K.P. Shankaran

A

rtists and craftspeople are so different that it may not be appropriate to describe Praxiteles, Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo as artists. Art objects are products of inspired imagination and not just the result of skills however great they may be. Of course, there were skilled people in all civilizations and some of their work might surprise us as they did their contemporaries.

Michelangelo was a superbly competent craftsman, but did he produce anything worth describing as a product of inspired imagination? Back from a recent visit to Italy and Greece and after seeing first-hand some of Michelangelo’s best known works, I have reasons to doubt his genius as an‘artist.’ Let me illustrate my point with three works of his, which have been universally acclaimed as great works of art.

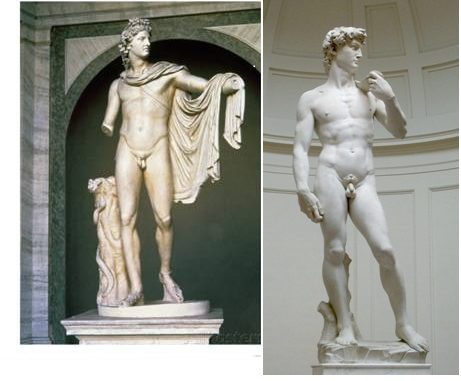

David is a statue of a good-looking youth and Michelangelo’s skill as an artisan sculptor is not in doubt at all. But not an iota of imagination went into the making of this object. It is, in reality, a very well executed variant of Apollo Belvedere (beautiful to look at). The Roman craftsman who copied the Greek bronze original was also an extremely skilled worker on marble. Apollo Belvedere’s muscularity is not as robust as Michelangelo’s David’s. Given the Greek desire to imitate nature, (a practice that Plato condemned) this lack of robustness in Apollo Belvedere could be the result of a less than perfect understanding of human physiology.

Not so Michelangelo; his times and culture had benefited hugely from the medical knowledge, and sciencethat spread throughout medieval Europe from Islamic culture then flowering in Andalusia, Sicily and the Levant. This improved understanding of human physiology would have helped him craft a more robust and physiologically more accurate imitation of nature, which he named David instead of Apollo. David is not only more muscular it is also proportionately bigger. I suspect that because Apollo Belvedere happens to be less muscular in comparison with David, ancient and medieval Indian/Chinese craftspeople would have found it more in agreement with their sense of perfection and beauty.

‘Pretty’ Pieta

M

ichelangelo drew many versions of Pieta: the picture of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of Christ on her lap or in her arms. Many Pietas were made before and after Michelangelo’s famous representation. Michelangelo himself made two other versions, besides the one housed in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. This one is the object of awe and veneration for many visitors. The problem with this Pieta is not that it is badly crafted but it is crafted too well to be a worthy representation of Christ’s suffering. If “art” is as Tolstoy defined it, ‘an activity by means of which one man, having experienced a feeling, intentionally transmits into others’ then Michelangelo’s work is not a religious one but, as Tolstoy saw it, it is an irreligious one.

Many people may not agree with Tolstoy. But it is a fact that Michelangelo’s Vatican Pieta is a very competently crafted ‘pretty object’. But the production of such an object is certainly an indication of the thoughtlessness that coexisted with great craftsmanship. The figure immediately facing the beholder is Mary, the mother of Christ. This well-crafted figure is depicted as much younger than the dead son lying on her lap. This I suppose is an indication that Michelangelo and his fellow craftspeople were content with producing the “commissioned” production to suit the sensibilities of their patron. They made no attempt to educate/shape the sensibilities of either their patrons or of the society they belonged to.

This indeed is a universal tendency of all craftspeople and it is this that helps us differentiate art objects from well-executed craft items.

I have another good reason to believe this hypothesis. Two of Michelangelo’s later works, which were fortunately left unfinished, bear testimony to his incredible genius. Had he completed them he would have most likely converted them into two other pretty pieces of craftwork. One is in the new Opera del Museum, in Florence and the other is Rondanini Pieta in Milan.

