Mithi Mukherjee

I

Locating “Difference” in Discourse of freedom.

I

n the past two decades, subaltern historians and postcolonial scholars have brought to our attention the need to question the generally assumed universality of Western categories in framing the histories of the rest of the world.1 The exclusive deployment of Western concepts to explain historical development in India and other non-Western countries, they say, not only has marginalized indigenous systems of knowledge and practices, but has also resulted in the histories of these countries being presented in negative terms as a deviation from the universal trajectories of capital, democracy, and liberalism, which are themselves grounded in particular historical experiences of the West. Thus, as Dipesh Chakrabarty, among others, has argued, most scholars trained in this intellectual tradition have characterized India as “not modern” or “not bourgeois” or “not liberal.” The new intellectual sensitivity toward non-Western systems of thought has resulted in a significant number of works that deploy the critical category of difference.

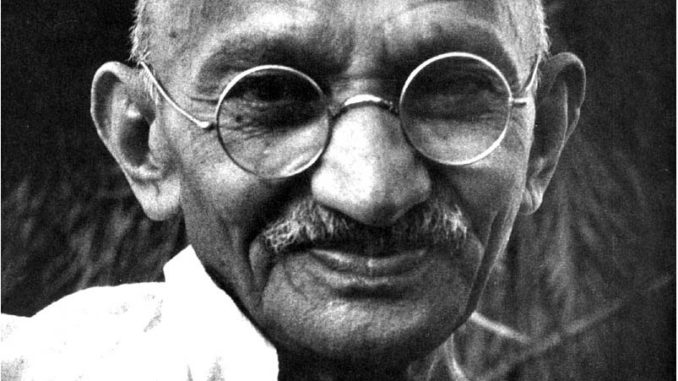

Yet none of the four major schools of historiography on modern India—Marxist, Cambridge, nationalist, and subaltern—has extended this notion of difference to the discourse of freedom associated with the Gandhian nonviolent resistance movement against British colonialism. This is a surprising omission, given the striking ways in which the Gandhian discourse of freedom departed from the Western discourse of freedom. While the distinctiveness of the Gandhian movement in relation to other forms of anticolonial resistance of the day was evident to Gandhi’s contemporariesand has been noted by scholars, the use of difference as an analytical category to distinguish the specificity of his political discourse has not been central to Gandhian studies.2

One possible explanation for this lack of attention is that historians of modern India do not see the notion of difference as extending to the exteriority and autonomy of the intellectual and cultural traditions that are reflected in Gandhi.3 Whereas the Western discourse of political freedom, based on the concepts of individual rights, private property, representative government, national identity, and the nation-state, has generally been assumed to be a universal framework without which neither freedom movements nor democracies in other parts of the world could succeed, the Gandhian movement of nonviolent resistance against British colonialism had its own discourse of freedom, grounded in a different tradition of thought and practice.4 It was anchored not in the Western notion of freedom, but rather in the Indic—Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain—discourses of renunciative freedom (moksha and nirvana in Sanskrit) and their respective ascetic practices.5

Thus the significance of an inquiry into the nature and origins of the Gandhian concept of freedom extends much farther than the historical moment it seeks to understand. Because so much of the critical discourse in the social sciences and the humanities today is at least implicitly anchored in the dominant Western notion of freedom, it has been difficult to gain a critical distance from it. An exploration into the history of the Gandhian movement can open up a position of exteriority on this Western discourse, showing that it is not self-evident. By bringing the two traditions under each other’s critical gaze, we can, at least potentially, think in new ways about freedom in the modern world, ways that can take us far beyond the limits and specificities of South Asian history or scholarship.6

The question of difference as it relates to the nature and implications of the historical encounter between Indic and Western cultural and intellectual traditions under the British Empire can be broadly approached in two ways: difference as identity and difference as thought. In the discourse of difference as identity, the notion of difference functions as the basis of cultural and national identity. In the discourse of difference as thought, on the other hand, difference functions as a marker of the nature and specificity of thought, its origin and historical significance. The crucial difference between the two approaches is that difference as thought goes beyond identity in its claim to universality and truth.

If there has been no serious attempt in modern Indian historiography to situate the Gandhian movement in terms of difference, it is largely because scholars have understood difference primarily as the ground for a discourse of national and civilizational identity, not as a source of categories. There is an underlying assumption that non-Western intellectual traditions do not offer categories of thought with claims to truth—that they become historically significant only as emblems of identity. Not surprisingly, therefore, one of the most frequently cited political arguments advanced by Marxist and left scholars in India against deploying the notion of difference has been that any critique of Enlightenment rationalism of the West based on Indic traditions risks promoting nativistic indigenism, which in turn feeds into the rising tide of Hindu nationalism. The presumption—unstated though it may be—is that the only possible role for Indic traditions in history today is as symbols of identity, not as sources of thought. Such apprehension is ironic, in that the Gandhian movement was in fact one of the first mass political movements for national independence to be based on the rejection of identity and nationalism.

There is, however, a far more important methodological reason for the absence of works that problematize Gandhian discourse in terms of difference. In the form of Marxism that is dominant in Indian historiography, discourse is nothing more than a reflection of class interest and class conflict, the true and a priori driving forces of history. Marxist historians, therefore, have completely ignored the historical specificity of Gandhian discourse and its difference from Western discourse, seeing Gandhi’s ethical practices as nothing more than a cover for what were in essence shrewd bourgeois political tactics, and therefore an aspect of his politics that need not be taken seriously. While the Cambridge and nationalist schools have important differences, they share the Marxists’ dismissal of discourse as constitutive of history. Not surprisingly, for example, Cambridge historians have dissociated the specific tactic of nonviolence from the discourse on which it was grounded to suggest that the latter was nothing more than a clever political tool used to achieve various external ends in the form of social, national, and class interests.7 The assumption behind much of this historiography is that Gandhian discourse was not anchored in an end of its own.

