Somendranath Bandopadhyay

Translated by Bhaswati Ghosh

I

first arrived at Santiniketan in 1942, after clearing the Matriculation examination. That was the first time I saw Kinkarda. In time, our acquaintance grew closer through my father, who, as Kinkarda’s batch mate, was a member of Kala Bhavana’s first student body.

I saw Kinkarda and marvelled at his works during my student life. Then again, I saw him with his works on burning afternoons or in the evening’s shadow-caped deepening dark. But at that time, I didn’t have the requisite insight and maturity to know him well. In 1957, I joined Visva-Bharati as a teacher. That’s when I found him again, in a totally new way. For twenty-three years, between 1957 and 1980, my close association with him made our relationship much more intimate and deeper. I hold this fellowship and intimacy in great esteem.

However, I didn’t realise that this closeness had also gradually fostered in me an uncomfortable dissatisfaction and unease. At one point this became clear to me. Everyone knows Kinkarda as an outstanding artist—one of the finest exponents of neo-Indian art and perhaps the greatest of sculptors, whose originality is undoubted, who never wore labels of ‘East’ and ‘West’, who was independent and walked on his own path. Some see him or like to view him as a rootless Bohemian artist. His lifestyle is completely different from Western Bohemian artists; rather, he is closer to the bauls of Bengal, oblivious of worldly concerns. In this respect, I wholeheartedly agree with respected Manida (artist K.G. Subramaniam). That Kinkarda is driven by an inner force, empowered by sheer outstanding talent, resulting in the birth of extraordinary works of art isn’t the full story. He lives in a world of introspection—contemplating about the nature of life. Entwined with this is his world of artistic thinking, in itself fertile and rooted in life’s experiences.

What many of us do not know is that these experiences have been shaped by the sharp observation of his highly alert sight, the perceptions and realisations of his overly sensitive heart, his self-study and reflection, and many other influences. Benodebehari Mukhopadhyay—Ramkinkar’s batch mate and another talent of Kala Bhavana—also took up the pen besides pursuing painting. He wrote many valuable articles, criticisms, autobiographical and semi-autobiographical pieces. These reflect his analytically-rich intellectual strength as much as they highlight his experience and perceptiveness.

Kinkarda, though, never took up the pen. He did not have that mindset. Nor did he have the time. He had devoted his body, mind, life to ceaseless creation….I decided that if he would permit me to do so, I would come to him according to his wish and leisure. I would glean bit by bit, the best I could, from my interactions with him. In this way, at least some things could be preserved for those who want to know him, understand him deeply, or those who would never have the good fortune to see him, to listen to him.

Even as I was contemplating this, an unexpected opportunity came my way. At the time, Kinkarda used to stay at Shankhoda’s (artist Shankho Chowdhuri) mud house in Ratan Palli. That house was on the verge of collapsing. To my great delight, Kinkarda came to live in house number twenty in our Andrews Palli, right next to me. Without wasting any time, I grabbed this opportunity.

Morning, afternoon, evening, late evening—I visited him at all hours. On off days and holidays, a passion to leave everything aside and run to him would seize me. After nearly a year of such sessions, the work was complete.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A

fter a long day’s tiring work, a Santhal family returns home. A man carries a heavy load on his shoulders. The shoulder is rather elongated. One side of his load comprises goods and chattels, while his son sits contented on the other side. The man’s wife carries a basket on her head and a small son in her arms. With them walks another family member—their loyal dog.

Kinkarda stares at the photograph for a long while. At last he says, ‘These people took a lot of my time. I didn’t give so much time to any other work. For a single mistake, I had to put in twice the labour. How can I even call it a mistake? I tried to work economically. The woes of working cheap. Ha, ha.

‘You know what I initially did? I made a bamboo frame and fattened it with hay, then cemented it and started working. Why would it bear the weight? I had to throw away all of it. In the end, I got an armature made of iron. Now it stood strong.