Both of these are totality different from the pretty Vatican Pieta. For one thing they are not just well crafted entities. Their beings are saturated with pulsating suffering: suffering that almost envelops them. They are not ‘beautiful’ in the literal sense.Beauty is not the adjective one can use to describe them. The one in Florence is extremely complex. Instead of the two figures that are seen in all garden variety Pietas of his time, this one has three figures trying to hold at bay the unusually heavy downward thrust of the central figure- the dead body of Christ. The arch formed by the heads of Mary, Magdalene and the dead Christ enhances the appearance of heaviness that pulls the figure down, which is very delicately balanced by the bent right leg which touches the ground and the triangle formed by the head and the shoulders of the standing figure. The shape formed by the hands of Magdalene, Mary and Christ, as well as the right leg of Christ, which seems to slip through them catch one’s attention immediately.

This sculpture is an aberration like the one in Milan. At the end of his life the great craftsman Michelangelo, when he worked for himself, seemed to have really strayed, unintentionally though, into the world of artists.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling

A well-informed, non-European first-time visitor who has been fed with ideas of the great artistic merits of the decorations on the chapel ceiling, might well be taken aback by the lack of craftsmanship of these paintings. The chapel is decorated of course, but what is so great about those decorations? Had the ceiling been painted by Raphael or Botticelli how much better it would have looked? Michelangelo, as it would have been visible to anybody of his time, did a very bad job but all his contemporaries praised him. Vasari thought it was the greatest fresco ever made. Raphael imitated him. How can one suspect the judgments of his fellow craftsmen like Vasari, Raphael and Leonardo?

Even though the Romanesque churches beginning in 12thCE, contain ceiling frescos they are not comparable with one produced by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo’s ceiling frescos were entirely a new genre. Perhaps he was the first to experiment with the ‘grotesque’. The word ‘grotesque’ derived originally from the Italian ‘grottesco’ which literally means ‘of a cave’. But 18thCE onwards it is used as the synonym of mysteries, fantastic, unpleasant, disgusting etc.

Michelangelo’s carry both the meanings of the word ‘grotesque’; some of the figures are really grotesque. In the scene of damned people there are ‘grotesque’ figures’. In one place a man’s private part is in a serpent’s mouth. What is more interesting is Michelangelo’s also grotesque in the first sense. Its style was literally taken from a cave.

Domes Aurea

M

bout the year 1480, a Roman boy accidently fell into a hole while he was loitering around the Esquiline hill of central Rome and found himself in a cave with painted pictures. This was the beginning of the artistic genre called “ grotesque”. How much of this discovery helped Michelangelo and his fellow crafts persons is an open question. The hole into which the boy fell, in fact was part of the great palace “Domes Aurea” built by Emperor Nero in 64-68CE.

It is now a well-known fact that Michelangelo, Raphael etal climbed down to copy those frescos which were still then glowing on the walls and ceilings, all intact, because of its subterranean existence for more than a thousand years. According to the art historian Hetty Joyce (Grasping at Shadows) there is reason to believe that Michelangelo, Raphael etal vandalized these after copying them in order to conceal the source of their technique and style. European historians till recently suppressed many of these facts and tried to present the so-called ‘renaissance art” as the product of local genius.

When we return to Michelangelo’s Sistine frescos, what we see there is, stylistically speaking, the resurfacing of a forgotten tradition. Michelangelo’s fellow craftspeople eulogized him for this appropriation of a Roman style for the purpose of presentation of Biblical mythology. To my mind, this deliberate attempt to attribute extraordinary creative abilities to Michelangelo, which the subsequent European tradition helped to carry forward, was intended to underplay or even perhaps gloss over the influence that the Roman tradition had on him and also his total appropriation of Roman designs.

In fact those Roman designs are the ones that filled almost all the frescos of renaissance buildings. They also contributed to the reemergence of linear perspective which has also been regarded as a discovery made by painters in the 15th century. The design of the Sistine ceiling frescos is for instance, from Nero’s painter Fabulus. Michelangelo only incorporated ‘content’ into the Fabulusian form and in executing which he has certainly left a lot to be desired.

In my view, most of Michelangelo’s finished works lacked originality and therefore despite being an outstanding craftsman sculptor, he was not deserving of the title of a ‘great artist’ that the world had so generously bestowed on him.

K.P. Shankaran was Associate Professor at St. Stephen’s College New Delhi, where he taught Philosophy He also taught Political Philosophy and Gandhian Thought at Delhi University. He has written a book, “Marx and Freud on Religion” and many essays on Gandhi. He is currently working on a book about Brancusi, a Romania-born French sculptor.

Leave a Reply