The case of the subaltern school is somewhat more complex. Insofar as most subaltern historians have based their own reading of Gandhi on Marxist categories, they too have neglected to focus on the specificity of Gandhian discourse.8 In their more general historical explorations into modern India, however, particularly in the last two decades, they have focused on discourse and also deployed the notion of difference. Partha Chatterjee, one of the most influential subaltern historians of modern India, uses the concept of difference in his seminal work on Indian nationalism only as it relates to the origin of the discourse of national identity.9 For him, difference as a marker of the divide between India and the West becomes important for nationalist discourse at the “moment of departure” or origin, as it sought to make the civilizational difference of India the foundation of national identity. Significantly, however, Chatterjee does not problematize the Gandhian movement in terms of the same notion of difference, and he points to Gandhi’s distinctiveness only in relation to other Indian nationalists. Beyond noting in passing some characteristic features of the movement as reflective of “peasant consciousness,” he makes no serious attempt to problematize Gandhian discourse in its precise nature and origins.10 In his view, the real historical significance of the Gandhian movement lay in its use by the Indian bourgeoisie as a tactic to mobilize the peasantry against the British Empire even as it denied them any share in the postcolonial state.11 Chatterjee reduces discourses in his analysis to two kinds of identity—class and nation— and so feels no need to problematize discourse as thought. For him, the distinctiveness of Gandhian discourse can ultimately be said to be a distinction without significance, having no historical meaning other than as a tool in the rise of the Indian bourgeoisie.

The question of difference has been central in the works of another leading subaltern scholar, Dipesh Chakrabarty.12 In Provincializing Europe, Chakrabarty uses difference in the sense of excess, contending that modernity in India is too complex and specific to fit into the framework of thought inherited from the West.13 By “provincializing Europe,” he aims to expose the limits of the Western intellectual traditions’ claims to totality from the margins of colonial and postcolonial history. His own framework, however, does not adequately problematize the nature and implications of the encounter between Indian and Western thought in terms of difference. After all, his notion of difference as excess is also applicable to the West, as no Western system of thought could conceptualize life even in the West in all its complexity and totality. Also, even as Chakrabarty assumes that the West continues to be the sole source of thought with claims to universality and truth, and as such is not entirely bound by geography or history, he finds India to be lacking any claim to thought, a claim that would require the ability to rise above the particularities and idiosyncrasies of place. Ultimately, Chakrabarty does not see the possibility of an exteriority to the Western intellectual tradition in the sense of a competing system of thought that originates outside the West. It is not surprising, therefore, that what began as a claim to provincialize Europe ends up as not much more than an exploration into how Western thought “may be renewed from and for the margins,” that is, the non-West.14

Notwithstanding Chakrabarty’s and Chatterjee’s works, a position of exteriority to Western intellectual and political traditions that departs from the postcolonial and subaltern understanding not only is theoretically possible but has in fact played a significant, even central, role in India’s movement for independence.15 Gandhi himself was aware that Indian intellectual traditions were widely assumed to be a spent force as a source of thought and could serve as nothing more than markers of identity. “Of all superstitions that affect India,” he wrote in 1921, “none is so great as that a knowledge of the English language is necessary for imbibing ideas of liberty, and developing accuracy of thought.”16 What he called the greatest of all “superstitions” has also emerged as the most important and enduring intellectual legacy of colonialism in India: the belief that because the West is the sole source of categories in the modern world, English is the sole language of thought as such in India. It is against this “superstition” that we need to situate not only the genealogy of Gandhi’s own reflections on the category of liberty, but also the nonviolent anticolonial movement that he led. If the question of the autonomy of Indian languages and their ability to develop categories of thought arose for Gandhi in the context of a discussion of the concept of liberty, it was precisely because this concept as articulated in all its difference and specificity in Indian languages had been the guiding principle of his own intellectual and political exertions.

The historiographical approaches have all attempted to trace the origins of the discourse and practice of nonviolent resistance to Gandhi as a person. Even historians who focus on Gandhian ideas have tended to see them as deriving either from his personal reading of Western writers such as Tolstoy, Ruskin, and Thoreau or from his upbringing.17 They are working from the assumption that the pre-given subject stands above history while determining its movement, thus forgetting that the subject itself is a historical construction and is shaped by larger historical forces. There is a different way to look at the historical figure of Gandhi, however, through the use of the methodological category of the enunciative persona (not person). From this standpoint we can see him as the samnyasin, or renouncer, in the role of a political activist and the leader of a resistance movement. It is because Gandhi donned the enunciative persona of a samnyasin that the Indic tradition of renunciative freedom became the basis for a new kind of politics—a politics of nonviolence.

