Priya Sarukkai Chabria talks with Mrinalini Harchandrai about her obsession with Andal’s poetry that led to a unique translation project with Ravi Shankar. “Sangam poetics” allows her to offer multiple versions of the goddess-poet’s songs of sacred-erotic love.

“I was drawn to her. She was the teen icon of every bride,” says poet, editor and translator Priya Sarukkai Chabria of her most recent muse. In a unique project with Indian-American co-translator, poet and editor Ravi Shankar — Priya dove into her Tamil roots to the pearlescent verses of Andal, a girl-turned-goddess whose chants she grew up listening to. Andal’s texts from the original old-Tamil are rendered into English by Priya and Ravi, and the delivery is full of the lushness that only a poet translating another can recreate.

“Eyes citrine in the dark, stretch your muscled majesty/and roar, tossing your mane like a ring of dark flame/ascend your lion throne…” (Tiruppavai, translation by Priya, p 14).

The only female Alvar saint out of 12 in the Vaishnava tradition, Andal is hyphenated as a poet-mystic since the authorship of the Tiruppavai and Nacciyar Tirumoli is attributed to her. In these two medieval-era oeuvres, filled with “garlands of verses”, we learn that she was adopted by the Alvar saint Periyalvar; referred to as Kotai – meaning ‘garland’ – as a young girl she was intensely devoted to Perumal, as Vishnu is addressed in Tamil. She was later given the name Andal – meaning ‘one who possesses the lord’ – when she united with the divine light of her god in the sanctum of the Srivilliputhur Arulmigu Andal Temple.

For someone quite young and not yet out of her teens when this happened, Andal’s pasurams or verses set to music show us that she didn’t follow the usual route for a girl her age in the 9th century, when she is said to have lived. She shunned marriage, and took to poetry that is full of bursting ardour for her lord, marked by an intensely sexual devotion, unconventional for a bhakti poet –

“My surging breasts long to leap to the touch/of his hand which holds aloft the flaming discus/and the conch” (Nacciyar Tirumoli, ‘The Song To Kamadeva, God of Love’, translation by Ravi, p 30).

Priya explains, “For Andal, the body is the site of the sacred. She sees it as completely organic and she wants to have herself tied so closely to her lord the beloved. She wants her chest so tightly bound to his that not a thread of air passes between them, metaphorically and literally.”

Although she may not be as famous as the trinity of Durga, Lakshmi and Saraswati, Andal is regarded as an emanation of the earth goddess Bhu Devi in Tamil culture. In the winter Margazhi season, discourses on her works take place in South Indian temples around the country and her songs are chanted.

II

H

aving two translators on the project was a spur-of-the-moment decision says Priya, “I was in New York and over lunch when I told Ravi that I was translating Andal, he asked to be a part of it. I love his poetry so I said yes.” Priya was tantalized by the idea of a gender-balance perspective. “I thought it would be fascinating to have a man and a woman do the translation. Being a man, he sees her physicality differently. When translating a description of her breasts he calls them ‘upturned flowers’, he sees beauty. Whereas I see them as ‘full hills’, since I think of fertility. Or where he sees red petals quite literally in a description, I will see menstruation.”

Two interpretations didn’t seem to pose a problem for the two translators. And in fact, in several areas where they pulled radically different versions out of their bags, they celebrate this by offering both to the reader.

“Andal presents herself to us in many ways, voices and ages. Each of her verses is like a seed full of potential, which grows, spreads out and splays its colours onto the sky and the earth. Also the ancient Tamil poetics she drew from demand much reader involvement and interpretation. Given this, we thought we should be exploratory in our translation approach. So for several of Andal’s verses you will see Ravi’s translation as well as mine.”

For her versions of the translations, Priya adds: “My translations are inspired by Sangam poetics so I offer three translations. The literal is what Andal says; then a parallel meaning, which is my interpretation as a poet that the reader has to interpret. And an inset meaning, which is metonymic and intuitive, where the reader has to extract the meaning as well; this last version opens up doors and takes the reader into her art, divinity and sexuality.

For instance, when Andal is talking of dark rain clouds, the literal translation would be ‘Dense dark clouds of deep monsoon/You hover over the fertile sparkling hills/Of the lord’s dwelling./Breathlessly I chant/His clanging names of victory/Hoping to give fright to my heart’s agony./Ask him to come down to console me/Or must I wait endlessly like/The wilting erukku leaf?’

The parallel meaning is ‘Sombre your spread in the eight directions./Under your gloom I sing his names that flash/glory gained by killing demons. Yet/you pour unafraid of my hailing Tirumal./As rain sews earth and sky in jewel chains/my need for him strings upwards from my wet/body./Am I to be an aromatic desert leaf/that dies in the fertile season?/Ask him this, go.’

And the inset meaning is ‘dark wetness/surrounds/me/time for love making again/again again again/my body yields/its waiting earth/in the dry season of longing accept me.’”

