Darius Cooper

I

n his review of Ulysses, in 1923 T.S. Eliot declared that “the novel is a form which will no longer serve” to represent the modern world. Along with other forms of literature, the novel “ended with Flaubert and with James,” not for reasons that were inherent in the literary forms themselves but because the age that was represented in them was undergoing a startling crisis and was being historically transformed into a “panorama of futility and anarchy.” If one wanted to write about this next epoch it was necessary to create a new form to do justice to it.

“The mythical method” became a way for Eliot “of controlling, ordering and giving a shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which was contemporary history.” The myth would mold and shape the history. It would function as an active form to history’s context.

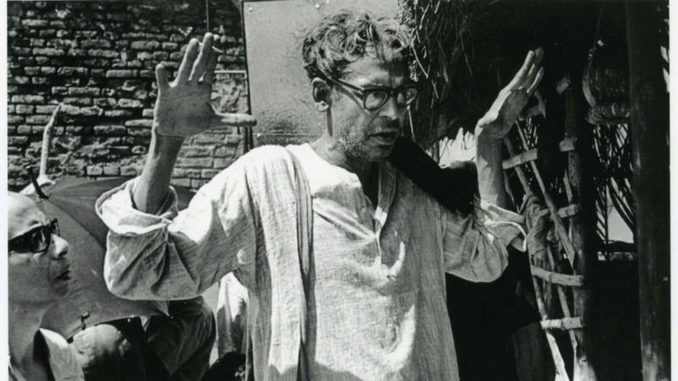

Ritwik Ghatak confronted Eliot’s dilemma in the same way in post-1947 India. “We were born in a deceived age,” he lamented because the Congress Party and the Muslim League had historically torn apart his country into a destructive independence that turned the waters of the Ganga in India red as it did the waters of the Padma in East Pakistan. Ghatak’s beloved Bengal now bore a bleeding divided presence and he could never accept its newly created partitioned history. His divided Indian families, his disturbed historical refugees, and his impoverished nomadic exiles had to be presented and investigated through their devastating history. Cinema had to become, as he said, a predominant “weapon” which he could use for this presentation. But a new method had to be found.

For Ghatak art had to be presented on three or even more than three levels. At the primary level, a straight forward conventional classical narrative (in its full Aristotelian sense) would produce laughter and tears. At a slightly deeper level, it would excavate certain social and political implications, and deeper still it would confront serious philosophical tones and undertones. If the artist, in a determined mode of self-awareness, chose to go even deeper, he could reach those moments that Joyce called “epiphanies” and Ghatak called “the threshold of the unknown.” And the one method that Ghatak felt which would enable the artist to touch all of these different levels was the mythic method which would assume the all-important form that would enable the artist to control, order, and assign a shape and a significance to the epoch and culture being depicted as historical content. It would also display, on one hand, the consciousness of the artist as an activist and at the same time also allow the other consciousness lurking closely behind to manifest itself, which was that of the artist as a visionary. While the former would force the artist to confront his historical material in a determinedly tough minded way, the latter would allow the flowering of the tender minded human impulse. And it was here that the archetype manifested itself so clearly and so convincingly for Ghatak.

The fundamental traits of contemporary historical reality for Ghatak could only be portrayed through his characters slowly embracing and becoming abstracted archetypal figures who would then progressively demand from us an archetypal reaction, for not only was their history tortured but their existential sense of being was archetypically bisected as well. Bimal, the cabdriver of Ajantrik is wondrously arrested as a child in his grownup universe of cabdrivers and garage mechanics. And his best friend is not a human being but his old cab that he fancies he is permanently married to. Neeta in Meghey Dhaka Tara becomes and perpetuates the benevolent Durga or Jagadhatri, whilst her mother rages as the destructive presence of Chandi, and in between is offered the sensual extension of the female in the unprincipled presence of the cunning younger sister Geeta. Seeta’s femininity in Subarnarekha is trapped in the archetype of mother and sister that enables her to look after her brother Ishwar, but when she tries to play the roles of a wife and mother in her eloped exile in the big city, the foul archetype of the polluted whore is imposed upon her after the cruel city murders her husband. And when this desperate archetype is confronted by her roaring drunken brother, a self-inflicted death is the only liberation that she can finally succumb to.

In Jukti Takko Ar Gappo, Nilakantha’s name is offered as an allegorical archetype. When the gods churned the oceans in search of the elixir of life many strange things came out of the waters. One of them was poison so lord Shiva took it upon itself to drink it before it could contaminate the world. The poison made his throat blue. Hence he was called the blue-throated one. But Ghatak’s Nilakantha is also Eliot’s Hollow Man from The Wasteland. It is not only his drinking that has rendered him one dimensionally blue. As he has swallowed, on a daily basis, the poison the history of his time has offered him so repeatedly, his life has been historically wasted. So he drinks to waste it further because life has no meanings to offer him anymore. He waits only for death to complete it. And when death arrives, his final gesture is to soak it with alcohol.

