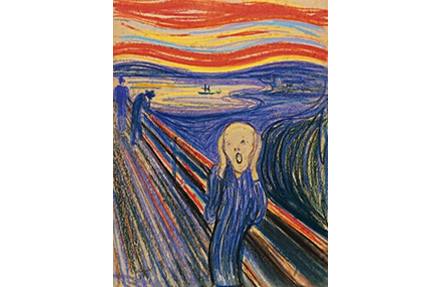

“The Scream” by Edvard Munch

Saitya Brata Das

I

“Harijan” as Idolatry and Concealment.

A

t certain historical moments when names too lofty for a phenomenon (names that conceal and manifest the phenomenon at the same time) have once more shown themselves to be decadent and demeaning, it becomes imperative to invent a new name. When names like ‘Harijan’, in their very loftiness and sublimity once more came to conceal the utterly lacerated existence of the untouchables in India, it was imperative to invent a new name ‘Dalit’.

Thus, the event of the name – the name ‘Dalit’ here – is born out of a paradox, and responds to this paradox: the too lofty name ‘Harijan’ is too demeaning and humiliating to indicate the humiliated condition of the oppressed ones! The sublime word or the name ‘Harijan’ – the people of God – does not reflect the scattered, bruised, wounded and lacerated condition of the untouchables; in a cunning way, this idolization masks the real, brutal condition of an epochal millennium-long suffering. The name here becomes idolatry.

The name ‘Dalit’, then, is intended to disclose the idolatry of all hegemonic oppression that the regime in force perpetuates. For reproduction of its domination, the hegemonic force never ceases producing and reproducing phantasms that emanate from idols: in the words of the French philosopher Louis Althusser, they ‘interpellate’ the whole ideological apparatus, and in this manner, mask its true character. The subjects, thus interpellated, then ‘interiorize’ the hegemonic domination which makes reproduction of domination easier and less coercive.

This explains how in a patriarchal society women can become the very agents of oppression against other women, and in a millennium long caste-based society, Dalits may accept the hegemonic domination as something ‘natural’ and ‘essential.’

What is non-natural is naturalized and essentialized, concealing the historical character of these phenomena, as if women are naturally and essentially inferior, as if Dalits are naturally and essentially inferior, socially as much as individually, morally as much as physically.

Names like ‘Harijan,’which are supposed to elevate the inhumane condition of the Dalits, end up producing phantasms; by taking away the flesh and blood from women, they are now turned into Goddesses, into fantastic figures which know not any human suffering of real flesh and blood of women.

What, then, is in a name can only be understood by posing the question: who is naming it? (Emphasis added)

I

n each act of naming by the hegemonic force, there is originary violence: it wants to exhaust the infinity of the phenomenon (the unspeakable and unnameable sufferings of the Dalits!) in the name. The name becomes a classifiable category in the administrative order of things which can be manipulated, managed, ordered by bureaucratic and political reason. The name, then, becomes an item that signifies a group of numbered people (and statistics of demographic census helps) which ends up becoming a ‘vote bank’ to fight for elections. The absolute and non-negotiable, the measureless and nameless sufferings of certain people are now reduced to a manipulable group which can be administered in sight of conditioned and negotiable rights through constitutional means.

The name conveniently forgets the whole absolute and unconditional demands of absolute justice. The very name, which is supposed to elevate the lacerated condition of a certain people, has become a mere political means of perpetual political hegemony of the dominant caste.

Therefore, it is absolutely imperative to inquire who is naming whom? There is violence in imposing a name, a cognitive violence, which is the ground of all possible political and administrative violence of the hegemonic power. The colonial power which came to India and ruled over us for more than a hundred years knew the power of the name. It does not have to be a linguistic name: a flag, an anthem, a symbol, a spectacle can do the same! The event of naming (a street, a library, a University, etc.) is, therefore, not neutral: when used by the hegemonic force, the name ‘Harijan’ becomes idolatry, a phantasm, a myth.

Thus, the name ‘Dalit’ became necessary at a certain historical moment in India. Sounding almost like an ‘onomatopoeia’, it is to evoke, not what is nameable, calculable and categorical but something like infinity of a bruised existence, unnameable and immeasurable, beyond all totality and totalizable historical experience that is subsumed under the gaze of administrative and political reason. Instead of fixing up the phenomenon called ‘untouchable’, the name ‘Dalit’ is intended to open up the whole world of naturalization and essentialization on whose basis the hegemonic force operates and legitimates itself.

Such a name ‘Dalit’ can, then, only be provisional: once the hegemonic force withers away, and social justice prevails, the name ‘Dalit’ too will wither away.

The name ‘Dalit’ does not, therefore, signify a natural entity, but an immense and measureless human suffering which is historically produced by the Brahminical order. As historical product, along with the withering away of the hegemonic force, the name too will wither away.

The subject of this withering cannot be the hegemonic force. From Hegel and Marx we know that the subject of radical historical transformation has never been and is never the hegemonic force, but the subject that is oppressed, wounded, scattered and bruised in human civilization. This is the privilege, not of the Brahminical order, but that of the Dalits: it is the Dalits and it is women who are the real subjects of radical transformation of human history.

