May 7 marked Rabindranath Tagore’s 157th birth anniversary. Celebrations were held not just in India but in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka as well, two countries that historically and culturally may have had affinities with India but that also have strong ‘nationalist’ sentiments couching grievances that have erupted time and again or mutely underlined their interactions with ‘big brother’ India in the recent past. So how was it that Tagore, India’s ‘national’ poet was feted in both countries? In part, a common language, Bangla may help explain the celebrations in Dhaka. A more probable reason is that Tagore wrote and scored the national anthem of Bangladesh, and is supposed to have been associated with the music for the Sri Lankan national anthem composed by a Sri Lankan disciple of his at Shantiniketan. That, along with the fact of having composed and scored India’s national anthem and scored ‘Vande Mataram’ should render him, as Ashis Nandy has pointed out, the most unique poet of the modern nation-state.

Perhaps there is a more profound reason for the pan-Asian celebration of Tagore’s birth anniversary. Perhaps it was a transcendental leap away from the modern idea of nationhood to other selves, rooted in memories; a harkening to an a-political self, a self rooted in a more contemplative mode of existence where poetry and song and culture play a binding role creating an indivisible ‘country of communities’. And perhaps this republic’s founding fathers had been Tagore and Gandhi who had disdained “nationalism” while fighting for a free and sovereign India. .

It was this exquisite paradox that drove us at The Beacon to the “conversation” that S. Gopalakrishnan had had with Ashis Nandy some years ago on the platform Sahapedia.

As we read through the ‘conversation’ that is really an interview we realized that Nandy was in fact offering us a glimpse into a “culture of conversation” expressed in the polyphonic voices of Tagore and Gandhi as they contemplated, wrote about and acted on matters that concerned them in the years leading up to India’s freedom from formal British rule.

These issues at first glance appear peripheral today, issues that the transfer of power and seventy years of Independence may have settled. They have not.

In this interview, the conversation between Tagore and Gandhi reflect differences and affinities both of which are crucial to their respective pursuits of truths that lie beneath the facts of our formal sovereignty, embrace of materiality and their attendant discourses that continue to shape our lives.

Tagore and Gandhi as Nandy tells us travelled different roads towards what would become shared visions; the mass politician who mapped the “magic of ordinariness” and the poet who “saw the human potentialities inherent in this civilization” were not the saint and national poet that they have been made out to be but creators of new ways of seeing and living; ways we have consistently ignored by deifying them.

What are the elements of their shared visions that emerge through their conversation? Doubts about ‘nationalism’ to be sure. Both believed in a ”country of communities” though Tagore was perhaps the more articulate in his condemnation of nationalism as is evident among others, in his three political novels. A strong critique of the West expresses itself through his embrace of the “other self of Europe” whose representatives were Tolstoy among others; and, as Nandy reminds us, Tagore came close to a Gandhian critique of the West in his last work at the outset of the Second World War.

The centrality of the village; both were not of the village but both were the “first theorists of the city as well as the city’s relationship with the village.” Both travelled different routes to the idea of a native genius of what Nandy terms “Indian interpreters of the world.” Both Tagore and Gandhi felt Indian unity was to be built not on the Vedas an Upanishads but on medieval sants, poetry and spiritual quests not to mention ambiguous religious and sect identities of the time.

A strong distrust of the concept of nationalism, the focus on rurality as a healing self, the willingness to critique the homogenizing materiality of the West and acceptance of its other selves, the recognition and embrace of medieval India for what it truly was, the golden age of creative confluences with its porous boundary of faiths and identities; and, running interstitially through all their life-work, a reminder that humanness is enriched by both the active and contemplative life, that modernity can pauperize the contemplative and so destroy the plurality of human experience—these are the legacies of the two founding fathers of a republic waiting to be born.–The Beacon

S.Gopalakrishnan: How do you address Tagore’s concept of nationalism which seems contradictory to many people?

Ashis Nandy: Well, a lot of people look very internally inconsistent. To a lot of people, it will seem an inner contradiction, as if Tagore did not know his mind because there are thousands of people who went to jail or marched in demonstrations singing Tagore songs. He has not only written our national anthem, Jana Gana Mana, he has also scored Vande Mataram. But I want to distinguish between patriotism and nationalism.