What is striking about Ghatak’s cinema is its enormous weightage of mythical references. He extracts certain elements as fragments which are capable of performing interesting functions. In doing so they draw attention to the fossilized evidence of the history of a country that was so cruelly partitioned as fragments themselves. The mythical method that he employs again and again reorganizes this tragic history giving us an honest and often painful understanding of it.

In Subarnarekha the abandoned runway of a defunct aerodrome is presented as a dramatic witness to the horrific devastation of World War II. He juxtaposes that tragedy with the archetypal form of the Bohurupee character that young Seeta has a sudden encounter with. In reality, the Bohurupee is only a poor travelling actor who amuses people by adopting the persona of the Goddess Kali. But Seeta is frightened by his disguise. Her singing is not only rudely interrupted, but it is replaced by a new chorus of screaming that plunges her into the arms of the foundry manager who earnestly tries to calm her hysteria down. Alarmed by her response, the Bohurupee retreats murmuring, “I didn’t want to scare her. The little girl just came in my way.”

Here, destruction and innocence are made to collide in interesting ways. The Kali archetype summons on one level the destruction that man is capable of inflicting on his fellowman, be it the deadly bombs dropped on Hirshima and Nagasaki or today’s nuclear missiles in the hands of power-crazy leaders or even the genocidal cleansing of minorities in so many prts of the world. It is this power to annihilate and destroy that really confronts and scares Seeta. It interrupts her singing and interferes with her carefree innocence. She flees as a mute witness, straight into the arms of an older man who wanders on this dissolute airstrip searching for his daughter who has run away from home. Seeta will run away from her home as well and her brother will be rendered homeless exactly like this old man. The sequence powerfully confirms all the bombs human beings drop on each other once their personas are torn off.

In Meghe Dhaka Tara, the airstrip of the previous film is replaced by the family courtyard. This becomes the film’s powerful fragment mythically associated with Neeta’s constant victimization at the hands of her rapacious family. The one ceremony that is habitually performed in the courtyard is the sacred fire of the havan, meant to commemorate the ending of all bad occasions and the revival of all the good ones to come. So mortal offerings are consigned to its flames and offered as sacrifices by the priest on behalf of the unlucky and grieving family. This symbolizes the surrender of all ill-fated human desires and selfish aspirations; and out of its smoke Durga is born in the form of Jagadhatri.

On a realistic level, but mimicking closely the mythological one, especially in powerful ironic ways, the selfish aspirations of Neeta’s family are now presented by Ghatak as being routinely poured all over her in this very same courtyard: Shankar’s desire for a shave; Montu’s for his football shoes; and Geeta’s for her sari. But the most devastating are her mother’s whiplash demands for cooking oil and ghee for the daily preparation of the family meals. All prey upon Neeta, the minute she steps foot into the courtyard from an exhausting day of work and by the time they have finished with her, she is left completely emptied and stranded, all alone, in the center because she willingly surrenders to their assault. She is repeatedly marginalized and overwhelmingly pushed to the courtyard’s periphery and she offers no resistance. And once tuberculosis becomes her body’s permanent tenant, her utility is no longer needed. She is banished to her own room where she is compelled to hide her bloody handkerchiefs while her family in the courtyard dreams of adding an upper floor with the money now earned by her prodigal elder brother Shankar who was once spat upon and exiled from this very same courtyard but is now welcomed and eagerly fawned upon.

The mythical and the real again collide most cruelly in the deterministic policy of the family’s cruel mother. Associated with the menacing sounds of rice boiling in her kitchen (the family’s staple surviving food), the mother perpetuates the image of Chandi, the evil mother archetype, preying sacrificially upon Neeta to sustain the lives of her other family members. Threatened by the prospect of Neeta marrying Sanat and leaving her family courtyard for good, she callously encourages her voluptuous younger daughter Geeta to seduce the helpless Sanat when he comes to meet Neeta. When her incapacitated husband intervenes, she snaps at him. “What will we eat if Neeta leaves?” And she doesn’t stop here. Overcome completely by her evil archetype persona, she succeeds in having Neeta surrender her entire dowry jewelry to Geeta on her wedding day. This “dark” deed is accomplished with a cruel reminder to the completely scalped Neeta that she is too “dark skinned” anyway to tempt any new suitors in the future. And when tuberculosis becomes Neeta’s new suitor, the mother’s victory is completely achieved on both the realistic and archetypal levels.

