of riddles in his songs to comment on the mysteries of life and the spiritual. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra uses slang and terseness to great effect in his translation12:

Answer this and do it quickly,

If you care at all for your devotee.Who’s greater?

The lord of the universe

Or the one who made him?

The Vedas

Or their source?

The mind

Or what the mind believes in?

Rama

Or Rama’s supplicant?The question that’s killing me, says Kabir,

Is whether the pilgrim

Or the pilgrim town is greater?

Notes

1 David Shulman ‘Fire and Flood: The Testing of Sita in Kamban’s Iramavatarm quoted in Arshia Sattar’s translation ,The Ramayana, Valmiki , xxxvii, Penguin Books India, 2000

2 www.valmikiramayan.net/mhp.htm Translated by Desiraju Hanumanta Rao (Bala, Aranya and Kishkindha Kanda ) and K. M. K. Murthy (Ayodhya and Yuddha Kanda) Whenever possible, I have chosen texts available on the Net to facilitate readers’ engagement with the ‘original’ translation in its entirety.

3 Pg. 344-345, The Ramayana Valmiki, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 2000

4 http://www.valmikiramayan.net/mhp.htm

5 Paula Richman, Extraordinary Child: poems from a South Indian Devotional Genre, Penguin Classics, India , 2008

6 Adapted from http://www.valmikiramayan.net/mhp.htm

7 abbreviated from http://www.hanuman41.org/HanumanChalisaInEnglish.htm 5/3/2008

8 Malaysian poet-playwright Ponniah’s translation is available on the Net. This is an excerpt from the Ayothiya Kandam. Act II Scene VI.

9 Pg. 1, the Inner Palace A Kumudini Anthology translated by Ahana Lakshmi, publishers Srirangam Srinivasa Thathachariar Trust. Ahana Lakshmi is Kumudini’s granddaughter.

10 www.openspaceindia.org/kiskikhanani. First published in The Rapids of a Great River: The Penguin Book of Tamil Poetry, ed. Lakshmi Holmström, Subashree Krishnaswamy and K Srilata. Penguin Books India 2009

11 Pg. 214, Songs of Three Great South Indian Saints OUP. New delhi, 1988

12 Pg. 93, Songs of Kabir, New York Review of Books Classic, 2011

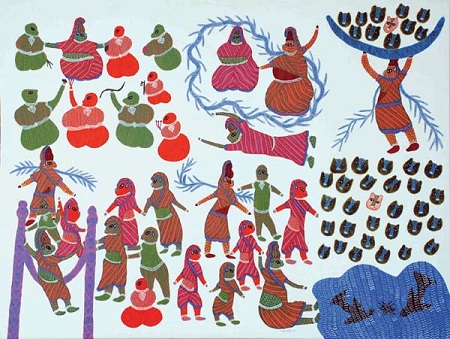

Notes: Reprinted with kind permission of author from Kiski Kahani:An Anthology of Personal Journeys with the Ramayana. CCDS, Pune. Visual: Gond Ramayani painting. Courtesy: http://shwetawrites.com/gond-ramayani-tribal-comic/Priya Sarukkai Chabria is an award winning translator, poet and writer acclaimed for her radical aesthetics. Her books include speculative fiction, literary non-fiction, two poetry collections, a novel and translations from Classical Tamil of the mystic Andal. (For a review see here:) Forthcoming publications include: (Ed.) Fafnir’s Heart World Poetry in Translation (Bombaykala Books, 2018); speculative fiction, Clone (Zubaan, 2018, University of Chicago Press, 2019); A translation of hymns from Classical Tamil. She edits Poetry at Sangam. http://poetry.sangamhouse.org/. More at: www.priyawriting.com

Leave a Reply