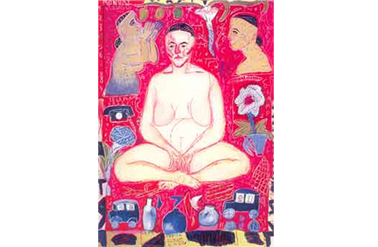

Arpita Singh: Red Feminine Tale. Acrylic on Acrylic sheet. 1995

Madhuri Sastry

If there is a beginning to this, it is probably the night that the Rarr Woman told me her story. You could, if you’re the sort of person that likes to visualize things, imagine her to be any woman. Someone with the face of the lady you saw while you were stuck in a traffic jam. Wavy brown hair, and big brown eyes to match. That girl who used to sit three rows away in your Economics class, so small and fragile. Every woman.

I

The Rarr Woman

T

he Rarr woman (RW for short) is in her late twenties. She moved to a new city a while ago, job contract signed, bank balance peachier than she could remember from her student days, the air thick with promise of independence. Her move turnedinto much more than a geographical shift: it was a social shift, a shift to a place where thoughts and values were different from hers.

Soon enough, RW met someone. Someone who didn’t fit the societal description of a perfect match.Far from it, in fact. You see, RW’s new boyfriend was some decades older than her. Her friends would tease her, “So what do we do when we meet him? Touch his feet to seek his blessings, or do a pranam?” All the while she was acutely aware of the very palpable discomfort with the idea of a romance between an older man and a younger woman. But RW laughed along, humouring them, patiently enduring the countless, seldom-creative iterations of this “joke”. RW was enveloped in the heady haze of a hopeless romantic in the early throes of a relationship.

A few months in, she missed a period. Every woman who has ever experienced this knows the all-consuming feeling of dread. She checked her calendar frantically, hoping for some miscalculation on her part. As days went by, RW knew she had to grit her teeth and do the inevitable – take a pregnancy test. And so she did, with her partner by her side, anxiously keeping time as they waited for the results.Positive. Once again, just to make sure. Two red lines on the stick.Positive again.

So RW went to the hospital.

Abortion is, to a degree, legal in India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, or “MTP,” governs the practice. The original purpose of the MTP wasto protect the health of the mother, and guarantee safe and legal abortions. To protect women from quacks.So, you can say there is a qualified “right” to an abortion in India—but how far does that right actually go? In truth, women face a number of roadblocks.

Thanks to patriarchy and misogyny, the question “married or unmarried?” is the gatekeeperto all sexual health related issues, including pregnancy. It decides how the woman will be treated – mentally, emotionally, and socially. In RW’s case, if the hospital folks found out that not only was she unmarried, but also that the “older guy” waiting outside was the father, all hell would have broken loose. A double whammy of un-Indianness.

The most pressing question, then,became whether to get it “taken care of” locally or to go to a city better equipped to cope with their “unconventional” relationship (read: where no one knew them). They settled on the local hospital; they both had to work and couldn’t afford to uproot their lives.

S

o RW walked into the nursing home to have her abortion, a strong, independent woman…with a hint of nervousness. She had always believed in a woman’s right to choose, the right to decide. Including, and especially, what she did with herbody. Sex before marriage was herchoice and she made it. The abortion was her choice too, and she made it. So,there she was, prepared, cloaked in thick skin and armed with an arsenal of witty comebacks, in case anyone took too many liberties with her.

“Pregnant hoon, doctor se milnahai”

RW was ushered into the gynaecologist’s office, alone. Her partner stayed back. Her “unmarried” status was problematic enough, and they didn’t need any more judgments or raised eyebrows.

RW was then taken for an ultrasound, in advance of her “procedure”. She took off her pants, and then her underwear, laying bare her vulva towards the nurse who was prepping her. But she didn’t feel naked and stripped until the doctor said, full of contempt “there are people who come to us who can’t bear children…and then there are people like you”. RW remained silent, ignoring the sharp sear of humiliation originating in the pit of her stomach, making its way up to her heart, causing it to beat a tattoo against her chest, and finally to her face, where it stained her cheeks red, and made her eyes well up. Her thick skin began to seem flimsy.