The category of enunciative persona makes it possible to approach discourses in terms of larger historical, institutional, and cultural genealogies rather than simply attribute them to substantive subjects, whether individuals, social groups, or identities. It also enables us to bring discourse and practices together in a complex interrelationship and moves us away from studying politics as simply a history of ideas or thoughts.18 From this methodological perspective, Gandhi the person is only the bearer of a principal enunciative persona, the real subject of the discourse: the renouncer. The notion of the enunciative persona, in short, refers to the historically constructed subject in opposition to the often unproblematized assumption of an ahistorical notion of the person as the subject of history.19

Gandhi was trained as a lawyer, and his early political activism against the racial policies of the British colonial government in South Africa (1894–1914) was lodged within what we might call a juridical discursive paradigm, where the primary object was to appeal to imperial justice against the unjust acts of the local government by organizing petitions to Parliament for the redress of grievances.20 This juridical discourse, like the insistence on nonviolence that logically followed from the faith in imperial justice, was not unique to Gandhi; it was also the basis for the anticolonial agitation in India during the same period. It is intriguing, however, that even as Gandhi’s actions in South Africa were framed by juridical discourse, there was a simultaneous irruption in his life of a set of ethical, spiritual, and ascetic practices that were not accompanied by a discourse that could make them intelligible in relation to the political challenges of the day.21 Tolstoy Farm, where Gandhi settled with his family and some close friends and followers and began what would become a lifelong experiment with practices such as fasting, celibacy, meditation, and manual labor, reflected his deliberate decision to withdraw from and even renounce modern city life.22 As a response to what was obviously a political challenge faced by a colonized people, his retreat to a rural ascetic and ethical lifestyle seems a curious move indeed.

This response, however, was not entirely unique or unprecedented. With the advent of colonialism in late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century India, issues of subordination, inequality, and freedom for the colonized had become critical for Indian thinkers even before Gandhi. Strikingly, these thinkers often, if not invariably, responded in precisely the same conflicted, dualistic way. Why? Why did the search for freedom invariably take an ethical, ascetic, and spiritual turn, while the relationship between the people and the government continued to be articulated in terms of justice rather than political freedom? The answer lies in the fact that even as much of anticolonial discourse was grounded in the idea of imperial justice, it also came to be anchored—as if by reflex—in the Indic traditions of ascetic renunciative freedom. While the categories and goals of freedom and liberty had come to be a part of political discourse and practice in the West, in precolonial India they had been a part of spiritual and religious discourse and practice.23

By the nineteenth century, what has been recognized as a distinctly Western discourse of political freedom as self-government had generally come to be based on two interrelated forms of identity: individual identity, as reflected in the notions of individual rights and private property, and collective identity, as reflected in the notions of popular national sovereignty, the nation-state, and the ideology of nationalism.24 In India, by contrast, the category of freedom was common to all the major Indic religions, including Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. Contrary to the popular perception that Hinduism is a religion of personal gods, it in fact has a strong parallel tradition in which there is no conception of God at all. In this tradition of Hinduism, moksha, or liberty, is the ultimate of all human goals, and to attain moksha is to lose one’s identity, individuality, and specificity.25 In other words, in their relationship to identity, the Indic and Western discourses of freedom were diametrically opposed. Whereas the Western understanding of freedom was based on national and individual identity, the Indic understanding meant losing any and all forms of identity. Given that the world operates within a web of identities, the logical conclusion of the Indic understanding of freedom as moksha was a complete renunciation of the world. Thus the Western and Indic discourses of freedom can be characterized as identitarian and renunciative, respectively.

In premodern Indian society, life was conceptually organized around the pursuit of four goals, known in Sanskrit as Purusharthas, or ultimate human goals: dharma, the pursuit of the good, constituting the domain of ethics and law; artha, the pursuit of power, constituting the domain of politics; kama, the pursuit of pleasure, constituting the domain of sexuality; and moksha, the pursuit of freedom, constituting the domain of renunciative, ascetic, and meditative practices. Each of these domains had its own textual and discursive tradition, the dharmasastra, the arthasastra, the kamasutra, and the mokshasastra, belonging to various religious schools and sects pertaining to ascetic and meditative practices, respectively.26 However, a hierarchy was assumed in terms of the relative importance of each of the four goals, with the pursuit of moksha ranked the highest and of kama the lowest.

Within this framework, freedom and politics as the pursuit of power constituted two exclusive and mutually incompatible domains. Whereas the latter involved governance and warfare, the former required complete renunciation of the other three goals, including power. Given this perspective, it is not surprising that Gandhi’s involvement in the twentieth-century anticolonial resistance movement was marked by a commitment to renunciative freedom as the highest goal, and at the same time by a critique of the Western discourse of freedom as being partly an exercise of power, most evident in colonialism. It was as part of this philosophical tradition that the samnyasin, or renouncer, as the seeker of moksha, or renunciative freedom, came to be one of the principal figures in Indian life.27

II

An Indic discourse of Freedom: Renunciation

I

t was the advent of British colonial rule in India and the challenge posed by the introduction of the Western discourse of freedom that brought renunciative freedom into the center of Indian thought. As a parallel indigenous discourse of freedom, moksha had a certain sense of kinship with, but more significantly a strong sense of rivalry with, the Western notion of political identitarian freedom.28 It was inevitable that the two traditions would clash. This historic encounter presented Indian thinkers with a fundamental dilemma: Were they to abandon the received understanding of renunciative freedom and accept the Western discourse of political freedom, or were they to attempt to build a bridge between the two? Was such a bridge even possible, or were the two discursive traditions incompatible? This conflict and the need to resolve the tension created by the contrary pulls of the two discourses emerged as the primary dilemma for Indian political thinkers in the colonial period.