Tagore was a patriot. Patriotism means love for one’s country—a sense of territoriality. This is not only common to humankind. You see it in many species other than the Homo sapiens. You see it in dogs, cats even in birds. That is territoriality. Patriotism is a form of territoriality—a certain emotional attachment to the place of one’s birth, the place where you have grown up, place that frames your earliest memories. Nationalism is different. Nationalism is not a sentiment. It is an ideology. It is based on the idea of that nation.

Tagore believed that India was a country of communities. It was not a country of a nation. So trying to build a nation in India was like an attempt to build a navy in Switzerland, that is what he wrote. Because nation and nationalism presumes that you homogenise the population. And give them a theory of love of the country which also specified enemies and friends, allies and detractors. It also presumes that you will give priority to the nation over everything else. You are first an Indian, then a Hindu. You are first an Indian, then a Muslim or a Sikh. But then the answer to that is what Khan Wali Khan, Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s son, said in a Pakistani court. He said, ‘My Lord, I am a Pakistani for 45 years, Muslim for 1400 years and a Pathan for 5000 years’. So he knew that he has multiple selves and some selves will often have priority over other selves.

Nation claims absolute priority, communities do not. The traditional identity of India does not. And to that extent, there is an intrinsic incompatibility between the idea of nation and the Indian concept of self. But then a lot of Indians are now urban, westernized, middle class Indians. And to them, the nation seems an absolute must, a necessary ingredient of nationalism and nationality which defines a nation-state because what we are trying to run is a modern nation-state. That is the more modern concept of state that it must be built on nationality and nationalism.

Sometimes states are multi-national; Indians don’t want to accept that. They claim to be one nation. And if you object, they say what they say in the case of secularism. They say our concept of nation is different, our concept of secularism is different, but ultimately in practice it often boils down to the same thing. And my feeling is this that Tagore’s hostility to nationalism came from the awareness that the nation state system and the idea of nation and nationality and nationalism were totally incongruent with Indian self-definition and went against the basic principle on which the Indic civilization as well as Indian unity as such is organised. So that is the background of Tagore’s criticism of nationalism. That criticism was not lightweight. He believed in it strongly.

When he went to Japan, for example, he noticed the delirium of nationality from which they were suffering and delivered his famous series of lectures there. The result was this that when he landed in Japan, there were tens of thousands to welcome him. This was soon after he won the Nobel Prize. He was the first Asian to win the Nobel prize.

And the Japanese covered his visit, the newspapers covered his visit like royal visit. But as he went on giving his lectures, they were deeply disturbed and hostile. When he left Japan, there was only one person to see him off, his host. And roughly similar things happened in China too because these were countries which were like India, experiencing the might of Europe and they felt that their salvation lay in European style nation-states and that is what they must have.

But Tagore felt as he spelt out in all his three political novels (Gora [1909]; GhareBaire [1916] and Char Adhyay [1934]), that that would be a poisoned victory because in the course of that victory against West, you have become like the West. You have lost your culture, you have become deracinated, you have lost yourself actually. And what you will live with is a pale version of European culture sold to you as a basic ingredient of modernity. That was his position. And he never deviated from it. All his three political novels in some way or other bring in the issue of nationalism and violence and in all of them, he is absolutely clear which side of the fence he stands. There is no way you can whitewash this and sell him as a nationalist.

And people unconsciously know this. They might not admit it but they know this. Tagore is the only person in the 350 years of the history of nation-states who has been associated with four national anthems. Nobody has written more than one national anthem. Tagore is associated with four. He wrote and scored Jana Gana Mana. He did not write but he scored Vande Mataram. He did not write but scored the national anthem of Sri Lanka. And he wrote and scored the national anthem of Bangladesh. This is a record I don’t think will be broken even in the future of nation states. This is a world record if I may put it that way. And I think we have reasons to be proud that somehow implicitly it is accepted that Tagore belongs to no nation.

He was an Indian, he was a Bengali, he was a Hindu but he was also a Brahmo, a reformist sect which borrowed a lot from Islam and Christianity. And in some fundamental sense, he belongs to everybody. Somehow or other this is accepted in the case of Gandhi but this is not accepted in the case of Tagore.

S.G.:How do you compare Tagore’s concept of nationalism and his sense of patriotism with that of Gandhi?