‘I could see the entire sculpture in my mind. I got deeply involved with the work. Just then, I was summoned to Uttarayan. Gurudeb was directing a play—Tasher Desh, I think. He asked me to participate. I was in a tough spot. Taking part meant a whole lot of trouble. Daily rehearsals, morning through evening. And Rabindranath was extremely fastidious. One could never satisfy him. Even if he liked the acting, who knew when he would change the parts one had already memorised? Deal with that then. A whole month would go to waste. How could I find that much time? I avoided it by saying, “I have loads of work.” In the end, someone else got the part. I was saved.’

***

‘The work on Santhal Family had intoxicated me. Tell me, how could I move off it? The sculpting was in progress. I would toil day and night; had set up a tent in front of the sculpture. Back then Kashi, not Bagal, was my assistant. Later, Bagal became my companion for every work. He was too young then (at the time of Santhal Family).

‘I would work. During moments of leisure, I would smoke a bidi and look at the work. All my time would be spent in the tent. Friends would drop by. We would drink tea and chat away.

‘One night—it must have been quite late—I was working on the raised platform. Kashi was holding the lantern. The ashram was dead quiet. Just as I stopped chiselling, I noticed someone standing in the dark at a distance. No movement. I thought it was a trick of the eye and focused back on my work. After quite some time, when the lantern fell off drowsy Kashi’s hands, I started climbing down the platform. Just then I noticed the shadow-like man was moving too. When I stepped down and approached him, I was stunned. Completely dazed. I saw Mastermoshai standing there. Later I came to know that he used to come there often to see my work.

‘Since this episode, he used to come and sit in my tent at daytime too. He would have tea with me. During work, I couldn’t do without bidi. I don’t know, perhaps out of consideration for me, he asked for a bidi one day and smoked it himself. I was astonished. He only wanted to put me at ease. Otherwise, he was a reserved, serious man. So I used to maintain a distance from him. But when one interacted with him, a completely different face became visible. Compassionate, friend-like. He had two sides. Both were equally real.

‘One day, while lying alone inside the tent, I was incoherently singing some Santhal notes. And was viewing the work from a low eye-level. There’s a certain delight in seeing something against the backdrop of the sky. It has great benefits.

‘Suddenly, Mastermoshai appeared. As I got up with a start, I saw his face was overcast. He sat down beside me. Without looking at me even once, he softly said, “A river is a flowing stream. In some places, an eddy collects some hay and straw and remains stuck. It keeps circling endlessly.” Now he looked straight at me. Said, “You have got stuck too. When will your work finish? Will you remain like this forever, separated from the Kala Bhavana life?”

‘Eddy. Ha, ha; he had nicely put it. I really had got stuck, my dear. Had entered it like Abhimanyu; there was no way out. Iron, pebbles, cement, chisel, hammer—all of them had besieged me. Abhimanyu had caved in.

‘Mastermoshai’s words brought me back to my senses. Work had to be finished. Does one have infinite time on one’s hands? Leave alone the Kala Bhavana life, even my own life was rushing by. How could I remain stuck like that?’

![]()

***

Close to Santhal Family stands another monumental work. Two young Santhal women are running against a strong breeze. The ends of their saris flap by, while dust sweeps under their feet. Following them is a small boy, trying to touch the flying sari ends with his flute. The swiftness of storm zips through every limb of the stiff concrete. Both women appear to be hurricane personified. At the same time, their delight and excited smiles seem flower-like. One of them looks ahead, the other behind. Arrogance peeks out of her curved neck.

This sculpture of Kinkarda’s is called The Storm. Alternatively, it is also known as The Machine’s Song or The Machine’s Flute. The two tribal women are seen rushing to the call of the paddy husking machine.

Santhal Family and The Storm—these two works of Kinkarda’s are of two different types. Even though the first one is a moving image, that movement is distinctive. It depicts tired feet, trudging along. Complete with load on the head and shoulders; the sculpture appears to be symbolic of the weight of poverty-stricken life. The feet bite the earth in order to move on. And the work involves a lot of feet, including those of the four-legged creature.