There were three options available to Indians at this juncture of colonialism. They could ignore the colonial political system and continue with the pursuit of renunciative freedom. They could adopt the Western notion of political freedom and abandon a significant part of their religious and spiritual traditions, while endeavoring to lay the foundations of a political discourse of resistance against the British colonial government in India. Or they could try to find some middle ground between the two traditions of freedom without abandoning either entirely.

It was this third option that nineteenth-century Indian thinkers such as Rammohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, and Rabindranath Tagore chose, by creating a discourse of ethical freedom as a bridge between the imperative of renunciative freedom and political freedom. The established discourse of freedom underwent two fundamental transformations in modern India. In the first half of the nineteenth century, as a result of the encounter with the Western discourse of freedom brought by British colonialism, the pursuit of renunciative freedom, which in the past had been an individual pursuit and involved a complete renunciation of the world and an ascetic retreat from it, was transformed into an ethical engagement with the world in the form of social service or service to humanity as a whole. In 1920, with Gandhi’s declaration of the non-cooperation movement against British rule, this pursuit of renunciative freedom through ethical engagement with the world was transformed yet again, this time into a political engagement with the world involving active confrontation and conflict with the established political system. The Gandhian revolution in the discourse of renunciative freedom consisted in a novel combination of an ethics of service to society and an ethics of resistance to the state.

Unlike renunciative freedom, which required a complete withdrawal from the world, ethical freedom allowed one to engage with the world without losing the telos of freedom. The way to do this was to let go of one’s individual identity and interests by dedicating oneself to the service of society and the greater good. This ethical turn allowed Indian thinkers in the nineteenth century to avoid direct political confrontation with the colonial government, whose role they continued to articulate in terms of the discourse of imperial justice.29

It was Rammohan Roy who brought the discourse of renunciative freedom to center stage in Indian thought by deliberately abandoning bhakti as the dominant form of Hinduism and founding a new religion in 1830 called Brahmo Samaj, based on the ancient Upanishadic ideas of Brahman and moksha.30 Marking a break from the past, however, Roy argued that the pursuit of moksha did not require one to renounce the world. Rather, it could now be achieved by devoting oneself to social service.31 It is important to note that this ethical compromise stopped far short of involvement with the affairs of state.

The split between juridico-political liberty and the discourse of renunciative freedom is also evident in the late-nineteenth-century writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterji, one of the most important literary and intellectual figures in modern Bengal and India. Chatterji argued in numerous essays that the juridical discourse of liberty, which presupposed the individual as the subject of law, with rights given or not given by institutions of political society, was a Western import.32 The real telos of Indian life as handed down by the ancient civilization of India was not political liberty, defined as the instrumental use of freedom for the pursuit of material ends, but freedom from desire, or mukti/moksha, which was an end in itself.33 Significantly, he viewed moksha, the pursuit of renunciative freedom, as indistinguishable from what he called dharma, defined as ethical conduct in the service of humanity. In Chatterji’s view, politics was not the domain in which freedom could be exercised or realized; at most it could help to create the conditions under which one had the choice to pursue real freedom, which was moksha. Thus it is not surprising that he never fully opposed British rule in India.34 Within his discourse, there was no need for opposition or resistance to foreign rule because politics itself was foreign to the attainment of moksha. The goal of national independence under which people could exercise their freedom as legislators by making laws for themselves fell outside his concerns.

It was Swami Vivekananda, however, who had the most lucid insight into the nature of the challenge facing the Indic tradition of renunciative freedom with the establishment of the British Empire and contact with Western intellectual and political traditions. Vivekananda precisely articulated the distinction between the West and India as not just a divergence between Indian spirituality and Western materialism—a generalization that was common in the writings of that period—but a fundamental difference between their respective notions of freedom. In a lecture titled “Hindu and Greek,” he stated:

The Greek sought political liberty. The Hindu has always sought spiritual liberty. Both are one-sided. The Indian cares not enough for national protection or patriotism, he will defend only his religion; while with the Greek and in Europe (where the Greek civilization finds its continuation) the country comes first. To care only for spiritual liberty and not for social liberty is a defect, but the opposite is a still greater defect. Liberty of both soul and body is to be striven for.35

Vivekananda’s writings evince the urgent need to somehow build a bridge between the two notions of freedom, to establish some middle ground between them. LikeBankim Chandra Chatterji and Roy, he found this path in a discourse of ethical freedom.

Redefining true renunciation as unselfish work and work without the desire for results, Vivekananda stated:

the ordinary Samnyasin gives up the world, goes out and thinks of God. The real Samnyasin lives in the world, but is not of it. Those who deny themselves, live in the forest and chew the cud of unsatisfied desires are not true renouncers. Live in the midst of the battle of life . . . Stand in the whirl and madness of action and reach the Center.36

The goal for the real samnyasin, then, was ethical service to humanity:

The true samnyasins forgo even their own liberation and live simply for doing good to the world . . . The Samnyasin is born into the world to lay down his life for others, to stop the bitter cries of men, to wipe the tears of the widow, to bring peace to the soul of the bereaved mother, to equip the ignorant masses for the struggle for existence . . . and to arouse the sleeping lion of Brahman in all by throwing in the light of knowledge.37

Vivekananda exhorted his disciples to immerse themselves as samnyasins in the work of educating the masses, particularly women, and in charitable activities to reduce poverty and illiteracy.38 Indeed, he was inspired by the goal of ethical freedom to establish the Ramakrishna Mission, a network of charitable institutions run by samnyasins whose primary aim was the service of humanity.39 As with Roy, Vivekananda’s attempt to find some middle ground between the two notions of freedom stopped far short of anything that could be recognized as political.