A.N.:Gandhi’s nationalism was not very strong either. In this 90-volume collected works, there are hardly a dozen or so references in the index to nationalism though it comes out indirectly in many places but I would suspect that most cases you can see that he is actually talking about patriotism, not about nationalism as an ideology.

I suspect that the Tagore–Gandhi differences have been played up in the 70 years because we want to play up Tagore as a modern Indian. Modern Indians have been desperately looking for a great hero and not finding anyone, Tagore probably serves that purpose for them to some extent.

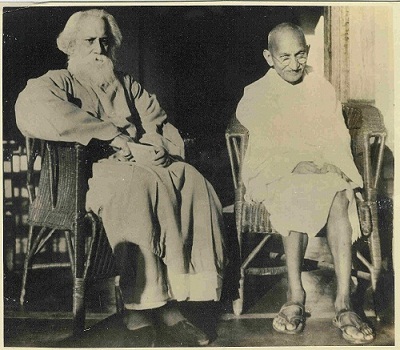

Actually, strange though it might seem to you, Tagore was writing about Gandhi even before he had heard of Gandhi, even before Gandhi emerged in the Indian scene, when Gandhi was an incipient idea. In other sense, he was anticipating the emergence of somebody like Gandhi in Indian political scene and there is a lovely essay by the late Sisir Kumar Das, himself a writer and a historian of literature, where he shows how Gandhi met this unfulfilled ambition of Tagore, to see in his lifetime, the emergence of somebody like Gandhi in the Indian public sphere. And Tagore was the one who called Gandhi ‘Mahatma’ for the first time. Gandhi called him ‘Gurudev’. And Tagore wanted to leave his alternative university Viswabharati at Santiniketan with Gandhi. He wanted him to take care of it after his death. Gandhi was younger than Tagore. And I don’t think that is an accident because even the vision of that alternative university is partly influenced by Gandhi. Gandhi was trying to practice, atleast play with the same ideas and there was a continuity between Gandhi’s NaiTalim and Tagore’s Visvabharati.

S.G.: You mentioned Tagore’s visits to Japan and the Far East. Can it be argued that Tagore was more Asian than Gandhi as the latter drew upon a lot of Western ( or, European) philosophy in his thought?

A.N: Yes, you are right,Tagore was probably more consciously Asian. He was deeply perturbed that the pre-colonial ties with India’s neighbours that had existed for centuries had collapsed. That even if we have to dialogue with your neighbours, you have to go through the western university system, a western language and western mediation and that he considered a real loss. And in Santiniketan, he tried to take care of that and India’s first department of Chinese Studies was established there. It is true. His dance bears the imprint of Sri Lankan dances .

But the fact remains that Gandhi also was not entirely a product of India. He was a product of India and Africa. His most formative years, he spent in South Africa. Satyagraha emerged in a racist country. Many people believe that satyagraha could have only emerged under a liberal dispensation, only under British rule. That is not true.It was tried out in a country which was openly racist and was a police state in every sense.

In that sense, Gandhi also had his exposure to different kinds of cultural plurality. And if you read accounts of Gandhi in South Africa, you have no reason to feel ashamed as an Indian because there is no touch of racism in him. Indeed, Nelson Mandela has said that you sent us a barrister, we sent you back a saint. And it is also true that the three greatest Gandhians at this moment, none is an Indian. None is an Indian, no one is a Hindu either or a Jain. Aung San Suu Kyi, Nelson Mandela and the Dalai Lama. And I think it also talks of a different kind of cross cultural sensitivity.

Both Tagore and Gandhi, in some sense thought not of only of India but you might say that they tried to envision a world where India would have its rightful place but so would every society, every culture and every civilisation also have its rightful place. There would be no hierarchy amongst civilisations and cultures. That was their attempt.

Within that, I think Tagore by his upbringing was perhaps more sanitised in the sense that he lived a sanitised life. That was his background and by his vocation too, (there was a) slight distance or isolation from the heat and dust of the Indian village. He talked of the village, he talked of rurality but his touch with the reality of Indian village, with the destitution and poverty that had begun to enter Indian villages was perhaps weaker than Gandhi’s.