After the ignominy of the ultrasound, she was taken to have her pregnancy “enlisted”, so that it could be performed lawfully. To ensure safe and legal abortions, they are registered (enlisted) at whatever hospital, nursing home or clinic one goes to. A Central Medical Office monitors these cases, and does not allow multiple medical institutions to deal with the same abortion.

RW decided to use the “abortion pill”, instead of opting for an in-hospital procedure. The pill method – beginning with the pill-insertion, followed by an agonizing wait, unbearable pain, and more blood that she had ever seen in her life – lasted almost 15 days. These nurses who inserted the pill took on the role of unsolicited sex-life counsellors. Theirtone,and barrage of innuendo and snarky remarks made herwant to shrivel up. She finally deployed one of her comebacks, attempting to joke when one of them asked her whether the “uncle” sitting outside was the father. “Mine or the baby’s?”, she replied.

RW’s ordeal with the nursing home dragged through the 15-day period, and then the follow-up. There were times when she desperately wanted a new doctor, someone understanding, someone who didn’t make her feel dirty and undignified. But already registered with that hospital, she was stuck. She never felt safe, cared for, or understood. Her gynaecologist was reluctant to talk about safe sex, or really any sex at all, especially since it was pre-marital. Demeaning comments were tossed at her all too quickly. “When you get married, this abortion will not help. This will create complications for when you want to have your own kid.”

But RW had her abortion, and she hasn’t been the same since. “Not because of the abortion itself,” she told me, “but because of the ordeal surrounding it. I second-guessed myself so much, I don’t really know who I am anymore.”

II

The Rarr Woman

T

he Rarr Woman is one of millions. Abortions were illegal shortly after Indian independence, a vestige of the British Raj manifested in the Indian Penal Code from the 1800s. But with a wave of liberalization spreading across the West in the ‘60s, former colonies began to consider legalizing the practice. In 1966, the government appointed the Shah Commission to study the social, economic and legal aspects of abortion. The Commission’s report recommended legalizing abortions on compassionate and medical grounds, paving the way for the MTP Act. The emphasis was on public health (India was struggling with a population problem to boot), not a woman’s right to choose what happens to her body – the quintessential feminist perspective.

The act makes clear that abortions are a “qualified right”. They are permissible only if a medical practitioner concludes that having the baby would cause significant harm to the mental or physical health of the mother, or if there is a chance that the child will be born with physical or mental defects.Under these restrictions, abortion is legal for up to twelve weeks, or the first trimester. Women can terminate pregnancies resulting from rape or incest, and for socioeconomic reasons that render them incapable of raising a child. Women may seek to have an abortion for up to 20 weeks. She may also decide to terminate a pregnancy without the influence of her husband and family (except minors and women suffering from mental illnesses, both of whom require the consent of one guardian). Married women have it slightly better than single women or sex workers. If a married woman’s contraception fails, the law affords her a presumption of mental distress, freeing her from having to justify her abortion.

At first blush, these laws seem like they satisfactorily protect women, allowing them abortions in a variety of circumstances. However, they do not recognize women’s autonomy, their self-determination, and leave the ultimate decision up to the healthcare provider. Women are thus completely dependent on their physicians, and even find themselves having to justify intensely personal decisions to strangers, sometimes men.

Close to 50 years afterthe “legalization,”thanks to restrictions and stigmas put in place to “protect” women, unsafe and illegal “backdoor” abortions abound. In fact, estimates show that most abortions in India are still illegally performed. The Abortion Assessment Project estimates that of the 6.4 million abortions performed annually, 3.6 million or 56% are unsafe. Deaths from unsafe abortion are estimated to constitute 10%–13% of the total maternal deaths in India.

T

he reasons for this are three-pronged. First, there is little awareness about the MTP among non-urban women. Second, the MTP authorizes a small pool of healthcare practitioners to perform abortions. Middle and low-income women are often unable to bear the costs, and no more affordable alternatives exist, driving them to get unsafe abortions from quacks and back alley “doctors.” They are tied to the hospital their abortion was enlisted in, like the Rarr Woman. Women value confidentiality, and worry that they will get “found out” if they have an abortion at the only hospital in their vicinity authorized to perform them. Finally, the stigma for single women and sex workers, and the ultimate decision being placed in the hands of the physician have a chilling effect on women’s abilities to seek safe and legal abortions. Like RW, already vulnerable, they are criticized and shamed.