The most vivid illustration of the nature of this ethical pursuit of moksha and the historical-political circumstances under which it was invented can be found in Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Gora (White Boy).40 Tagore, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, was second only to Gandhi in his intellectual importance and his influence on modern Indian culture.41 The title character in Gora is an extremely conservative Brahmin Hindu who is leading a Hindu nationalist movement against British colonial rule, a movement that is also hostile to Muslims. At the height of his political career, he learns that the Brahmin Hindu couple who raised him were not his real parents; he is, in fact, Irish by birth: he was left in the care of his Hindu family by a couple from Ireland after the Rebellion of 1857 against British rule.42 Gora is devastated by this revelation, for now it is impossible for him to continue to lead an independence movement based on Hindu religious and national identity.

He suddenly finds himself to be neither a Brahmin nor a Hindu, nor indeed even an Indian. At the same time, he has lived the life of a Hindu for far too long to find his way back to his Irish and Christian identity. It is as if an abyss has opened up right under his feet.

But it is through this complete loss of identity that Gora goes on to discover his true purpose: selfless service to India and to all of humanity. In Tagore’s eyes, this is the moment of his real freedom. With this discovery, however, the novel ends, implying that with the attainment of Gora’s true freedom, the political project of national independence from British rule has been abandoned. In effect, Tagore, like his predecessors, failed to reconcile the pursuit of moksha as ethical engagement with the world with a discourse of anticolonial resistance.43

At an obvious level, Gora reflects Tagore’s concern about a new form of nationalism based on Hindu national identity that was emerging in India in the early twentieth century. However, given that this form of Hindu nationalism was essentially derivative of the modern discourse of political freedom, with its three pillars of national identity, nationalism, and the nation-state, the novel is at a deeper level a critique of the discourse of political identitarian freedom as such. If the question of identity is central to the story, that is because Tagore viewed the modern discourse of political freedom as based on a fundamental division between the self and the other, a division that was at the root of much of the conflict that accompanied the rise of nationalism in the modern world. In the discourse of ethical freedom, defined as service to society or humanity as a whole, any kind of identity, individual or collective, not only signified the absence of freedom but was, in fact, a positive form of bondage.44 From the perspective of the Indic understanding of freedom, the modern notion of political freedom was a contradiction in terms.

III

Imperial Justice as Divide and Rule.

J

ust as the discourse of freedom in India seemed unable to get past the ethics of social service in the pre-Gandhian period, political discourse was equally moribund—trapped in a discourse of imperial justice, it had been unable to find its way out toward national independence.45 Imperial justice was the larger discursive formation within which the British policy of divide and rule operated in the post-1857 period. The Rebellion of 1857 had dramatically exposed the fragility of the East India Company’s rule over India.46 It had also driven home the fact that significant parts of the Indian population were capable of uniting when it came to opposing the colonial government, and that force alone would not suffice to maintain the British Empire in India.

It is significant, therefore, that the Queen’s Proclamation of 1858, which put the British monarchy at the helm of the British Empire in India under the discourse of imperial justice, went hand in hand with a discourse that denied India the status of a nation and portrayed it as a divided society at war with itself.47 Torn by internal conflict, India was in desperate need, it was claimed, of a neutral and therefore preferably foreign power to govern it and secure the peace. The colonial hope was that the fragmentation of Indian society into innumerable minorities would keep it trapped in the discourse of imperial justice with no access to the discourse of political freedom, making the British presence seem permanently indispensable. It was this brilliant invention of the discourse of imperial justice that turned the exteriority, or foreign origin, of the colonial state into a strength rather than a weakness; the exteriority of the state to the “native” society was presented as a requirement not just for the peace and security of the country, but for its very existence.

Even Gandhi himself, until as late as 1918, framed his political discourse in terms of the goal of imperial justice. After his return to India from South Africa in 1914, even while leading some of the most extensive peasants’ and workers’ movements in Champaran, Kheda, and Ahmedabad, he continued to view these movements primarily in terms of the imperial juridical paradigm, as essentially pleas for justice.48 With the passage of time, however, the long-held and surprisingly widespread hope of imperial justice was beginning to appear to the people of India more like a political trap intended to keep India a British colony indefinitely.49 Yet, while the inadequacy of the discourse of justice was becoming clear, the Indic discourse of freedom, having abandoned the renunciative path, had come only so far as an ethical engagement with the world. What was urgently required for an adequate response to the challenge of colonialism was a discourse of resistance.