Gandhi was after all a mass politician. Let us not forget that part of the story. Gandhi also came from a background in some ways similar to Tagore. If you look at his backgrounds, his education, he was not from village India. He encountered Indian village in his middle years. Tagore atleast had encountered the village early in his life through his zamindari in what is now Bangladesh.

.Gandhi encountered it later because for his education he went to Indian cities and then to the West, went to London.

But both retained the capacity to use the Indian village as a component of their utopias—as a corrective to the excesses of the Indian urban imagination which had no place any more for a village.

Traditional Indian cities and villages were complementary to each other. The colonial city was in negation of the village. And the village to them seemed a negation of the colonial city, to these urbane Indians. Both fought against them, both knew that you have to build into, build the Indian village in your vision of a good society. Not to turn India into a village utopia but atleast as a living standing criticism of some elements of urban life and as a corrective to its excesses.

Both of them were the first theorists of the city as well as the city’s relationship with the village.

S.G.: How does one look at the inter-relationship of Tagore, Tolstoy and Gandhi? Can it be seen as a triangle constituting a universal point of view?

A.N.: It is not really a triangle. It is an attempt in both of them to keep in touch with the other self of Europe; Gandhi even more so than Tagore, because Gandhi was fighting Europe, Gandhi was fighting the West in the form of an imperial power on the ground. And he thought a necessary part of non-violent struggle was that he had to keep in touch with western dissenters who negated the stereotyped concept of the West in many Indians as an oppressive power only. Western civilisation also has its other self which it has abrogated and now claims to have superseded. Tolstoy represented that best. So did number of others.

The west doesn’t end with the enlightenment and the positivist part of the Greek civilisation. It also had Pythagoras, starting from Pythagoras all the way down to people like Blake and others who took a position against urban industrial civilisation. A robust criticism of the kind which Gandhi was looking for and so too Tagore.

If you read his last book of Tagore, he clearly had travelled a long way towards the Gandhian critique of the West. He says in great sadness that one time I thought the new world civilisation will perhaps begin to take shape in the West. Now I believe that that is not possible. Just in the beginnings of the Second World War.

So I think instead of looking at this relationship between Gandhi and Tagore as the meeting point of two radically different kinds of public awareness I would perhaps say that everything said, there is an attempt to displace Gandhi as a relevant public figure in globalising India and have relatively more apolitical, more manageable person in Tagore.

Gandhi has already been shelved and the way it has done is to call him a saint and to put him on a pedestal claiming that this is a height of saintliness and ethics that we cannot approximate and which has no place in contemporary statecraft.

That is why the great Gandhians are now outside India. They did not give up their faith in Gandhi.

S.G.: How far was Tagore connected with the Muslim masses?

A.N.: His zamindari was East Bengal. So he must have been in touch with the Muslim masses but how deep was the touch I cannot say and I don’t believe that it was very deep. It was not perhaps as deep as many like to believe. But with the Muslim middle class yes, because he was a writer, everything said, and he was in touch with it and you cannot avoid, majority of Bengalis are Muslims.

And his family also were heavily exposed to Islam. It is not that, he had that kind of family background if you look at it.

S.G.: It is said that Gandhi claimed the Pathans were very brave persons. What is your comment on it?

A.N.: He has said this in many ways earlier that the Pathanswere the best satyagrahis in India too because the British particularly treated them very nastily because they had fought four Afghan wars. But not one Pathan picked up a stick.

Apart from that, the first announcement of militant non-violence, that is the way to translate satyagraha, I believe, in South Africa, was made by a Muslim friend of Gandhi. Then they were a triumvirate. It was first published by a Muslim editor. Of the triumvirate, two were Muslims, one was a Hindu.

So there was this linkage from the beginning; even in Tagore. I don’t think his experience would not have encompassed Islam. In a meaningful way, it did. Otherwise nobody could claim, like Tagore and Gandhi both did—that Indian unity is not built on the Vedas and the Upanishads.

It is built on the medieval santsand their kind of spirituality because the medieval sants had ambiguous religious as well as sect identities and India has thrived on those ambiguities. That has been its traditional cultural strength.