The courts have not been particularly progressive in this regard. While some courts have allowed abortions beyond 20-weeks in rare cases (usually rape or incest), the Supreme Court has a more disappointing track record. In February of this year, the Supreme Court refused to allowthe abortion of a woman 26-weeks pregnant with a foetus that would be born with Down syndrome. Acknowledging that the health of the child was in danger, the court nonetheless pronounced their inability to do anything due to the 24-week limit imposed by the law. A few months later, in May, the highest court once again denied anabortion to an HIV-positive woman, a victim of sexual assault, who was 26-weeks pregnant. In this case, they blamed the lengthy court battle for preventing her from getting the justice she deserved. As recently as this July, the Supreme Court once again denied an abortion, this time to a 10-year old girl, 28-weeks pregnant, raped by her uncle. Relying on her physicians, the court concluded that it would not be in her best results to allow the abortion. This little girl was left with two options:to induce labour, or allow the foetus to come to term and be delivered. Doctors and activists in the country were alarmed, worrying about the life-threatening complications involved in delivery for a young girl, physically undeveloped to birth a child.

C-Sections pose very serious risks to girls under 15. Pregnancy complications such as hemorrhaging, high blood pressure and obstructed labor were the leading cause of death among female adolescents in 2015, according to the WHO. On August 17th, two days after our seventieth Independence Day, this 10-year old rape victim had a C-section. She made it through. In a manner of speaking.Her parents have refused to even see her child, refusing to take custody, deciding to put it up for adoption instead.

III

The Way Forward: Freedom includes Reproductive Freedom

T

he core irony is that the MTP –even though enacted to ostensibly protect women–does not grant women the basic dignity of agency.It should be obvious, but women need to be in charge of their own bodies. Take, for example, the MTP’s absurd distinction between married and unmarried women: only married women benefit from the presumption that their contraceptive failure caused mental distress. Single women have to justify and provide explanations their decision to abort. By creating this farcical distinction, the MTP itself allows healthcare providers to be guided by their moral and social leanings, rather than their professional duties. All women have the right to freely decide the number and spacing of children. Single women, too.A law that elevates a woman’s social position – making her more or less independent – based on her marital status is little more than an extension of patriarchal control.

Alright, you may think, calm down. Surely it shouldn’t be difficult for unmarried women to get safe abortions by saying it would be damaging to their mental health. After all, she needn’t adduce any proof in this regard. No note from her shrink or therapist. Well-meaning gynaecologists must understand that.

Some do. I spoke to Dr. Manisha Risbud, an OBGYN and fertility consultant practicing in Pune, to get an idea of the state of affairs in practice. “’Grave injury to mental health’ is a vague term, which is what most of us will tick in the forms which we submit for single girls seeking abortions. It allows us, and our patients access to the procedure which I believe is a fundamental right to women’s health,” Dr. Risbud told me. “Most of my colleagues in urban settings (including myself) will treat the [unmarried] patient as a “case ” who needs a medical treatment and safe practices in reproductive health.”

But this is essentially the only safety net that single women seeking abortions have. While innovative for the seventies, the law ultimately places decisions about a woman’s body in someone else’s hands.

Notwithstandingsympathetic gynaecolgists like Dr.Risbud,millions of women, like the Rarr woman, are not so fortunate. Corroborating this, Dr.Risbud told me of instances of practitioners “who are sanctimonious, impose their moral beliefs, and even charge more fees [for unmarried women] as a ‘punishment’”. Think about that for a second. A literal TAX.A literal PENALTY.On unmarried women, seeking to exercise their agency with regard to their bodies.