It was under these circumstances that the underlying violence of British colonial rule was brutally brought home to Gandhi with the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in the Punjab in 1919.50 Large numbers of Indians, including old people, women, and children, were slaughtered by the British army at a nonviolent prayer meeting that was taking place within a walled compound, held in response to Gandhi’s call for a nationwide protest against the Rowlatt Act.51 The deliberate nature of the massacre and the brutality with which it was carried out, followed by the British government’s refusal to punish the general who had ordered it, Reginald Dyer, finally shut the window of hope that the discourse of imperial justice had offered to Gandhi and others in the Indian National Congress for more than three decades.52 It was at this moment that Gandhi departed radically from his earlier juridical modes of agitation, such as petitioning, signature campaigns, and presenting memoranda to the British government, and began a new era of open resistance and confrontation. The possibility of any reconciliation between the Indian people and the British government now appeared to him illusory. As he stated during his 1922 trial, the massacre at Jallianwalla Bagh had proved that the colonial government, “established by law in British India,” was being used “for the exploitation of the Indian masses and for prolonging her servitude. I hold it to be a virtue to be disaffected towards a government which in its totality has done more harm to India than any previous system.”53

The beginning of a new discourse of resistance was dotted by major milestones, including the non-cooperation movement in 1920, the civil disobedience movement in 1930, and the “Quit India” movement in 1942.54 Given that Gandhi himself had been a lawyer, this departure from the discourse of imperial justice became dramatically evident in his call to ban practicing lawyers from leading or even participating in the anticolonial movement. Insofar as any association with the British judicial system reflected a residual faith in the discourse of imperial justice, it had to be thoroughly rejected.

Thus the time had come for the creation of a new order of discourse. It is not surprising that after Gandhi’s arrival in India, even as he began to grapple with the questions of the day, he also began to move, largely unawares, toward the figure of the samnyasin. For while renunciation had been the condition for truth in society through much of Indian history, the enunciative persona of the renouncer had been seen as the sole agent of truth. In contrast to scholars of the renunciative tradition, however, Gandhi came to the discourse of moksha in search of an answer to a political question. It was as a political activist that he became a renouncer.

IV

Political Activist as Renouncer

G

andhi made this significant move at a historical juncture when the limits of the discourse of imperial justice stood exposed. Stepping into the enunciative position of the samnyasin enabled him to be an enunciator of truth with the power to challenge the discourse of the British Empire. Vivekananda, who had himself become a samnyasin, had asserted that to speak of politics in India, one had to speak the language of religion.55 And in the view of the masses of India, only the renouncer could speak the true language of religion: when one “preached as a householder,” Vivekananda pointed out, “the Hindu people will turn back and go out. If you have given up the world, however, they say, ‘He is good, he has given up the world.’ ”56 Having detached himself from the affairs of the world and identified himself with the cosmos, the renouncer stood outside society, and it was precisely that position of disinterestedness and impartiality toward the affairs of the world that made him the enunciator of truth. Vivekananda had even suggested that the authority that the samnyasins commanded as enunciators of truth in Indian society be put to the service of politics: “This tremendous power in the hands of the roving samnyasins of India has got to be transformed, and it will raise the masses up.”57 In a sense, then, we can say that the emergence of Gandhi, and the discursive position that he came to occupy, was anticipated in the discursive context of late-nineteenth- and twentiethcentury India, where the discourse of renunciation had come to be tied to the discourse of ethical service to society.58 It was because Gandhi spoke as a samnyasin that his discourse was accepted and recognized as the discourse of truth.

Even while occupying the enunciative position of a samnyasin, Gandhi significantly transformed its meaning. Whereas in its traditional religious sense samnyasa meant the renunciation of all worldly activities, Gandhi redefined the concept:

Samnyasa does not mean the renunciation of all activities; it means only the renunciation of activities prompted by desire and of the fruits of action performed as duty. This is real freedom from activity. That is why one must learn to see inactivity in activity and activity in inactivity.59

In his declaration of non-cooperation with British rule, however, he also marked a break from the nineteenth-century ethical discourse of moksha, the pursuit of freedom as social service. For it was in the Gandhian discourse that the discourse of transcendental freedom, previously grounded on the explicit rejection and exteriorization of politics, came to intersect with the historical concern for independence from British rule and the idea of resistance.

In this age, only political samnyasis can fulfill and adorn the ideal of samnyasa, others will more than likely disgrace the samnyasin’s saffron robe . . . One who aspires to a truly religious life cannot fail to undertake public service as his mission, and we are today so much caught up in the political machine that service of the people is impossible without taking part in politics.60

For Gandhi, however, political engagement had to be subordinated to the idea of renunciative freedom. It was at the core of his revolutionary innovations in the field of political strategy. His insistence on nonviolence derived from his belief that politics should always be subordinated to the idea and practice of renunciation. “For me the effort for attaining swaraj/national political independence is a part of the effort for moksha . . . I would not be tempted to give up my striving after moksha even for the sake of swaraj.”61 The end was not the overcoming of the other through appropriation by the self, but the transcendence of desire itself. Intrinsically tied to the goal of moksha, therefore, was the ideal of nonattachment, anasakti. Attachment led to worldly involvement and was a major obstacle to the attainment of renunciative freedom. The aspirant toward moksha thus had to cultivate a total absence of desire. In Gandhian discourse, the idea of freedom was located outside G. W. F. Hegel’s dialectic of master and slave, for Indians, while refusing to be slaves, would also renounce the desire to be masters. The self was to become a cipher in which truth could reside. “When the sense of ‘I’ has vanished, we cease to feel that we are subject to anyone’s authority. He who feels himself to be a cipher experiences peace in all conditions of life.”62 Freedom, then, was indistinguishable from renunciation—renunciation of desire and of identity.

For the political samnyasi or satyagrahi, certain renunciative practices were imperative. 63 “Self-effacement is moksha,” wrote Gandhi in his autobiography, “and whilst it cannot, by itself, be an observance, there may be other observances necessary for its attainment.” The practices of brahmacharya (celibacy), fasting, aparigraha (non-possession), and especially ahimsa (nonviolence) were essential to the life of a satyagrahi. “Satyagraha,” Gandhi declared at the commencement of the movement around the Rowlatt Act, “is a process of self-purification, and ours is a sacred fight, and it seems to me to be in the fitness of things that it should be commenced with an act of self-purification. Let all the people of India, therefore, suspend their business on that day and observe the day as one of fasting and prayer.”64 It was from this perspective that the discourse and practice of freedom in India came to be tied to the concepts of duty, responsibility, and conscience, rather than to individual rights.