In The Storm, on the other hand, there seems to be no meeting point between the feet and the earth. The women’s feet don’t seem to touch the ground at all. As Rabindranath puts it in his poem ‘Santhal Girl’, featured in the Bithika anthology, the women’s walking and flying become one. In the poem, the poet describes the woman thus:

Mota shari aant kore ghire achhe tonu kaalo deho.

Bidhatar bhola-mon karigor keho

Kon kaalo pakhitire gorite gorite

Shraboner meghe o torite

Upadan khunji

Oi nari rochiyachhe bujhi.

Or duti pakha

Bhitore adrishya achhe dhaka,

Loghu paye mile gechhe chol aar ora.

(A thick sari tightly wraps her dark, slim body.

One of god’s absent-minded artisans

must have lost his way while creating a black bird

and perusing ingredients from monsoon’s clouds and lightning,

fashioned that woman. Within her hide two wings,Her brisk feet merge walking and flying.)

In Kinkarda’s sculpture, however, the wings aren’t completely hidden. They become evident in the flying sari ends.

Kinkarda sits still, holding the photograph before him. His pressed lips move upwards. The contracted eyebrows and eyes tell me that his mind has flown back to the mindscape of those stormy days.

‘Working on this gave me a lot of joy, my dear. Every evening after work, I would return home and play some flute. I used to have a big Tipara flute—where did it go …’

‘This work of yours appeals a lot to us too. We like it because of its amazing vitality. There is, of course, a life-force in the women’s figures, but what really strikes me is that flower-like smile shining out of hard concrete. I remember I had seen something similar in the stones of Konark. That had stunned me too.

‘But, Kinkarda, I have a doubt. It’s been nagging me for a long time now. A number of times I’ve thought of asking you about it, but couldn’t muster the courage. Now that I have the chance, may I?’

I look at Kinkarda’s face with diffidence and see a trace of indulgence on his pleased face. Reassured, I ask the question.

‘That boy’s figure. It seems like a forced addition. I have mindfully looked at it quite a few times, just to be sure. Have tried to understand it. Somehow, its rhythm doesn’t match that of the two female figures. Even though I like that figure, I like his stance.’

Kinkarda remains silent for a long time. Perhaps he’s mulling over something with closed eyes. Or maybe in his mind’s eye, he is revolving around his creation to scrutinise it.

‘The boy’s figure has vitality too. But, I can’t dismiss your observation altogether, my dear. Nah, nah, you are right. Right you are.’

He says these words in a soft voice, with several pauses. A little later, the pitch rises. And a flash of that familiar curious smile strikes the corner of his lips.

![]()

‘Listen then.

‘Those folds of the flying sari ends behind the two women—do you know how much those weigh? Think of the amount of iron and concrete they hold. It’s very difficult to keep them flying, my dear. Painting doesn’t have such troubles. In a single brush stroke, you can give flight to a heavenly angel, sari and all. But sculpture is rather tricky, my dear. An artist has to think of these practical problems.

‘The girls’ sari ends had me totally hassled. Ha, ha. At last, I added that boy. He acts as a support. I even put my flute in the boy’s hand, which touches the sari ends.

‘I didn’t face these problems in Santhal Family. It didn’t have any complications.

‘Mastermoshai would come as I worked intently. He would quietly watch it. The sculpture was almost done. One day, while observing the work for a long time, he remarked, ‘Both your figures are looking ahead. Can’t you turn around one of the girls’ heads?’ With that remark, he left.

‘His words hit me like an arrow. This is what a true artist is all about. See, he had studied my sculpture in even more details than I had.

‘As soon as Mastermoshai left, I took up the hammer and knocked down one of the girls’ heads.

‘Later, when that girl curved her shoulder to look behind, my own head spun in wonder. Hmm, hmm.’