In fact, I would say that this is the way it has been in a large part of Asia and Africa, from Japan all the way to the west coast of Africa, that you can have more than one religion, you can have porous boundaries of faiths, you can share places of worship, rituals and customs with other faiths, other sects and so on and so forth

S.G.: How do you see the famous rejoinder by Tagore to Gandhi’s comment on the earthquake ? Gandhi attributed the 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake to untouchability which led to a public debate with Tagore.

A.N.: Yes, many people asked me that question and I think no easy answer is possible. At one plane, both of them differed radically on that issue. At another plane, Tagore underestimated Gandhi’s philosophical position. Gandhi was looking most probably for something like a collective karma which he believed determined the faith of communities, cultures and civilisations. A bit like Simone Weil, as the late Ramchandra Gandhi pointed out to me. There are similarities in that search.

It was not a lightweight search and it cannot be dismissed by saying that he was trying to promote superstitions and supporting the caste system.

It would be a pity if we underestimated the nature of Gandhi’s quest. I think he was serious in his quest for a spiritual position as well as a political position which would be mutually potentiating and uphold the concept of ethics in politics which you would not find in contemporary cultures or politics. (emphasis added)Certainly not within the enlightened vision of a good society. Because enlightened vision has no strong theory of non-violence. It has a theory of containment of violence but not non-violence.

S.G.: How did Gandhi and Tagore engage with the question of ‘modernity’ and ‘tradition’? Can it be argued that Gandhi’s relation with Tagore has been otherwise ignored due to the afore-mentioned public debate between them?

A.N.: Yes, that is my feeling; the real connect between the two have been missed because Gandhi was a celebration of an ordinary Indian living his ordinary life and trying to capture the magic of that ordinariness. That was his starting point. Tagore’s starting point was, I would say, the human potentialities inherent in this civilisation and how it could actualise it—try and win over its political plight as a colonial subject nation at that point of time. So I think the starting points are different but the deeper connection was much stronger than people believe. And I suspect this is because they were both open to the native genius of what you might call Indian interpreters of the world as it lived in the hearts of people. That is why both of them did not locate Indian unity in the Vedas and the Upanishads.

Both of them located it in medieval India, which contrary to the European belief and contrary to the belief of modern Indians who used the term medieval glibly and indiscriminately, medieval India was the golden age of India.

Our finest music, poetry and spiritual quests have their beginnings in medieval India. And there is nothing like the Dark Ages of Europe in medieval India. We have reasons to be proud of our medievalism.

S.G.: When it comes to the education and philosophy of Tagore, one may cite the example of how he sent one person to Kerala to learn Kathakali and the way he took Kathakali to Santiniketan not as an art form but as a tool for education. Again, such an example demonstrates that he took the best from all over the continent—the art forms, the music—for educating the masses for the new generation as preparatory tools.

A.N.: I would avoid the expression ‘the best from everywhere’. That is what the politicians say when they introduce Tagore while inaugurating a seminar. We don’t have to go by that. Both Tagore and Gandhi have—I won’t say very clear-cut—but very well developed visions of what a good society should be like and whatever they thought was congruent with that vision, they took that, not the ‘best.’ Tagore never tried to introduce the ballad into India or never tried to write an opera.

And though he would have agreed probably that Shakespeare was a great poet, I do not see much significance being given to the works of the best in the world. I see more significance being given to bring in and deepen the knowledge of India’s neighbouring countries, deepen the knowledge of all kinds of art forms which are culturally very typical, which have the capacity of telling something to the audience without too many words.

Amongst the dance forms, Kathakali’s richness perhaps lies in its capacity to be a narrative also. So he had readied himself for it because he wrote verse-plays himself and when he wrote them, the idea was to carry his words forward. He should have allowed more freedom to performers. That would have enriched music. He was afraid that they would not be able to convey the significance of the words if they were allowed to play with the composition. But I can see why he said that. I can understand why he was saying that. I may not agree with him. That is different.

———————– —————

Notes: --Excerpts from Interview conducted in 2012 for Sahapedia[5], an open encyclopedia on Indian culture and history, by S.Gopalakrishnan. https://www.sahapedia.org/tagore-nationalism-conversation-prof-ashis-nandy. --The interview appeared in the original under the tile: Tagore on Nationalism: In Conversation with Prof. AshisNandy. S. Gopalakrishnan interviews Prof. Ashis Nandy on Rabindranath Tagore in 2012

Leave a Reply