The radical nature of the shift from the peaceful, ethical pursuit of freedom to a confrontational albeit nonviolent politics of resistance is evident in Tagore’s public critique of Gandhi’s politics.65 Gandhi had always insisted that the telos of national independence be subordinated to the attainment of moksha, which for him meant the effacement of the consciousness of the self or the ego. In Tagore’s eyes, Gandhi’s declaration of non-cooperation and the initiation of active resistance were symptomatic of his abandonment of the primacy of the discourse and goal of renunciative freedom over national independence.66

As a thinker who shared Gandhi’s commitment to the ideals of renunciative and ethical freedom, Tagore found the call for non-cooperation to be divisive and provocative. For him, the rejection of everything foreign was exclusivist, and therefore unacceptable. Moksha, as reconstructed in its ethical form, had come to mean identification with all of humanity rather than a retreat into national or communal identity, and Tagore believed that this form of resistance would inevitably lead to disharmony, conflict, and hostility between nations and peoples.67

The idea of noncooperation is political asceticism . . . It has at its back a fierce joy of annihilation which at its best is asceticism, and at its worst is that orgy of frightfulness in which the human nature, losing faith in the basic reality of normal life, finds a disinterested delight in unmeaning devastation, as has been shown in the late War and on other occasions . . . No in its passive moral form is asceticism and in its active moral form is violence. The desert is as much a form of himsa (negligence) as is the raging sea in storm; they both are against life.68

The philosophical thought that underlay Tagore’s criticism of Gandhi’s non-cooperation derived from a commitment to the Upanishadic idea of advaita, or nondualism, which did not allow any division of the world into self and other. This idea, however, preempted any attempt to construct a political discourse of opposition, confrontation, or resistance, which is necessarily articulated in terms of self and other. “The infinite personality of man (as the Upanishads say) can only come from the magnificent harmony of all human races,” Tagore wrote.

My prayer is that India may represent the cooperation of all the peoples of the world. For India, unity is truth, and division evil. Unity is that which embraces and understands everything; consequently it cannot be attained through negation. The present attempt to separate our spirit from that of the Occident is an attempt at national suicide . . . No nation can find its own salvation by breaking away from others. We must all be saved or we must all perish together.69

Gandhi’s response was to assert the importance of rejection in arriving at truth. “Rejection is as much an ideal as the acceptance of a thing. It is as necessary to reject untruth as it is to accept truth . . . we had lost the power of saying ‘no.’ It had become disloyal, almost sacrilegious to say ‘no’ to the government.”70 Referring again to the Upanishads (Brahmavidya), he reminded Tagore that the pursuit of freedom necessarily required a series of rejections, because the ideal of renunciative freedom could not be defined positively and pursued directly. Gandhi pointed out that what he called Tagore’s “horror of everything negative,” including resistance, was not truly representative of the Upanishadic approach to renunciative freedom. The philosophers of the Upanishads had, after all, attempted to define the Brahman—the absolute—not in terms of its positive attributes, which could have been limiting and would have turned it into a finite entity or identity, but rather by rejecting all positive definitions: “the final word of the Upanishads (Brahmavidya),” asserted Gandhi, “is ‘Not.’ Neti was the best description the authors of the Upanishads were able to find for Brahman.”71 This did not mean, however, that non-cooperation was an exclusive doctrine based on identity:

Our non-cooperation is neither with the English nor with the West. Our non-cooperation is with the system that the English have established, with the material civilization and its attendant greed and exploitation of the weak . . . Indian nationalism is not exclusive, nor aggressive, nor destructive. It is health-giving, religious and therefore humanitarian.72

Even while Gandhi cited the Upanishadic principles of negation to defend resistance against the British Empire, he clearly was extending the logic of that negation as it had historically been understood. Negation as renunciation and negation as resistance are two very different kinds of acts. Whereas negation as renunciation involves withdrawing oneself from the world, negation as resistance implies an active engagement with the world in order to change it. The Upanishadic ideal in its traditional form had involved samnyasa, leading to a complete ascetic withdrawal from the world. For such a renouncer, active political non-cooperation would have been unimaginable.

This unprecedented and revolutionary transformation of the renunciative tradition to include direct confrontation with an unacceptable political establishment was necessitated, in Gandhi’s own view, by the historical conditions of modern society itself, in which politics and the state pervaded every aspect of life. When asked how he reconciled his “idealization” of samnyasa with his struggle for national independence or swaraj, Gandhi replied:

If the samnyasins (renouncers) of the old did not seem to bother their heads about the political life of society, it was because society was differently constructed. But politics, properly socalled, rule every detail of our lives today. We come in touch, that is to say, with the State on hundreds of occasions, whether we will or no. The State affects our moral being. A samnyasin, therefore, being well-wisher and servant par excellence of society, must concern himself with the relations of the people with the State, that is to say, he must show the way to attain swaraj. Thus conceived, swaraj is not a false goal for anyone . . . A samnyasin, having attained swaraj in his own person, is the fittest to show us the way. A samnyasin is in the world, but he is not of the world.73