Bringing forth the metonymic and metaphoric nature of Andal’s work enhances the reader’s experience who, Priya believes, is also a participant in the enterprise. “I don’t believe in the passive reader. The reader should be by my side to complete the work, interpret it and make it her own.”

III

P

oet Arundhati Subramaniam describes the “profusion of Andals” in these pages as “a figure that segues between mystic and metaphor, woman and deity”.

Andal’s two works are included by theologian Nathamuni in his seminal Tamil Srivaishnava oeuvre Nalayiram Divya Prabandham and she is given the status as the only woman Alwar saint. And yet she doesn’t come down to us without a fair bit of controversy.

Over the years some scholars have put forth that she is a creation of her father Periyalvar’s imagination. Their rationale is that he adopted Andal as a persona and pen-name, since wearing the mask of a young woman would be the best way to fully express an all-consuming love.

The translators’ foreword in the book states, “Periyalvar adopts a female persona in his numerous pillaitamil compositions, a genre of poetry that he invented, by taking on the role of Krishna’s mother who delights in the child god’s antics.” And anyway, state the sceptics, how could a young girl still in her teens be so knowledgeable about a god and write with such a gifted imagination.

In her defense, the translators assert in their preface that works by Periyalvar are much simpler constructions than Andal’s. Asked whether Andal is her father’s poetic creation, Priya emphatically denies it, “I don’t believe it at all. Most women don’t. This is a response by patriarchal scholars who don’t want to admit that a woman has agency over her sexuality or intelligence or abundant spirituality.”

Priya says that she had been working on and off with these translations for over eight years. Her research led her to consult with various scholars, took her to several of Andal’ s temples and even sent her off the beaten track — “She is constantly invoking nature. When I went to Srivilliputur where she grew up, it was noisy, I couldn’t hear her. So I drove off to the nearest forest – the Meghamalai Wildlife Sanctuary. It was in this quiet space, with its occasional trumpeting elephants, that I could imagine her, go to her time. That’s when I felt close to her.”

After inhaling the fragrances of Andal for such a long time, Priya says she couldn’t help but be transformed. “I was shaken to the core with her sense of the sacred, her superb poetics, her intensity of craving for the divine. When you translate her, that craving becomes your own.”

Excerpts from Andal: Autobiography of a Goddess

Awaken! Auspiciousness floods. Remembering

their calves, cows stream milk. At your door we waitour hair running dew, milk slush around ankles, drenched

in love, for His home is yours too. The world startlesrecalling His compassion in beheading the ten-

headed demon. Rise from petrifaction; you are one of us.(Tiruppavai, translation by Priya, p 11)

Rub the kohl from my eyes, scour the flower-scent

from my body, show me as I am to him, an elemental

offering not good, not bad, but simply present.

Show him as he is to me.In flooded fields of red paddy, carp leap into flight

that doesn’t last, yet won’t subside, and spotted

beetles graze our eyelashes as we splash our song

heavenward for liberation.(Tiruppavai, translation by Ravi, p 19)

In January hoarfrost, I sweep the ground

to draw sacred mandalas with fine sand,intricate adornment of stars and matrices

of dots in rice powder that will dispersein the afternoon void. The art of engaging

beauty for its own form and transient sake.(Nacciyar Tirumoli, ‘The Song to Kamadeva, God of Love’, translation by Ravi, p 29)

As on an indigo lake a shimmering swan tips

nectar from the fluttering purple petals of night lot uses

you drink from midnight hued Vasudeva’s wine

lips. All joy is yours, King of Conches. Once full

you loll in his lotus palm – blank as an eye in inebriated

slumber – while his eyes twitch open like bloodrubies.

All splendour is yours as you possess

his lips that should possess mine. Great is your glory!(NacciyarTirumoli, ‘White Conch from the Fathomless Sea’, translation by Priya, p 89)

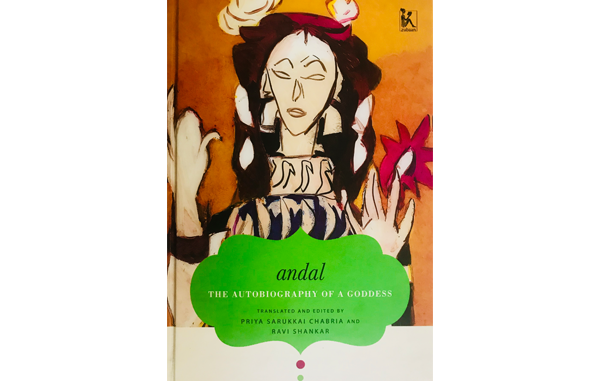

Andal: Autobiography of a Goddess, translated by Priya Sarukkai Chabria and Ravi Shankar. Zubaan Books, Rs 595/$ 21Priya and Ravi receiving the Muse India Translation Award during the Hyderabad Literary Festival in January 2018.

Leave a Reply