Kinkarda’s laughter doesn’t stop. He keeps chuckling to himself. Bursts of muffled cackle make his eyes close. As soon as the laughter ends, his face is serious again. He says in a deep voice, ‘That day I realised what a great artist Mastermoshai was. With a single suggestion, he had completely changed my sculpture. Just turning the face around added such strength to the work. The contrast of the directions of the two faces helped so much. I was astonished.’

I hadn’t seen the earlier sculpture of the girl whose head Kinkarda had demolished. But it isn’t difficult to imagine how it must have looked. Nor is it difficult to comprehend the significance of the change. In his sketches though, I have seen the mold for the older sculpture.

‘Painting and sculpture—you may think these are just two faces of art. That’s not the case, my dear. The two have completely different problems and also have totally distinct characters. Two different worlds altogether. As you keep working in both forms, you understand this only too well.’

The sculpture has been named Labour. Some call it Paddy Husking. A body is seen bending backwards, with both its hands raised and its legs apart. An object, gripped with the fists, moves down to its back, elongating across the ground. However, the figure doesn’t have a head. Is this symbolic of raw physical labour? Or does it represent a simple-minded labourer, unable to exercise his mind as a result of his circumstances?

This sculpture has now changed its position in the ashram, owing to the institution’s accommodation needs. Its present abode is at the turning of the Sriniketan-bound tar road that leads to Sangit Bhavana. Once it stood near the old Nandan building in front of the playground. Needless to say, the shifting has taken its toll on the sculpture. During the shifting, its organs had become disjointed. And in the corner of his house, a helpless artist, the creator of this art work, had spent restless hours in heart-wrenching agony.

After the necessary repairs, though, Labour has stood up once more, with both its hands outstretched.

He holds the photograph before me. A trace of sorrow appears on his face.

‘They broke it. At the time of building the Birla House. The contractor’s men took away the broken statue in a bullock cart. Nobody even asked me. No one. I never went that side. Later, a student of mine got it repaired and erected it again.

‘You know, I had worked on that one for a long time at a stretch. I used to work from morning till evening. I really enjoyed it. As the day progressed the light used to change. This helped me view the work at different times of the day. The year must have been 1945. ‘

‘You are somewhat incorrect, Kinkarda. The deed was done before that. In 1944.’

Kinkarda does not remember, neither can it be expected of him to remember—that one of the witnesses of his artwork of that period is sitting before him now.

I had arrived just a little earlier, in 1942, as a student of what was then the Siksha Bhavana or college. How could I forget the amazing snapshot that I had witnessed day after day?

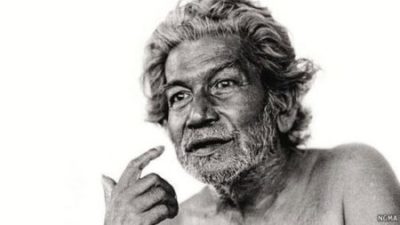

A stout man stands on an elevated iron platform, as if he himself is a statute sculpted out of stone. He wears a lungi and a shirt with the sleeves rolled up, along with a palm-leaf toka on his head. The sculpture and its creator stand face to face for hours on end. The two firm hands reveal the ceaseless urgency of the hammer and chisel.

Back then, the ashram didn’t have so many trees. Waves of red earth—Khoai—spread across the horizon. Add to that woeful water scarcity. There were times when this necessitated extending the two-month-long summer vacation. In times of drought, the temperature flared up in bursts, moving upwards of 116° F. Fire from the burning circle revolving in the sky scorched human heads. Scalding flames would breeze in from across the ruddy Khoai. And amidst the silence of such a dreadful afternoon, an absent-minded artist played with the fire of creation.

—–x—–

NotesWith kind permission Bhaswati Ghosh. Text excerpted from My Days with Ramkinkar Baij by Somendranath Bandopadhyay; Translated by Bhaswati Ghosh. Published by Niyogi Books in collaboration with National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Leave a Reply