In Gandhi’s view, then, in contrast to the past, when society had been autonomous in relation to the state, politics in the present was so all-pervasive and overpowering that nothing was allowed to remain exterior to it. The omnipotence of the state was accompanied, paradoxically, by a doctrine of political freedom that was grounded on the idea of the state and the discourse of rights and identity. It was imperative under these conditions to launch a struggle to retrieve the earlier discourse of renunciative freedom that had been colonized by political discourse, in parallel with the struggle to regain the autonomy of society from politics. The most appropriate leader for such a movement was clearly the samnyasin, who embodied that marginalized discourse of renunciative freedom. Indeed, insofar as the samnyasin was “in the world, but not of the world,” his presence in the movement, in Gandhi’s view,was a constant reminder that real freedom could not be achieved within politics. The renouncer, then, had a dual function: ethical service to society and ethical resistance to the state. He was to involve himself with politics on behalf of society against the state.

By emphasizing the discourse of renunciative freedom and the figure of the samnyasin as the leader of the movement, Gandhi, even as he launched a movement of opposition to the British, was also preempting the emergence in India of a modern Western discourse of freedom based on the state and identity. At stake was not just

independence from British rule but the imperative to foreclose the possibility of the emergence and dominance of a discourse of freedom that would be grounded in the nation-state as the all-powerful arbiter of the destiny of people and society, and its corollary the discourse of identity.

Discursive DIfference: Renunciative Freedom as Unity of Self and Other.

I

n a century torn apart by wars, violence, and genocide, the Gandhian movement against British colonial domination in India stands out as a unique experiment in political resistance: it was the first and also the largest mass resistance movement in the world based entirely on the idea and practice of nonviolence. The critical importance of nonviolence in the Gandhian movement came from its grounding in the Gandhian discourse of renunciative freedom in its difference from Western discourses of political identitarian freedom. The centrality of the notion of freedom to both Indic and Western cultures cannot be understated: while in Indic intellectual traditions the pursuit of renunciative freedom was historically regarded as the supreme goal, in the West the notion of political freedom had over time come to be recognized as its highest political and intellectual achievement. Indeed, it was as a place where the historical telos of political freedom came to find its fulfillment that the modern West presented itself as the ultimate measure and standard for other cultures and societies and their histories. Insofar as the Gandhian nonviolent revolution was grounded in a competing discourse of freedom, Britain, as the self-proclaimed agent of Western civilization, faced much more in India than just another anticolonial resistance movement against the empire: it faced a challenge to its core notion of political freedom.

It was one of the remarkable features of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century British liberalism that even as it held freedom to be the highest goal that a man or a society could aspire to, it was also the flag-bearer of British colonialism. British liberals saw no contradiction in fighting for democracy or self-government at home and for colonies abroad.74 For Gandhi, this reflected the essential nature of the Western discourse of political identitarian freedom, in which there was no contradiction between freedom of the self and domination over the other. In his view, it was precisely because this notion of political freedom was grounded in the idea of the self and identity in general that when faced with the other, it turned into an exercise in domination or power. Thus, power, the Gandhian movement demonstrated, was the underside of the Western discourse of freedom.

Remarkably, Hegel, the philosopher of “the end of history,” had foreseen—almost a century before the arrival of Gandhi—that the Indic discourse of renunciative freedom might turn its attention to the real world with the intention of changing it. Indeed, sure of his dialectical method, Hegel had even boldly predicted the nature and implications of this possibility were it to come to pass. When this abstract and negative freedom turns to actuality (the concrete world), he asserted in 1821, “it becomes in the realm of both politics and religion the fanaticism of destruction, demolishing the whole existing social order, eliminating all individuals regarded as suspect by a given order . . . Only in destroying something does this negative will (or freedom) have a feeling of its own existence . . . its actualization can only be the fury of destruction.”75 Contrary to Hegel’s predictions of “the fury of destruction,” however, the tradition of renunciative freedom introduced to the world a whole new kind of politics—the politics of nonviolence. If history proved Hegel’s prediction wrong in such a dramatic fashion, it was because he had encountered in the notion of renunciative freedom the exteriority of another tradition of thought whose logic escaped his all-encompassing dialectics.

In 1947, as news of the partition of India and a transfer of populations became public, large-scale riots between Hindus and Muslims began to break out in different parts of the country. While the members of the Indian National Congress were busy in Delhi celebrating independence and taking the reins of power, Gandhi spent his last days visiting one riot-prone area after another. It is said that through the moral power of his fasts for peace, he single-handedly brought much of the disorder to a spontaneous halt. When he was fasting in Calcutta, where the most devastating riots occurred, a Hindu man came to speak to him. He told Gandhi about his young son who had been killed by Muslim mobs, and about the depth of his anger and his longing for revenge. Gandhi is said to have replied: “If you really wish to overcome your pain, find a young boy, just as young as your son, a Muslim boy whose parents have been killed by Hindu mobs. Bring up that boy like you would your own son, but bring him up with the Muslim faith to which he was born. Only then will you find that you can heal your pain, your anger, and your longing for retribution.” The only way to overcome the cycle of revenge, in Gandhi’s view, was to reverse and thereby shatter the logic of identity. In the Gandhian frame of things, it was not the assertion of identity that would bring true freedom, but the loss of it. It is not surprising, then, that Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist whose idea of freedom based on national identity, nationalism, and the nation-state found itself in conflict with a Gandhian discourse of freedom that went beyond identity and state.