B

y being the very ‘minus’ figures in human history, they bring about historical transformations which are incalculable and revolutionary. The hegemonic force, on other hand, suppresses such transformations, calling them back to the order which helps perpetuate their domination in turn.

What is, then, in a name? What is in the name ‘Dalit’? We can say: ‘everything’ and ‘nothing’. The name ‘Dalit’ does not mean anything particular (localizable, datable, manipulable and manageable entity in service of the administrative reason), but for that matter it is not mere nothing: it opens up the demand of absolute, non-negotiable and unconditional social justice that cannot be reduced to political-practical negotiations through constitutional means by winning elections.

In other words, it begs the immense question of the ethical that exceeds conditioned politics of negotiable demands and rights.

II

“Dalit”as evocation of lacerations.

I

t is imperative now to think the political at a different level than has been done so far, to think the political beyond strategies, negotiations, and playing cards (caste card, gender card, minority card etc.). This means that to demand justice in the name of a repressed caste or a gender in itself cannot be reduced to playing cards or doing politics at the level of strategies. This is precisely what is difficult to understand today. If the very idea of ‘politics’ is over-determined, or exhausted, in the strategic moves that we play in the realm of practical affairs to secure specific rights or conditioned profits, and thereby mobilise forces against forces, whether in the name of a specific caste or gender, then I am not primarily doing politics. What I may be said to be doing then, and also thinking and professing then, is something else and at another level, in another manner, and in another tongue.

Therefore, what I am, and the position I assume today, cannot be understood by the plethora of attributes thrown at me, whether by well-wishers or by those who accuse me of playing cards, caste politics, minority politics, whatever. They don’t understand what I am trying to do here.

I am not a ‘communist’ or ‘dalit’ — understood as an attribute or predicate which I strategically use to gain specific rights through negotiations with those in power. Rather, Dalit is the name through which the immense and immeasurable waves of injustice and savagery have swelled through the centuries and still swell; the name through which rises that clamour for an infinite, unconditional, and non-negotiable justice – and the specific rights to be secured in the domain of the political.

This fine distinction between ‘dalit’ as an attribute and Dalit as “the weak messianic power” (as in Walter Benjamin) is marked by an irreducible difference. This difference is completely erased when people discuss my thoughts, my actions and my political practices. I do introduce, in writing, and in my action in the political domain, a ‘philosophy’ of the political which consists of thinking that which infinitely exceeds, while passing through, the strategic politics of conditioned negotiations.

This philosophy of the political is not a storehouse of maxims or theorems which can be strategically put into practice by filling up their empty forms. It can’t be understood in the idiomatic gesture of regulative actions, as happens in Immanuel Kant’s understanding of moral actions. It consists instead, of introducing into the political the messianic intensity that does not exhaust itself in conditioned realisation of specific rights.

If one speaks of ‘proletariat’ now or of ‘Dalit’ – and it is necessary do so – it is only so that the proletariat destroys all other classes. And while destroying them, it too must pass away. So it is with the ‘Dalit’. The absence of the Dalit in just society is precisely the consummate messianic instance in the name of which all political struggles bearing the name “Dalit” must be carried out.

The name “Dalit” can be used today and must be used, but only as the name of the un-nameable. It is not a simple name. It evokes what remains; it will remain un-nameable until infinite justice arrives. Like a dying man who wants life, the oppressed clamour for justice. Our existence, in its very finitude, does not want to be exhausted in mere negotiations for conditioned-practical rights. Only infinity saturates and consummates our existence. This is why justice is the infinite idea par excellence.

W

e must speak out today; which means, precisely, risk our own existence. Yet this risk is also the very movement that goes beyond, by traversing the realm of death. S/he who does not speak knows no hope, for hope is the venturing beyond into the unknown. We must clearly distinguish between the officially recognised ‘promotion’ in the hierarchy of the academic institution and the true intellectual worth of a body of works that someone leaves behind.

Only those who work at the same intellectual and existential level as the scholar in question can really evaluate and appreciate the true worth of that form of life and that work. In the later sense, which is the true sense, I am ‘professor’ already. ‘Professor’ in the limited sense – in the hierarchy of the academic institution — is dubious at best. It is often mere reduplication of social hierarchy into the academic situation. It can be — as we all have eyes to see, unless one chooses keep her eyes closed – manipulated and abused by the technology of sheer quantification, by the political ideology that governs social relations, by millennium-long social injustice and prejudice. It is this prejudice and injustice that is the stake and that is the question. Here and now.

Saitya Brata Das teaches English Literature and Philosophy at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He has published peer-reviewed articles extensively, He co-edited (with Soumyabrata Choudhury) “The Weight of Violence: Religion, Language and Politics” published in 2015 by Oxford University Press. The second part of the essay is reprinted with permission of author from Indian Cultural Forum where it first appeared under the heading Who is the Dalit?(http://indianculturalforum.in/2017/06/18/who-is-the-dalit-saitya-brata-das/)

Leave a Reply