The sacrifice of individuality plays a crucial role in Ghatak’s epic method presentation. The individual sinks into an archetype absolute from which she and he can never free themselves. This highly mythic reabsorption by such a blinding totality is for Ghatak the only historical process worthy of being tragically maintained. Neeta’s sacrifice is presented not as a dharma or duty but as a sin. Neeta herself acknowledges this to Sanat when he comes to her after his disastrous marriage asking for forgiveness. And it is this acknowledgment of her sin that powerfully prompts from her, as she is dying a violent assertion to live even when she knows it is too late. Only her brother is shown, in the film’s final mythical scene, reconciling himself with horror, not only to Neeta’s personal loss but also the loss of the second Neeta who Ghatak powerfully introduces here: the grocer’s ironic moving epitaph of Neeta. “Such a quiet girl. Nobody will miss her.” This second Neeta is a carefully chosen fragment whose function is to signify the sacrifice of not just one Neeta but several Neetas. It commences with them breaking the straps of their slippers and ends with them coughing blood in their rooms in the rare but hopeless altitudes of hills in an overwhelming indifferent landscape of mother nature.

Seeta’s suicide in Subarnarekha is offered as a sacrifice to her drunken brother as well. It is the only tragic response she can leave behind on a mythic level to counter the fossilized evidence of Ishwar’s cruel individual family history that confronts them in their final encounter so tragically and so realistically not as a sister and a brother but as a whore and a client. Its function opens Ishwar’s eyes towards the formation of a new family with her child Binu who witnesses this horrific scene. From the shattered debris of his family history, the mythical enactment of the mother/sister’s archetype death will hopefully enable Ishwar to reconstruct a new history for himself and for her son.

Change is in the air throughout the cinematic climate portrayed by Ghatak in Ajantrik. The ancient agrarian tribal society of Bihar is shown moving towards rapid industrialization. Similarly, like all ancient machines, Jaggadal will one day conk out and die, but life for its grieving master Bimal will have to continue after the sacrifice of his beloved machine. The fragment that introduces this new future is found in the film’s last scene. A boy is shown playing with Jaggadal’s discarded horn. Its sounds function as a nostalgic entrance into an unknown future. The smiles exchanged by the child and Bimal acknowledge that. It commemorates Bimal’s final mythical epitaph as the scrap dealer hauls away the remains of his beloved machine. “Go dear friend. You’ve fed and clothed me long enough. After all you can’t do it forever.” Jaggadal is still humanized as her headlights, suddenly reflecting the sunlight on her hearse-like cart seem to give Bimal a last naughty wink.

While the nexus between man and machine on a realistic historical level has always been problematic and even monstrous in many cases, on a mythical anthropocentric level it can be, as Ghatak shows us in this charming film, to be significant and inevitable. Its philosophical implications cannot be erased by history because the mythic method will not allow this pathetic fallacy to be extinguished in any realistic way.

In Jukti Takko Aar Gappo, history is mythically achieved by Ghatak, on the alcoholic level. What flows inside this Nilukantha is not only blood but a steady stream of alcohol. As a part of his epic method we have seen Ghatak retain the alcoholic fragments, and, in fact, in many of his earlier films, he enlarges their presentation through their mythical functions. In Ajantrik, alcohol not only ushers Bimal frequently into the tribal Oraon’s community, but fosters a permanent bond with them. They share their food and their drinks with him when the harsh world of reality demands his exile. In Subarnarekha alcohol’s desperate flow, accompanied by Fellini’s Patrica melody, forces Ishwar to confront his guilt of breaking up his family and rendering him alone like his equally drunk and desperate friend Hariprasad who had driven his wife and children to suicide as well. When his sister, in her resurrected archetypal role of the whore confronts him and in response commits suicide, he can only receive her sacrifice through the consummate gaze of a grieving alcoholic, and his howl of despair becomes the appropriate closure to his inevitable mourning.

In Jukti…the persistent presence of alcohol within him makes Nilakantha react simultaneously not only as the child and the parent but also as the wise man and the fool. The protean fragments that accompany each of these assumptions make him function as a historical and a mythical subject. When he dies, struck down by a stray bullet in history, his response to his death is predominantly mythical. He splashes and smears Ghatak’s camera lens with streams of alcohol. His death, by this mythical gesture, is suddenly emptied here of all existential meanings. It is offered on a purely mythical level that endorses also his final words to his wife. Just as the weaver in that mystical story was running an empty loom because he had to do something, Nilakantha offers his own epitaph washed conspicuously in alcohol which was the one permanent essence he never deviated from. If nothing was achieved realistically by Nilakantha, his final gesture on the mythical level, bears all the signs of his svardharma.

This places him as a specific subject beyond history. It is as if Ghatak (who played Nilakantha) is arranging his own death and in order to do so the mythical method that he had rigorously followed and the alcohol that he had persistently consumed helps him achieve his final salvation, not only from within history, but above and beyond, in fact, way beyond, history itself.

Notes. T.S. Eliot, “Ulysses: Order and Myth”. http://openmods.uvic.ca/islandora/object/uvic%3A64/datastream/PDF/viewDarius Cooper teaches Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books). Read his review of Kedarnath Singh's poetry 'BETWEEN THUMBPRINTS AND SIGNATURES'. Also, read his essay on Coming Home to Plato's Cave in Personal Notes.

Leave a Reply