A

dditionally, doctors and activists are urging law-makers to raise the 20-week ceiling to 24 weeks, taking stock of medical advancements that have made first-trimester abortions even safer and more precise. Modern technology detects foetal abnormalities beyond 20 weeks, and we need a law that incorporates these life-changing advancements.The MTP as it stands now is a BAD law. And like many bad laws, it has a chilling effect on the exercise of rights. Not least because it can force women to seek abortions from quacks, thereby negating the MTP’s original intention of protecting women from unsafe, illegal abortions. The focus needs to shift away from healthcare providers, and to women.

There are, of course, legitimate restrictions on the right to an abortion. Society also has a validinterest in protecting the life of an unborn child. But the solution is a balancing act, where a woman’s right is strongest in the first trimester, and that of the life of the unborn child is strongest in the third trimester. Notice that in this equation society’s interest in policing what a woman does with her body is nowhere evident. That interest makes her un-free, in essence, turns her captive to someone else’s opinions. That interest is not legitimate. (emphasis added)

An MTP Amendment draft bill was proposed in 2014, and contains a number of progressive changes. Most importantly, it embraces a feminist narrative, empowering all women with the right to choose up to twelve weeks, requiring no physician approval. It also expands the group of health care practitioners, enabling trained non-allopathic and mid-level practitioners to perform abortions. This means that women will have more options to consider, which is beneficial from an economic perspective too. This will empower married women as well, who often victims of sexual violence in their marriage.

In fact, about 43% of crimes reported by Indian women are acts of cruelty committed by their own families! While spousal consent is not necessary under the MTP, the right to choose combined with an increased base of healthcare providers authorized to perform abortions would empower married women by acknowledging their autonomy, helping cut down on stigma, and affording them access to safe abortions.

C

rucially, the amended Act does away with any distinctions between married and unmarried women. The changed lawscreate a presumption of injury to mental health in case of contraceptive failure for all women. Finally, it increases the gestational period from 20 to 24 weeks, and allows for abortions beyond this period in case foetal abnormalities are detected. We cannot afford anymore lengthy court battles. We cannot accept more 10-year old rape victims forced into C-Sections.

Here we are, seventy years after independence, with supposedly one of the most liberal constitutions in the world with oh so many rights to protect its citizens. Just how free are Indian women?India holds many unsavory distinctions. According to the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index, out of 142 countries, India ranks 134th for economic opportunities for women, and 141st for their health and survival. Second-last!

These are basic protections, and their absence is tremendously disempowering. It has allowed the long history of policing women’s bodies and controlling their agency. Women bear the brunt of the sex-before-marriage stigma. Stigmas for sex in general, in fact. Women frequently choose not to report assault and abuse, as they feel exposed and unsafe. Let’s blame her, she probably dressed like a slut anyway. Only recently has the two-finger test for rape been deemed unconstitutional (yes, that is as barbaric as it sounds). Marital rape is still not considered a crime. India is home to the world’s largest population of sexually abused children, according to the BBC. More than 10,000 children were raped in India in 2015, most of them by relatives or family friends. Are Bharat and India mutually exclusive? How long must women be caught in this dichotomy, reduced to ‘collateral damage’ in a country struggling with its identity?

Girls and women have been held hostage by a patriarchal society, that views them as objects of control. Not as complete individuals, with no agency, no real freedom.A philosophical shift in the MTP is a small, but crucial stepin the empowermentof women.It’s one way to recognize their autonomy, individuality, agency and control over their bodies. To free them.

"Madhuri Sastry is a lawyer by training. She holds LLMs from the London School of Economics, and New York University School of Law. Madhuri runs a feminist and gender blog, "www.thechicksandbalances.com".She is currently based in the United States." References: 1.Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 2.Draft Medical Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Bill 2014 3.Shweta Krishnan, MTP Abortion Bill 2014: Towards re-imagining abortion care 4.The New York Times, “India’s High Court Denies Abortion for 10-year-old girl” 5.The Wire, “India’s abortion laws need to change, and in the pro-choice direction” 6.The Diplomat, “India’s Abortion Epidemic” 7.The Indian Express, “Abortion Law Amendments on Hold” 8.The Washington Post, “Ten-year-old Indian rape victim gives birth after a court denies her request for an abortion

Leave a Reply